/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/3c/d43cf19e-f38c-405b-9c67-a7612cbf8cbd/fig4jswjianningfubox.jpg)

Among the more than 7,500 fragments from the Java Sea shipwreck that reside in Chicago ‘s Field Museum are corroded lumps of iron, exported from China for use as weapons or agricultural tools in Southeast Asia ; button-like weights used on merchants ’ scales ; barnacle goose encrusted chunks of aromatic resin and crumbling bone ; and thousands upon thousands of ceramic wares. Each ancient object has its own history and context, but it was a bantam dedication on matchless that helped researchers unlock the mystery behind this wreck—or so they thought .

Etched on only two ceramic containers, the words “ Jianning Fu ” gave the lidded box a specific birthplace. When anthropologist Lisa Niziolek first saw the writing in 2012, she realized that the city diagnose only existed in that form for a brief window of time : “ Fu ” designated Jianning as a Southern Song dynasty superior prefecture beginning in 1162. By 1278, the city had changed to Jianning Lu, a newfangled appellation bestowed by the invade Mongol drawing card, Kublai Khan. That seemed to fit absolutely with the shipwreck ’ s initial date of mid-to-late thirteenth hundred .

This, Niziolek thought, was the smoke gunman. “ At first I was all excited that we were looking at this light fourth dimension period, ” she recalls. “ We were thinking that it was fair within a couple years of that [ political ] transition. ” Narrowing down the shipwreck ’ south senesce to such a unretentive rate of dates might ’ ve indicated that this boat sailed during the uneasy transition years between the Song and Yuan dynasties .

But once she began conferring with colleagues in China and Japan about the types of ceramic she was seeing in the collection, she started having doubts. Tantalizing inscription aside, the early experts thought the ceramics more closely matched the style of earlier objects. Archaeologists who first assessed the wreck in the 1990s sent a one sample of resin for radiocarbon analysis, which provided the date range of 1215 to 1405. “ It can be said with some certainty that the ceramics cargo does not predate the thirteenth hundred, ” those researchers concluded.

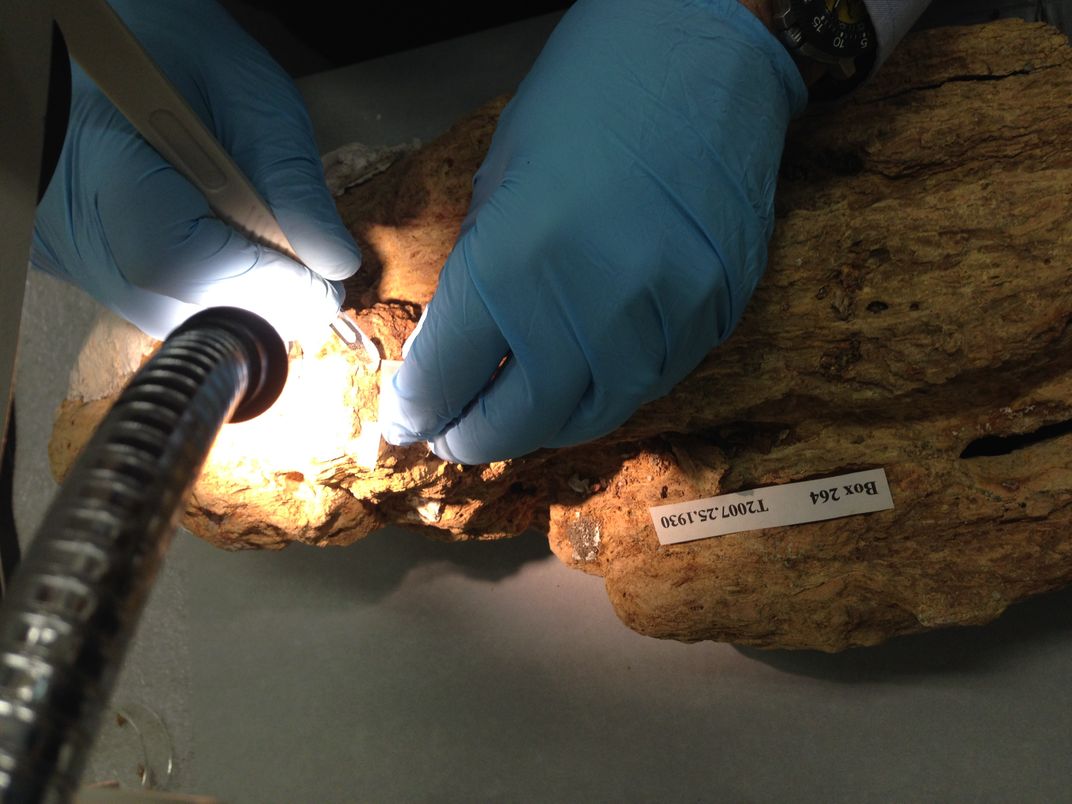

skill is about putting forth a hypothesis, comparing it to the available data, and adjusting it consequently. So Niziolek and her team decided to submit three more samples for radiocarbon analysis, two from the resin and one from the ivory. Thanks to technological advancements, labs now use accelerate bulk spectroscopy, a technique that requires smaller sample sizes and provides more accurate results than the earlier method acting, called radiometric date. The new results gave a significantly earlier date range : from 889 AD to 1261 AD, with the majority of the dates falling between the 11th and 12th centuries .

Those new results, along with a closer comparative psychoanalysis of the ceramic styles, were published Wednesday in the Journal of Archaeological Science : Reports. Given the newly data, it seemed that the inscription on the bottom of the ceramic box didn ’ t check the end of the Southern Song Dynasty—it was probably from the new dynasty ’ randomness get down. If that ’ second true, it gives researchers an important fresh starting charge to investigate objects from the shipwreck, from where those ceramics were made to which government oversaw the expanding Chinese deal net .

… ..

That there ’ mho anything to be studied at all from the Java Sea shipwreck is something of a miracle. The crash was discovered by fishermen, puff to the site by the birds feeding on swarms of pisces that lived in and around the debris, in the 1980s. At some point those fishermen began diving down to the wreckage, submerged below 85 feet of urine in the heavily trafficked Java Sea, confederacy of Singapore and near Borneo. In 1993 one of them sold the cognition of the shipwreck to a commercial salvage ship’s company, which began removing thousands of pieces from the locate. ( At the time, this character of action was legal under indonesian jurisprudence. )

In 1996, a new salvage company, Pacific Sea Resources, resumed retrieval of the objects, this time with the engagement of archaeologists and other experts. By this point, those experts estimated that of the 100,000 pieces of ceramics primitively on the boat, lone 12 percentage remained. They conducted a exhaustive discipline of the crash, using hunks of cast-iron to estimate the size of the ship—about 92 feet long and 26 feet wide. then, Pacific Sea Resources split the salvage items between the indonesian government and the Field Museum .

“ The objects could equitable as easily have been dispersed to auction houses and secret collectors, or looted and sold on the black marketplace, ” said Natali Pearson, a scholar at the University of Sydney Southeast Asia Centre who has studied other shipwrecks of the region, by e-mail. “ This places an inauspicious stress on objects of fiscal respect preferably than allowing us to think about the assembly in terms of its historic and archaeological value. With this in mind, studies such as this one are even more valuable. ”

Having physical remains is particularly significant here because the records left behind by chinese officials of the time can be selective in their concentrate. “ Those were written by people who went into government, so they ’ re going to look down at merchants, who were doing it for profit, ” says Gary Feinman, curator of Mesoamerican, Central American and East Asian Anthropology at the Field Museum and a co-author on the cogitation. “ They have a statist perspective, an elite position, and they don ’ t actually give full coverage to other aspects of life that may be there. ”

…..

not all researchers agree with the results of the new newspaper. “ The arguments on the basis of the inscription on the base of the ceramic and the results of AMS dating are not very strong, ” said John Miksic, a professor of Southeast asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, by electronic mail. Miksic worked on the shipwreck when it was first excavated in the 90s. He thinks the research hasn ’ metric ton proved that the original dates for the shipwreck indigence to be revised, adding that “ we do not have very many sites like the Java Sea shipwreck to go by, so our degree of confidence in the date of such sites does not have a bang-up share of comparative substantial for its footing. ”

That said, Miksic does agree that there ’ s enough to learn from continue analysis of the ship ’ south cargo. He hopes that at some steer more wrecks will be discovered and catalogued, and that a database might be created for comparison of such materials, including ceramics and the categorization of personal items that were on the transport .

Niziolek is already beginning to draw insights from the materials we have. Although we don ’ t know the identity or destiny of the merchants and sailors aboard the ship, we do know they transported their goods during a period of convulsion for China, and for Southeast Asia more broadly. The southerly Song dynasty, founded in 1127, came approximately as a result of the northern chunk of the country being lost to invaders. Around the lapp time, it became legal for chinese citizens to go abroad to trade ; previously, only extraneous merchants could come to Chinese port cities and sell products .

At this bespeak, goods moved across much of the world on a sort of maritime Silk Road ( Niziolek notes that although silk itself was likely on the Java Sea shipwreck, it wouldn ’ t have survived submerged 800 years, and by that compass point, ceramics made up the bulge of tradeable items ). China had trade relations with an estimated 50 countries. As one historian notes, “ by the Song time period, the scale of maritime trade had become so large that it may be deemed the first period of great oceanic trade wind in the history of the world. ”

The assortment of goods and the distance they came from is reflected in the artifacts housed by the Field Museum. Among the ceramics one finds everything from what Niziolek calls “ Ikea bowling ball ” —plain, mass-produced vessels—to flowery ewers with intricate molded decorations of a phoenix and flowers. then there are the unique pieces, which were probably the personal property of people on the embark : a shard of methamphetamine whose chemical recipe matches that of glassware from Egypt ; a crouch homo figurine that may have been the corner of a minor table ; bronze pieces that might once have topped the staffs of Buddhist monks .

…..

But there ’ s besides the issue of the material being dated. Both the ivory and the resin were submerged in water for 800 years, which degraded their condition. “ I would liked to have seen a date from the corked material from the coat to compare with the date from the inner material, ” said Joseph Lambert of the resin sent in for radiocarbon date. A professor of Chemistry at Trinity University, Lambert was involved in an earlier study on the resin, but not in this one .

Whatever their opinions may be on the probable date for the shipwreck, all the researchers agree on one thing : finds such as this are all excessively rare. The Java Sea has been an authoritative passage in trade routes for centuries. Thousands of shipwrecks litter the seafloor, from more than a thousand years ago to the World War II earned run average and beyond. unfortunately, besides many of those wrecks have been looted, or damaged in practices like blast fish .

“ While it is fantastic that we are in a position to conduct newfangled inquiry, my concerns going forward relate to the destiny of shipwrecks that are still in indonesian waters, ” Pearson says. “ Indonesia has modern legislation to legally protect subaqueous cultural inheritance, but—as the late end of WWII ships in the Java Sea demonstrates—Indonesia ’ s ability to physically protect wrecks remains limited. ”

Which makes this shipwreck all the more rare and valuable for researchers. Thanks to the fact that these objects belong to the Field Museum, researchers can continue analyzing them to learn more about this time period of asian trade wind. In one 2016 paper, Niziolek and others analyzed the chemistry of the resin to see where the blocks came from. In the future, they hope to extract ancient deoxyribonucleic acid from the elephant tusks to learn their origins, and analyze the sediments of large memory jars to see if they held foodstuffs like pickle vegetables or fish sauce. Some day, they besides plan to compare the chemical makeup of the ceramics to kiln sites in China to see where merchants purchased them .

evening after two decades above body of water, the shipwreck calm has dozens more stories to tell .

Recommended Videos