note : You may click on each image below to see a larger view .

The Atlantic migration of Europeans and Africans to America and the commercial activities associated with it created an economy that for the first meter in history could be called global. For many years, historians have relied upon the news commerce to capture this international world. Over the last decade, as research has focused more intently on ties between early mod consumers, producers, and distributors in America, Europe, and Africa, the concept of an Atlantic earth economic community has eclipsed the commerce paradigm. More recently, scholarly voices have cautioned against portraying the department of commerce of the Atlantic as a discriminate economic universe unto itself and ignoring the true globalism of trade in the time period. In discussing the evolving conceptualization of the early advanced economy, it is authoritative not lone to recognize the commercial increase that occurred during the time period, but besides to take into account the demographic and environmental changes that were consequences of that growth .

The mercantilist explanation for what kept the early mod economy running is quite aboveboard. The kingdoms of Spain, Portugal, Great Britain, and France american samoa well as the Dutch Republic each sought to accumulate wealth through advantageous overseas trade arrangements and colonies, while thwarting the ambitions of their rivals to do the same. America played the role of colony. When I use the term America hera, I do not good mean the thirteen colonies that bolted from the british Empire in 1776, but quite the entire Western hemisphere. For about all of the period under consideration, the area that became the U.S. had no freestanding identity. The thirteen colonies were neither the only colonies nor the only british colonies, and in the view of the remainder of the world, none of the thirteen were considered as the most crucial in the New World. That honor would credibly go to the sugar islands of the West Indies or, depending on the hundred, either the viceroyalty of Peru or New Spain, the chief sites of flatware mines. The scrappy, slave-trading, rum-running, smuggling-prone merchant communities that sprang up in towns like Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston might command focus on stage from the perspective of the national history of the U.S., but they contained just a small proportion of the hurl of thousands who developed new markets in America .

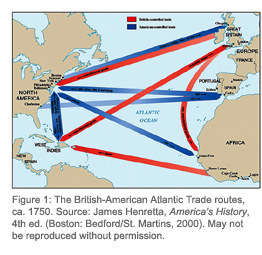

Though the mercantilist paradigm was a ball-shaped one, the most common visual image of it in U.S. history textbooks featured a map of Atlantic commerce. This map [ for an case see Figure 1 ] illustrated the “ trilateral Trade ” whereby eastern american colonies furnished crude materials, western Africa provided the parturiency force to produce the sensitive materials, and the imperial center, often referred to as the Mother Country, shipped manufactured goods to both. Historians pointed to inequities in this system as an significant lawsuit of the american Revolution .

Though the mercantilist paradigm was a ball-shaped one, the most common visual image of it in U.S. history textbooks featured a map of Atlantic commerce. This map [ for an case see Figure 1 ] illustrated the “ trilateral Trade ” whereby eastern american colonies furnished crude materials, western Africa provided the parturiency force to produce the sensitive materials, and the imperial center, often referred to as the Mother Country, shipped manufactured goods to both. Historians pointed to inequities in this system as an significant lawsuit of the american Revolution .

today, this schema has not therefore a lot been repudiated as re-interpreted. The most outstanding economic characteristic of the period remains the emergence in overseas commerce, but the term mercantilism is now used infrequently and the marketplace desires of individuals—especially on the consumption side—receive much greater credit for effecting exchange. Students are encouraged to think less about european empires struggling for manipulate of the major ocean lanes and colonial bases to achieve golden trading balances and more about the Atlantic as a meaningful economic entity where coastal inhabitants from all continents exchanged people and goods without constantly honoring imperial boundaries ( 1 ) .

To Atlantic scholars, it is not just a european or european transplant floor. transatlantic migrants were three times more likely to be from Africa than Europe during the menstruation ( 2 ), and as a consequence historians now have to take report of the strategies of African kingdoms and institutions in the draw of the slave trade ( 3 ). indian nations are not only relevant as providers of furs and skins and consumers of manufactures and alcohol but as the introducers of new agrarian commodities and, in some regions of America, a choice reservoir of undertaking and cultural identity. The doggedness with which colonists fixed their gaze across the Atlantic preferably than across the american continent may have less to do with their attachment to Europe and more to do with the ability of indian nations to contain colonial settlements to coastal areas, up until the latter eighteenth century .

The handiness of land and natural resources in America enabled the collection or production of a wide-eyed assortment of commodities—furs, lumber, collect, and pale yellow, for exercise. It was, however, the demand for two categories of goods that stands out as being most creditworthy for the continuing flow of capital, labor, and governmental military services across the Atlantic : groceries and silver medal .

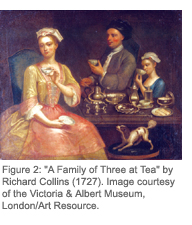

Contemporaries called the tropical dietary items that acted as energizers and appetite appeasers for the population on either side of the Atlantic and in Asia groceries. They included tobacco, carbohydrate, carbohydrate byproducts such as molasses and rummy, and caffeine drinks, namely tea, coffee, and cocoa. America became the premier web site for growing all of these crops except for tea and the enslave migrants from Africa became the prime cultivators. tobacco and the beans to make cocoa were autochthonal to America while others—coffee and sugar—were transferred over to take advantage of the low price of domain and the bound labor violence. Because many of these plantation commodities were thought of as luxuries—that is, not essential for human survival—their central role in the expansion of the earth economy has been often overlooked ( 4 ). That is a misconception, however. By the belated seventeenth hundred, the dutch and the English dominated the carrying deal over the Atlantic. 74 percentage of the value of imports coming into Amsterdam and more than 85 percentage coming into London from colonies in America consisted of tobacco and boodle products ( 5 ). Portraits, aristocratic and more middling class, as in the family shown hera [ see figure 2 ], often displayed the paraphernalia—tea service, porcelain tea cups, sugar bowl, clay pipes, snuff boxes—associated with the pulmonary tuberculosis of these tropical groceries. By the eighteenth century, the tug classes besides used these groceries on a regular basis ( 6 ) .

Contemporaries called the tropical dietary items that acted as energizers and appetite appeasers for the population on either side of the Atlantic and in Asia groceries. They included tobacco, carbohydrate, carbohydrate byproducts such as molasses and rummy, and caffeine drinks, namely tea, coffee, and cocoa. America became the premier web site for growing all of these crops except for tea and the enslave migrants from Africa became the prime cultivators. tobacco and the beans to make cocoa were autochthonal to America while others—coffee and sugar—were transferred over to take advantage of the low price of domain and the bound labor violence. Because many of these plantation commodities were thought of as luxuries—that is, not essential for human survival—their central role in the expansion of the earth economy has been often overlooked ( 4 ). That is a misconception, however. By the belated seventeenth hundred, the dutch and the English dominated the carrying deal over the Atlantic. 74 percentage of the value of imports coming into Amsterdam and more than 85 percentage coming into London from colonies in America consisted of tobacco and boodle products ( 5 ). Portraits, aristocratic and more middling class, as in the family shown hera [ see figure 2 ], often displayed the paraphernalia—tea service, porcelain tea cups, sugar bowl, clay pipes, snuff boxes—associated with the pulmonary tuberculosis of these tropical groceries. By the eighteenth century, the tug classes besides used these groceries on a regular basis ( 6 ) .

initially, westerly european governments gave little encouragement to the consumption of such commodities. In fact royal authorities frequently disparaged their product and habit, considering them either harmful or fiddling. rather, documentation for the commodities came from transatlantic merchant-planter alliances along with consumers living in nautical communities and urban centers. Once the revenues from the consequence duties began pouring into the treasury, however, the royals changed their minds. These apparently frivolous raw materials altered the dietary habits of the Atlantic community and ultimately the worldly concern. They were responsible for the spread of the plantation complex ( 7 ), a system of production that would become highly controversial in the nineteenth-century U.S. Taking a specific commodity such as tobacco and tracing the diffusion of pulmonary tuberculosis and the transformation in production and distribution to meet demand has emerged as an authoritative way to study Atlantic history in the early mod period .

even the way historians portray the relationship between the commercial system and the american english Revolution has been transformed by the Atlantic worldly concern border on. Americans reacted to the tax of boodle products, tea, and british manufactured goods, it has been argued, as consumers. Colonists from disparate provinces with divergent interests could all relate to problems connected to the pulmonary tuberculosis of the empire ‘s goods. Their mass pulmonary tuberculosis led to their multitude mobilization : resisting the Sugar, Stamp, and Townshend Acts, boycotting tea, pledging nonimportation, and ultimately declaring independence ( 8 ). Rather than viewing the american Revolution as the point at which the colonies threw off mercantilism and embraced economic liberalism ( 9 ), students are immediately encouraged to regard the market principles of need and supply as representing the colonial condition quo. The colonists, in this tell of the story, mobilized in order to halt any heavy handed imperial state interfering that would turn back the clock .

The Atlantic earth concept has much to recommend it as a manner to understand the global economy in which the U.S. came to be a dominant musician. The Atlantic as the supplier of population for America can not be denied. migration from other parts of the ball during these years amounted to small more than a trickle. The dramatic transformation of Atlantic commerce is besides obvious. For thousands of years prior to the mid-fifteenth century, existing testify suggests that nothing ventured far out into the Atlantic aside from a few Viking expeditions and periodic fishing vessels, while in the following three hundred years global commerce came to be directed and conducted from nations and cities bordering that ocean. And so it remained until the subsequently twentieth century when the emergence of the Pacific Rim, the European Union, and NAFTA suggest that a realignment is now taking station ( 10 ) .

Where the Atlantic global substitution class falls short, in the view of some scholars, is in its poor people integration of Asia, home to two-thirds of the worldly concern ‘s population, into the early modern network of deal. They argue that western Europe and flush parts of the Americas and Africa had relationships with Asia that were as or more authoritative than their relationships with one another ( 11 ). The choice then is whether we should think in terms of two freestanding worlds operating in this period, the asian world and the demographically much smaller Atlantic world of which America was a share, or whether we should consider the east-west connection meaning adequate to argue for a in full integrated global economy .

Those arguing the latter position would point out that capturing the East indian and chinese marketplace loomed much larger in the minds of Europeans than anything having to do with America or Africa and that America owed its “ discovery ” to that preoccupancy. Columbus ‘s and his sponsors ‘ stated determination was not the discovery of a New World but a northwest passage to the “ Indies, ” by which they meant East Asia. Just as the foremost portuguese attempts to sail around Africa had been sparked by the hope to establish trade with India, about the only reason for undertaking voyages to the Americas, until Cortes defeated the Aztecs in 1519, was to find East Asia. even after Cortes ‘s conquest, which led to an inflow of sword wielding military adventurers seeking protection, a northwest passage undertaking proved much more attractive to merchant investors than any military expedition. The photograph changed once again, however, with the discovery of rich silver mines in America. Silver is the other major product that most directly linked America with the global economy and, in terms of chronology, it came before the groceries associated with the plantation complex .

The old histories of mercantilism centered their fib on the infusion of spanish empire silver and gold, the rampant inflation in Europe it produced, and its function in the underdevelopment of Spain and its colonies. The newfangled adaptation of this narrative considers inflation less of a trouble and concentrates on the enormity of taiwanese demand for silver, which was needed both to expand its monetary system and to manufacture silver wares. Its willingness to offer advantageous terms of trade for those sought commodities created a ball-shaped commercial net in which America and Africa supplied the bullion and foodstuffs to pay for asian commodities distributed largely in european ships ( 12 ) .

The old histories of mercantilism centered their fib on the infusion of spanish empire silver and gold, the rampant inflation in Europe it produced, and its function in the underdevelopment of Spain and its colonies. The newfangled adaptation of this narrative considers inflation less of a trouble and concentrates on the enormity of taiwanese demand for silver, which was needed both to expand its monetary system and to manufacture silver wares. Its willingness to offer advantageous terms of trade for those sought commodities created a ball-shaped commercial net in which America and Africa supplied the bullion and foodstuffs to pay for asian commodities distributed largely in european ships ( 12 ) .

It was the mining of valued metals that kept european kings and commoners matter to in the Americas during that awkward half century or then between the last conquistadors and the first big boom in sugar and tobacco cultivation that ushered in the american plantation complex. not until the discovery of silver at Potosi in the peruvian vice-royalty during the 1540s did the spanish Crown, as distinct from secret adventurers and religious orders, make a committedness to govern America directly. Forcing Indians to extract the valuable ore [ see a contemporary ‘s depicting of the Potosi community in Figure 3 ], every year the Spaniards shipped over 50 tons of ash grey abroad. They sent it across the Atlantic where their european creditors used it in the chinese craft or they transported it across the Pacific to Manila, Spain ‘s east asian entrepôt. Why in the 1570s did Sir Francis Drake, the celebrated Elizabethan privateer, speculation into the Pacific and circumnavigate the globe ? Pure love of gamble ? Or could the mines of Peru have had something to do with it ? Without the bait of these Atlantic and Pacific fleets full of bullion most english, french, and Dutch exploration and colonization expeditions would never have materialized .

western european nations granted monopolies to trading companies, the boastfully businesses of the day, to compete for asian commodities. Some were dietary products like chinese tea and spices from what is now known as Indonesia, but others were manufactured goods such as taiwanese porcelain and silk and indian cotton fabric ( 13 ). All of these goods became wildly popular in Europe and America. In fact, in 1720 the british government forbade the import of cotton fabric because it weakened demand for alight woolens, their major industrial product. The Chinese refused to allow western european trade companies to establish permanent facilities in their port cities, so westerly Europeans, first the Portuguese and then a wider international community, built a commercial center at Macao on the west banks of the Pearl, the river which leads to the chinese port of Canton. [ number 4 indicates the size of the European enclave. ] not until late in the nineteenth hundred did Hong Kong, on the east side of the Pearl River, overtake Macao. Both cities remained under the control of western Europeans until the end of the twentieth hundred. Manila, the spanish entrepôt, besides spent most of its history as a colony. in the first place, however, these outposts had been set up because it was the entirely direction westerners could obtain taiwanese products .

western european nations granted monopolies to trading companies, the boastfully businesses of the day, to compete for asian commodities. Some were dietary products like chinese tea and spices from what is now known as Indonesia, but others were manufactured goods such as taiwanese porcelain and silk and indian cotton fabric ( 13 ). All of these goods became wildly popular in Europe and America. In fact, in 1720 the british government forbade the import of cotton fabric because it weakened demand for alight woolens, their major industrial product. The Chinese refused to allow western european trade companies to establish permanent facilities in their port cities, so westerly Europeans, first the Portuguese and then a wider international community, built a commercial center at Macao on the west banks of the Pearl, the river which leads to the chinese port of Canton. [ number 4 indicates the size of the European enclave. ] not until late in the nineteenth hundred did Hong Kong, on the east side of the Pearl River, overtake Macao. Both cities remained under the control of western Europeans until the end of the twentieth hundred. Manila, the spanish entrepôt, besides spent most of its history as a colony. in the first place, however, these outposts had been set up because it was the entirely direction westerners could obtain taiwanese products .

Consumer demand for East indian commodities grew over the course of the eighteenth hundred. In an important passing from the past and one that foreshadowed nineteenth-century developments, Europeans learned how to mass produce “ knock-offs ” of east and south asian fabric, furniture, and pottery. It was the manufacture of Indian-like cotton fabric in Britain that launched the Industrial Revolution. After independence, as the american merchant residential district regrouped, those on the Atlantic seaside began competing with their former partners for the lucrative China craft and manufacturing “ knock-offs ” of their own. Using Hawaii as an entrepôt, the U.S. besides expanded Pacific commerce ( 14 ). By 1800 it was Britain ‘s biggest rival in the China trade and late in cotton fabric fabricate ( 15 ) .

The three unlike approaches to understanding the place of pre-1800 America in the external economy each have their strengths and weaknesses. The commerce paradigm, emphasizing as it does imperial rivalries, is global in telescope but relies about entirely on the machinations of european royal governments to explain commercial expansion and colonization. The proponents of the Atlantic global scene assert that the use of said ocean as a highway for migrants, capital, and commodities represented the period ‘s biggest deepen in global trade patterns and that consumer demand of the societies bordering the ocean had much to do with that exchange. Assuming, however, that a collected commercial system existed within the boundaries of that ocean, critics contend, means leaving out more than two-thirds of the consumers of the land, including those in China, India, and southeast Asia, producers of some of the earth ‘s most sought commodities. Better integration of such important elements as the ash grey trade to China, the smash in indian cotton textiles, and the commercial history of the settlements and islands of the Pacific is a job presently afoot, even if the claim importance of each of these elements in the overall picture has however to be ascertained .

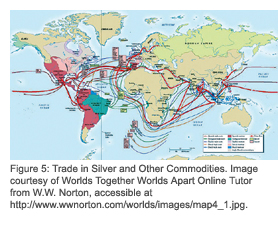

careless of the approach, it seems clear that the economic order that took shape after the european discovery of America redistributed unprecedented numbers of people to satisfy a growing global demand for its resources and products that in turn kept more tug and capital menstruate in to the alleged new world. oversea trade has been identified as the leading sector in economic emergence during this period. evening in well established european nations, emergence depended primarily on the expansion of the oversea trade sector ( 16 ). A major impulse for the adoption of the U.S. Constitution was the impression that survival as a state depended on overseas commerce and that its success required a solid central government. [ See Figure 5 for a map that identifies some of the major global trade routes of the eighteenth hundred. ]

careless of the approach, it seems clear that the economic order that took shape after the european discovery of America redistributed unprecedented numbers of people to satisfy a growing global demand for its resources and products that in turn kept more tug and capital menstruate in to the alleged new world. oversea trade has been identified as the leading sector in economic emergence during this period. evening in well established european nations, emergence depended primarily on the expansion of the oversea trade sector ( 16 ). A major impulse for the adoption of the U.S. Constitution was the impression that survival as a state depended on overseas commerce and that its success required a solid central government. [ See Figure 5 for a map that identifies some of the major global trade routes of the eighteenth hundred. ]

Read more: Maritime on Audiotree Live (Full Session)

If the origins of global economic growth are linked to this global department of commerce, other forms of growth that have been associated with the discovery of America appear to be more baffling. The ample Atlantic migration proved black for the autochthonal population, chiefly because of its susceptibility to new diseases brought by invaders or simply merchants who did no more than deal from their glide vessels anchored offshore ( 17 ). Despite the stagger losses of indian life in the Americas, the demographic phonograph record suggests emergence in ball-shaped population from the time of discovery forth. At first, as table 1 shows, the rise was humble and, although the detail here is not sufficient to indicate it, population numbers are believed to have stalled in the seventeenth century. Over the course of the eighteenth hundred, however, world population is estimated to have jumped by 50 percentage, the slope slanting up ever more steeply thereafter and continuing its dramatic ascent through the twentieth century .

In the Americas, succeeding generations of Atlantic migrants and their descendants enjoyed high gear richness rates in their new low density environment. concurrently, Europe ‘s population, despite the emigration, began to climb, as did China ‘s. Some of this “ old worldly concern ” growth has been attributed to the transfer of “ new world ” foodstuffs such as potatoes, dessert potatoes, peanuts, and corn ( corn ) american samoa well as american sales of pale yellow and rice in european markets ( 18 ). While in North America the bounty in foodstuffs and the accompanying high richness never produced a malthusian reaction, in certain parts of nineteenth-century Europe and in China it finally did. The dense population put greater press on natural resources. The environmental repercussions of the homo species spreading into previously uninhabited parts of the earth is a intrigue subject that deserves a big deal more attention. nowhere might the probe be more worthwhile than in America during the period under consideration here .

In the Americas, succeeding generations of Atlantic migrants and their descendants enjoyed high gear richness rates in their new low density environment. concurrently, Europe ‘s population, despite the emigration, began to climb, as did China ‘s. Some of this “ old worldly concern ” growth has been attributed to the transfer of “ new world ” foodstuffs such as potatoes, dessert potatoes, peanuts, and corn ( corn ) american samoa well as american sales of pale yellow and rice in european markets ( 18 ). While in North America the bounty in foodstuffs and the accompanying high richness never produced a malthusian reaction, in certain parts of nineteenth-century Europe and in China it finally did. The dense population put greater press on natural resources. The environmental repercussions of the homo species spreading into previously uninhabited parts of the earth is a intrigue subject that deserves a big deal more attention. nowhere might the probe be more worthwhile than in America during the period under consideration here .

Endnotes

1. The April 2004 issue [ volume 18 no. 3 ] of the OAH Magazine of History, entitled “ The Atlantic World ” and edited by Alison Games, takes this approach and focuses on three themes in the Atlantic : disease, commodities, and migration. The issue contains references to the many books and articles that have been written on early modern Atlantic communities in the past two decades .

2. James Horn and Philip D. Morgan, “ Settlers and Slaves : european and african Migrations to early Modern British America, ” Elizabeth Mancke and Carole Shammas, eds., Creation of the british Atlantic World ( Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, forthcoming ) .

3. John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, 2nd erectile dysfunction. ( New York : Cambridge University Press, 1998 ) .

4. Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World System : capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the european World-Economy in the one-sixteenth Century ( New York : academic Press, 1974 ), 41-42 .

5. Victor Enthoven, “ An appraisal of Dutch Transatlantic Commerce, 1585-1817, ” Riches from Atlantic Commerce : Dutch Transatlantic Trade and Shipping, 1585-1817, edited by Johannes Postma and Victor Enthoven ( Leiden : Brill, 2003 ), 438 ; Nuala Zahedieh, “ overseas expansion and Trade in the Seventeenth Century, ” in Nicholas Canny, ed., Oxford History of the british empire : Origins of Empire ( Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1998 ), 410 .

6. Carole Shammas, The Preindustrial Consumer in England and America ( Oxford : Clarendon Press of Oxford University Press, 1990 ) .

7. Philip D. Curtin, The Rise and Fall of the Plantation Complex : Essays in Atlantic History ( New York : Cambridge University Press, revised erectile dysfunction. 1998 ). Sidney Mintz recounts this work in Sweetness and Power : The place of Sugar in Modern History ( New York : Viking Press, 1985 ) .

8. T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution : How Consumer Politics Shaped american Independence ( New York : Oxford University Press, 2004 ) .

9. economic liberalism is used here in its nineteenth-century sense of belief in grocery store forces of demand and add preferably than governmental policies directing production and consumption .

10. The former twentieth hundred witnessed a significant geographic shift of populace craft towards the Pacific Rim .

11. Peter A. Coclanis, “ Drang Nach Osten : Bernard Bailyn, the World-Island, and the Idea of Atlantic History, ” Journal of World History 13 ( 2002 ) : 169-182 .

12. Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Giraldez, “ Cycles of Silver : global Economic Unity through the Mid-Eighteenth Century, ” Journal of World History 13 ( 2002 ) : 391-428, and Enthoven, “ An assessment of Dutch Transatlantic commerce, ” 435-6 refer to the Dutch use of american english silver for East Indies trade wind .

13. John E. Wills, Jr., “ european consumption and asian production in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, ” in John Brewer and Roy Porter eds. consumption and the World of Goods ( London : Routledge, 1993 ), 133-47 .

14. David Igler, “ Diseased Goods : ball-shaped Exchanges in the Eastern Pacific Basin, 1770-1850, ” American Historical Review 109 ( 2004 ) : 693-719 .

15. See the statistics in Louis Dermigny, La Chine et L’Occident : Le Commerce a Canton astronomical unit XVIIIe Siecle 1719-1833 tome II ( Paris : S.E.V.P.E.N., 1964 ), 521-528, 532, 539, 735, and 744 that show the setting of America ‘s entrance into the tea barter from the 1780s on and besides its add of silver and cotton .

16. Robert C. Allen, “ advancement and poverty in early Modern Europe, ” Economic History Review 56 ( 2003 ) : 431 ; Kevin H. O’Rourke and Jeffrey G. Williamson, “ After Columbus : Explaining Europe ‘s Overseas Trade Boom, 1500-1800, ” Journal of Economic History 62 ( 2002 ) : 417-62. The latter article asks a count of dear questions about the reasons for the smash in trade but lacks the tell to prove its cardinal competition that ecstasy costs did not decline over the three hundred class menstruation .

17. Igler, “ Diseased Goods. ”

18. Flynn and Giraldez, “ Cycles of Silver, ” concerning the effects of the transportation of corn, sugared potatoes, and peanuts over the Pacific .

I would like to thank the OAH/AP referees, and my colleagues John E. Wills Jr., Ayse Rorlich, and Darryl Holter for their comments and aid in writing this try .

Bibliographical Note

classical treatments of the emergence of ball-shaped deal include J. H. Parry ‘s beautifully succinct The establishment of the European Hegemony 1415-1715 : Trade and Exploration in the Age of the Renaissance ( New York : Harper and Row, Torchbook ed., 1961 ), Immanuel Wallerstein ‘s three comprehensive volumes on the modern world-system, The mod World-System : capitalistic Agriculture and the Origins of the european World-Economy in the one-sixteenth Century ; The Modern World-System II : mercantilism and the Consolidation of the european World-Economy, 1600-1750 ; and The Modern World-System III, The Second Era of Great Expansion of the Capitalist World-Economy, 1730-1840s ( New York : academic Press, 1974-1989 ), and Fernand Braudel ‘s autocratic refinement and Capitalism III : The Perspective of the World, tr. xian Reynolds ( Berkeley : University of California Press, 1992, orig. public house. in french 1979 ) .

The OAH Magazine of History 18 ( April 2004 ) publish edited by Alison Games is an excellent usher to the ever-growing literature on the Atlantic World approach peculiarly as it relates to the area that became the United States. The Atlantic Seminar at Harvard University maintains a web site, hypertext transfer protocol : //www.fas.harvard.edu/~histecon/visualizing/atlantic-history/, that features recent research in the field and has links to early sites of pastime. In addition to the Thornton ledger on the African Atlantic cited above, the existing ship manifests recording the african migration across the Atlantic are immediately available for sketch on CD, David Eltis et aluminum. The Transatlantic Slave Trade : A Database on CD-Rom ( New York : Cambridge University Press, 1999 ). The most exhaustive examination of transatlantic commerce is for Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Huguette Chaunu and Pierre Chaunu, Seville et l’Atlantique ( 1504-1640 ) 8 vols. ( Paris : Colin, 1955-1959 ). The phenomenonal arise in consumer demand for groceries and the growth of the grove complex is documented in Curtin, Mintz, Enthoven, Zahedieh, and Shammas mentioned above. For those seeking a regional breakdown of anglo-american craft, see John J. McCusker and Russell R. Menard, The Economy of British America 1607-1789 ( Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2nd erectile dysfunction. 1991 ). Breen ‘s ledger, above, relates the american Revolution to the Atlantic deal boom.

Read more: Maritime on Audiotree Live (Full Session)

The need to take a global rather than an Atlantic world position, as expressed in Coclanis ‘ test cited above, comes largely from studying the exploit on monetary flows, asian commerce, and the Pacific Rim. Dennis O. Flynn, in the article he co-author above and in a series of early books and articles, has made the strongest event that the demand for eloquent in China created an integrated global economy both Atlantic and Pacific. In addition to the works on chinese commerce and products by Dermigny and Wills cited above, a numeral of volumes have recently appeared confirming the size, tempt, and sophism of Chinese, Indian, and southeasterly asian production during the period 1500 to 1800. Coclanis ‘ essay cites many of them. Kenneth Pomeranz and Steven Topik, The World that Trade Created : society, Culture, and the World economy : 1400 to the Present ( Armonk, NY : M.E. Sharpe, 1999 ) is designed for a general consultation that picks up on that subject among others .

Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, Atlas of World Population History ( New York : Penguin, 1978 ) remains the best reservoir for populace population figures. The USC-Huntington Library Institute for Early Modern Studies has a new web site hypertext transfer protocol : //dornsife.usc.edu/emsi which offers on-line bibliographies with a global position on specific topics. last, hypertext transfer protocol : //networks.h-net.org/ is the world wide web address for H-Net which features numerous networks for different fields in history, among them h-world and h-atlantic. These networks offer teach resources, discussions, and reviews .

Carole Shammas holds the John R. Hubbard Chair in History at the University of Southern California. Her most recent book is A history of Household Government in America ( 2002 ) .