Introduction

seventeen days prior to the accidental obstruction of the Suez Canal on 23 March 2021 by the super container Ever Given, a french aircraft carrier strike group had passed through the duct on its way to the indian Ocean ( 1 ). It does not take an active imagination to think what could have transpired had these naval forces become trapped in the Suez Canal following a hostile work on their navigation systems. It is only possible to envision such scenarios because nautical security is increasingly beset by geopolitical tensions. We know that the European Union is heavy dependent on maritime trade routes for ability projection and its economic prosperity — 75 % of goods entering Europe do then by sea nowadays and Europe ’ sulfur navies and shipping firms rely on complimentary navigation. however, China ’ s naval expansion in the Indo-Pacific, Russia ’ s naval bearing in the High North and the Baltic, Black and Mediterranean Seas and Turkey ’ second hostile nautical acts in the eastern Mediterranean call into question the relative freedoms Europeans have enjoyed at ocean for decades .

Of course, it remains to be seen whether the EU can generate a greater maritime presence in such a context. The Union has accrued experience in deploying naval operations, undertaking boundary line and coastguard functions, performing nautical guard tasks, countering piracy and conducting nautical surveillance assignments. More recently, the EU has even established new nautical initiatives such as the Coordinated Maritime Presence ( CMP ) concept, which is designed to enhance maritime security in flimsy areas such as the Gulf of Guinea. EU extremity states such as France, Germany and the Netherlands have besides invested in national strategies and guidelines for nautical betrothal in the Indo-Pacific, and the EU will follow suit by the end of 2021 with its own scheme. A new EU Arctic strategy will be released in October 2021. NATO is besides about to revise its own Strategic Concept, which will undoubtedly focus on nautical issues excessively .

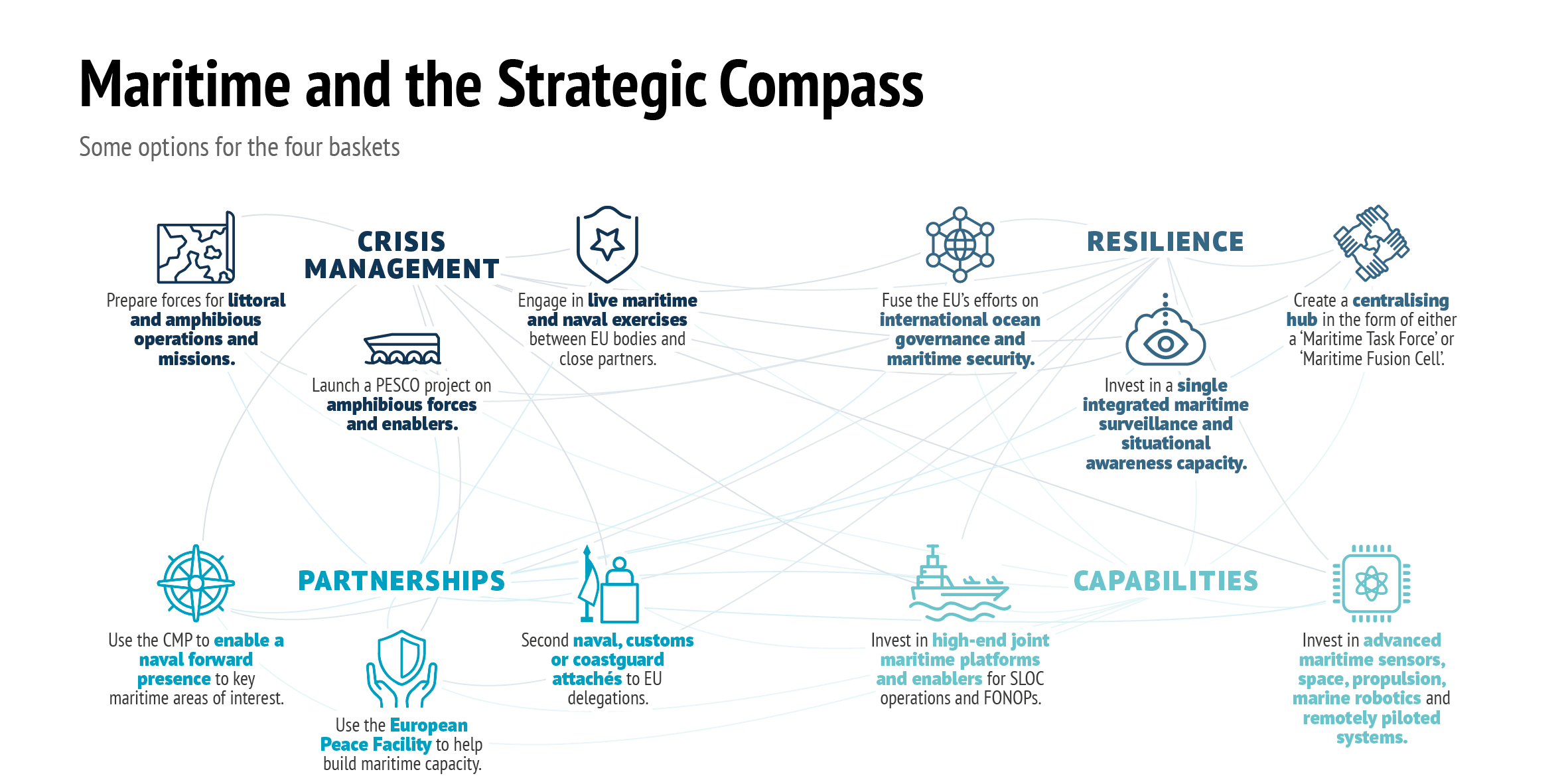

At the same prison term, by March 2022, the EU will present a Strategic Compass for security and defense, which is in part supposed to provide clearer steering on what type of nautical actor the Union should become. This is a ambitious job. There is limited political agreement on the Union ’ s nautical security function, and there is uncertainty about how far the EU should geographically extend itself when it has concerns closer to home. There is besides the doubt of limited european naval capabilities. Tackling these issues, this Brief asks how the Strategic Compass can make a tangible dispute to the Union ’ south function as a maritime security provider. Our first port of call, however, is to better understand the contemporary nature of nautical threats, risks and challenges .

Hard and fast? The changing nature of maritime security

Europe ’ randomness navies are increasingly being called upon to perform nautical security tasks. Violent piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has been met with enhance naval watchfulness in the area, insecurity in the Strait of Hormuz has resulted in a european nautical awareness inaugural ( EMASOH ) and longstanding crises in Libya and the Horn of Africa have required the deployment of EU naval forces in the human body of Operations Irini and Atalanta. On circus tent of this, countries such as France, Germany and the Netherlands have deployed or plan to deploy naval forces to the indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Germany will deploy its frigate Bayern in the second half of 2021 ( 2 ) and France initiated ‘ Mission Marianne ’ — consisting of a defend vessel and nuclear attack submarine — to the Pacific at the start of 2021 ( 3 ). Although many of these initiatives have been given impetus because of the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific, it is important to note the geographic extent of Europe ’ s nautical ambitions and the ( direct/indirect ) proximity of nautical threats, risks and challenges.

There is a security and economic rationale for enhancing the Union ’ s maritime presence .

These enhanced european nautical security initiatives have given rise to questions about what function naval power should play within the Strategic Compass. One can understand why, specially given a growing european recognition that freedom of seafaring and the external jurisprudence of the ocean are steadily being eroded. Some EU extremity states are directly implicated in this challenge, and it is deserving recalling that Denmark, France and Portugal have some of the largest exclusive Economic Zones ( EEZs ) in the world when calculated in km2. however, free and procure seas and oceans are in the interests of all EU penis states as they provide the basis for Europe ’ s economic prosperity — see that Europe is home to 329 key seaports ( 4 ). There is a security system and economic rationale for enhancing the Union ’ s maritime bearing. even nautical insurers are increasingly taking into consideration security system and geopolitical considerations when insuring shipping companies, vessels and ports ( 5 ). Regardless of whether a extremity department of state is landlocked or not, every EU member department of state feels the effect of maritime provide disruptions. For exemplar, Covid-19 led to an immediate 4.1 % decrease in ball-shaped maritime trade in 2020 in addition to disrupting provide chains, shipping networks and ports. ( 6 ) Yet it is not barely pandemics and duct blockages that threaten nautical trade. Increasingly, climate change will transform maritime spaces. For exemplar, if climate adaptation and coastal protection efforts fail by 2100 approximately 48 % of the world ’ second land area, 52 % of the global population and 46 % of global socio-economic infrastructures and activities are at risk of flooding ( 7 ). coastal areas in the EU and beyond are the most at risk from climate change. For the EU, this means that critical infrastructure such as ports, harbours and naval bases will be vulnerable and there could be resource depletion because of environmental risks. What is more, climate change could lead to the collapse of fishing stocks ascribable to water calefacient, which in act may lead to conflict between states and fishing companies, and new ship lanes are probably to open up in the summer season in the Arctic. Increasingly, climate change could aggravate transboundary nautical disputes, particularly where nautical conservation spaces or resources overlap with contested EEZs. ultimately, the increased use of renewable marine energy installations and connectors may replicate well-known infrastructure vulnerabilities at sea ( 8 ) .

China is a growing geopolitical nautical rival that can not be overlooked .

The oceans and seas are not then only conduits for nautical trade : they are besides home to food sources, critical critical infrastructure and strategic economic inputs. For example, consider that the Sea-Me-We-5 submarine telecommunication cable routes through six separate maritime zones such as the Mediterranean Sea and the Malacca Strait and has 18 different landing points including France, Italy, Myanmar, Oman and Singapore ( 9 ). Subsea energy pipelines and offshore installations are besides vulnerable nautical infrastructures — the EU imports gas and oil through the Mediterranean, Baltic and North Seas. Furthermore, critical sensitive materials that are substantive for the european economy are located far beyond EU shores and this includes magnesium from China, palladium from Russia, ruthenium from South Africa and niobium from Brazil ( 10 ). criminal networks besides operate across multiple seas and oceans. Safeguarding ocean lines of communication ( SLOC ) will therefore be another key undertaking for the Strategic Compass. Although not all EU member states see an immediate necessitate for a stagger towards the Indo-Pacific, China is a growing geopolitical maritime rival that can not be overlooked. China now has the worldly concern ’ sulfur largest dark blue to accompany its global net of infrastructure projects, raw material interests and marine investments ( 11 ). Although we should not overestimate the importance of the size of China ’ sulfur united states navy, or the fact that it has already conducted live exercises in the Mediterranean and is expanding its naval root at Djibouti, we should not underestimate China ’ s overall nautical baron. Beijing may not be a traditional sea world power ( 12 ) but its quickly growing commercial embark diligence, its shipbuilding market and its ownership of ports infrastructure make it a nautical world power. While China may not so far search naval conflict beyond its contiguous maritime vicinity, it does use its navy to protect chinese fishing fleets that operate in places like Ghana or the Galapagos ( 13 ). Beijing besides uses its maritime bearing to undergird the activities of large state-owned enterprises ( SOEs ), which produce the largest plowshare of chinese goods and services ( 14 ) and export China ’ south economic model — one at odds with Europe ’ second .

Europe ’ south navies have a crucial role to play in maritime surveillance and intelligence .

however China ’ s growing maritime world power is not plainly a refer from a naval position. In fact, one of the challenges facing the Strategic Compass will be how to efficaciously respond to the increase of nautical hybrid threats. The UN Convention for the Law of the Sea ( UNCLOS ), the UN Charter and accustomed international law model ambiguously alongside each other and none of these legal instruments cover the practice of storm at sea and non-military maritime conflict at the like time. This is why it is unmanageable to craft responses to the construction of artificial islands, illegal backbone dredge and sea mining, the collision of civil and military vessels, civil harassment of naval vessels, submarine threats or the use of fishing vessels or coastguards as proxy ‘ nautical militia ’ ( 15 ). Legal ambiguity and the congestion built-in in the maritime knowledge domain give rise to legal and regulative loopholes that can become security vulnerabilities ( 16 ). China exploits these vulnerabilities through a tactic of combining military and police forms of nautical compulsion ( 17 ) .

There can not be any ambitious EU nautical security presence without investments from member states and a commitment to use naval capabilities .

These hybrid tactics are not used by China alone. Turkey is employing alike methods in the Mediterranean through its use of survey vessels to illegally drill in Cyprus ’ s territorial sea and EEZ. Maritime security closer to the EU is, therefore, another pressing issue for the Strategic Compass. Consider that the EU has a coastline of 68 000 kilometer and over 2 000 dwell islands ( 18 ) and the Baltic, Black, Mediterranean and North Seas are besides implicated in security system or geopolitical risks. hera, Russia remains a regional concern and the modernization of its bomber fleet and long-range preciseness hit capabilities means that Moscow can threaten Europe via the Atlantic, the High North and Mediterranean Sea. Russia ’ s dark blue already makes practice of long-range Kalibr and short-range Iskander missiles, and they have used them from theatres such as the Mediterranean. additionally, Russia has besides sought to deploy hybrid tactics at ocean, as can be seen from the construction of the Kerch bridge or its intimidation of workers laying submarine cables beneath the Baltic Sea .

Maritime power: The berth of the Strategic Compass

Given the multitude of nautical threats, risks and challenges facing the EU it is necessary to reflect upon the ways in which the Strategic Compass could enhance the Union ’ s approach to maritime security system. We have seen that maritime security concerns are diverse and they emerge across different policy domains and geographic areas. concrete policy ideas will have to immediately respond to the threats outlined above, but it is worth acknowledging that responses can not be framed entirely in naval or hard might terms. A challenge will be how to balance the EU extremity states ’ vary approaches to maritime security. It will besides be a test to ensure complementarity between EU maritime security and the Union ’ s crisis management and capacity build efforts on land, adenine good as the EU ’ s broader efforts on ocean government. With these caveats in thinker, we now reflect on how nautical security could be treated by each of the four, interlocking, baskets of the Strategic Compass .

Crisis management

This beginning basket of the Strategic Compass should provide greater clearness for the types of EU naval deployments expected over the adjacent 5-10 years. Consider that most european combat forces are still adapted to deployments in arid locations such as Afghanistan or the Sahel, and, with the exception of certain navy or marine forces, there is little late cognition of amphibious deployments in tropical zones such as those found in West Africa, East Africa or the Indo-Pacific. This is concerning if the EU is expected to respond to crises in these zones in the future. Keep in take care that approximately 40 % of the worldly concern ’ s population or closely 2.4 billion people reside within 100 km of coasts ( 19 ). Consider besides the amphibious forces and capabilities that would have been required had the Union decided to repel the Islamist attack on the Port of Palma, Mozambique, in March 2021. These types of interventions could become more likely in future given the miss of patrol and littoral capacities of coastal states ( 20 ) and the EU ’ s need to ensure safe SLOC for trade. Given the disruptive affect of climate exchange, it is besides likely that the EU might have to deliver humanist aid in or close to coastal zones affected by extreme weather events and/or temperatures ( 21 ) .

The Compass could reformulate how the EU ties up its naval and land-based operations and missions. Despite its experiences in the Horn of Africa, the EU is not train to engage in amphibious operations in geopolitically contested nautical areas and to follow this up with country forces, if thus required. A continuous and credible EU naval presence in littoral zones in the Gulf of Guinea, the Mediterranean, East Africa and the Indo-Pacific would have a deterrent effect and amphibious forces and associated sea-air assets could conduct nautical especial operations, rescue and elimination missions and support human-centered efforts in case of climate-induced disasters. amphibious forces could besides provide the EU with an operational capacity shortstop of the deployment of larger units, if this is operationally required ( 22 ). It should not be overlooked that a more continuous and credible at-sea presence is probably to be welcomed by close partners dealing with China ’ s growing naval power and it would contribute to the Union ’ s overall diplomatic bearing in regions like the Indo-Pacific .

These amphibious forces could in time become a potential permanent Structured Cooperation ( PESCO ) project linking to existing and future projects such as ‘ co-basing ’, amphibious rape ships, precision-guided munitions, high-speed craft, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance ( ISR ) and air ability capacities. In case of a motivation for follow-on forces after amphibious deployments, the EU could explore what role the EU Battlegroups, the PESCO project ‘ EUFOR Crisis Response Operation Core ’ ( CROC ) or other future EU entrance power initiatives could play. amphibious operations are challenging, but they are an indispensable part of maritime strategy and look probable to increase in importance. The challenge for the EU in creating such amphibious forces would be how to invest in enablers such as air out assets and operational sustainability. For example, such forces are easier to supply in the Mediterranean Sea but without host bases in locations such as the Indo-Pacific logistics will be challenging. Basing and logistics could possibly be a stress of discussion under the recently announced EU-US dialogue on defense .

The Compass could besides underline the importance of EU nautical exercises, particularly given their growing relevance to the EU ’ s maritime partnerships — the EU and Japan have conducted pass exercises ( PASSEX ) in the Horn of Africa. Yet, nautical exercises offer the Union a luck to develop its civil-military coordination efforts besides. An matter to model that could be emulated under the Compass is the COASTEX exercises that are jointly organised by the european Fisheries Control Agency ( EFCA ), the european Maritime Safety Agency ( EMSA ), the european Border and Coast Guard Agency ( Frontex ) and member state authorities. For political reasons it may be unreasonable to expect Common Security and Defence Policy ( CSDP ) actors to participate in COASTEX, but EU-led live naval exercises could include EFCA, EMSA, Frontex and member department of state and partner nautical authorities in an incorporate approach to tackling maritime security challenges, loanblend threats and climate-induced disasters.

Resilience

The basket on resilience could outline a more coherent EU approach to maritime security. The EU is issuing a host of maritime-related documents on connectivity, the blasphemous economy, the Indo-Pacific, ocean administration, the Arctic, nautical security and security system and defense, but this comes with the risk of overlap and policy gaps. One way of managing overlap is to combine and replace existing strategies. Given the loanblend nature of nautical threats, an obvious place to start would be to merge the EU Maritime Security Strategy ( EUMSS ) ( 23 ) and the Joint Communication on International Ocean Governance ( IOG ) ( 24 ) through a consolidated strategic document. The process behind such an feat would besides encourage the european Commission and the European External Action Service ( EEAS ) to work much more closely together on maritime security. It is worth recalling that the adjacent phase in the implementation of the EUMSS Action Plan is anticipate for early 2022 – frankincense, at the lapp time as the delivery of the Strategic Compass. In time, the EU could consider combining the EUMSS and the joint communication on IOG with the newly published communication on a sustainable blue economy .

however, nautical resilience does not depend on scheme documents alone but policy action designed to protect maritime infrastructure auspices – a key feature of speech of countering maritime loanblend threats. distinctly, marine infrastructure will be chiefly protected by commercial actors that operate ports, energy installations and submarine cables. The europium can support these efforts through its financing instruments under the Multiannual Financial Framework ( MFF ) and with regulative means such as the extroverted revision of the 2008 Critical Infrastructure Protection ( CIP ) Directive, the Network and Information Systems ( NIS ) Directive, plus the existing foreign target investing screening mechanism. The EU could play a function in investing in new technologies to protect submarine cables and landing stations. Although chiefly a regulative consequence, one can not so easily discount a potential character for Europe ’ second navies — it is worth asking whether civilian authorities would be able to respond to a hostile attack on submarine cables on their own or to deal with undischarged artillery in places like the Baltic and North Seas. It is worth noting that military mobility tape drive networks would besides benefit from enhanced marine critical infrastructure auspices in the EU .

Europe ’ s navies have a crucial role to play in nautical surveillance and news, even if such a function is today hampered by the atomization of data collection, imaging and sensing efforts. In this esteem, the Compass could push the acerate leaf towards a serious rationalization of the Union ’ s existing nautical surveillance capacities. For model, the ‘ MARSUR ’ project spearheaded by the european Defence Agency ( EDA ), which enables dialogue across european naval information systems, has only tentatively begun communicating with the EU ’ s Common Information Sharing Environment ( CISE ), which links together approximately 300 nautical surveillance authorities to monitor illegal fishing, pollution and edge control ( 25 ). This joint attempt provides for an automatic exchange software that besides relies on geospatial intelligence gathered by the EU Satellite Centre ( SatCen ) and maritime data provided by EMSA and Frontex through services such as Copernicus .

however, some of the most authoritative maritime surveillance capacities available to the Union are not held in the hands of defense actors at all. EMSA uses remotely piloted aircraft systems to detect maritime pollution and emissions, ensure boundary line monitor and counter illegal fish. furthermore, EMSA oversees the SafeSeaNet monitor service for vessel traffic in EU waters. Frontex is besides responsible for a rate of nautical surveillance activities and along with member states it manages the european Border Surveillance System ( EUROSUR ) model to develop situational awareness for cross-border crime and irregular migration. Since 2018, Frontex has developed a Maritime Intelligence Community & Risk Analysis Network ( MIC-RAN ) to collect data and circulate risk analysis products on nautical threats, risks and challenges ( 26 ). MIC-RAN relies on a range of civil authorities, but military actors are part of the network excessively. Frontex, EFCA and EMSA have besides recently increased their maritime situational awareness activities for coast guard duty and border purposes ( 27 ) .

so far for all of these capacities there is no individual nautical surveillance hub at the EU flat that can respond to the needs of civil and military actors operating in the maritime domain. If the EU is to be able to collect, wangle and act on maritime data in a coherent way there is a need to better connection CISE, EUROSUR, MIC-RAN and SafeSeaNet with defence-specific capacities such as MARSUR, SatCen, the Hybrid Fusion Cell and the EU ’ s Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity ( SIAC ). accordingly, the Compass could either suggest ways of improving nautical surveillance coordination within the current structures or call for the creation of a centralising hub such as a ‘ Maritime Task Force ’ or a ‘ Maritime Fusion Cell ’. Either room, there is a growing necessitate for a single desegregate maritime situational awareness word picture that can simultaneously cover maritime security, nautical hybrid threats, climate-related crises, critical infrastructure auspices, plagiarism and more. Such a arrangement is not plainly required for CSDP-related activities, but besides the Union ’ s civil protection efforts, border management and its reciprocal aid and solidarity obligations .

Capabilities

If it is discipline to assume that the EU faces geopolitical competition, maritime hybrid threats and the effects of climate-induced nautical risks over the future 5-10 years, then this will call for clear capability priorities. It should be stated plainly that there can not be any ambitious EU maritime security presence without investments from penis states and a commitment to use naval capabilities. Yet, modest steps are being made. Through PESCO and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence ( CARD ), it has already been revealed that a european Patrol Corvette will be developed by 2030 for maritime security efforts in waters close to european territory ( 28 ). PESCO is besides home to six specific maritime projects that target mine countermeasures, maritime surveillance, submerged intervention, unmanned anti-submarine systems and patrol vessels — many more PESCO projects are relevant to the maritime knowledge domain ( e.g. distance, logistics and cyber ). The CARD process has revealed that 12 out of 55 capability development opportunities identified in 2020 relate to the maritime world. What is more, in meter the EU ’ s investments in space-based capabilities will besides enhance the Union ’ s nautical security capabilities .

The european Defence Fund ( EDF ) can be expected to invest in the maritime world excessively, and its preparatory stages have already made investments in electromagnetic railguns, preciseness affect and nautical surveillance. We besides know that the first base call under the EDF will dedicate €103.5 million to naval combat capabilities in 2021, but there is a motivation to invest in strategic nautical platforms and enablers in the future. The recently published Action Plan on Synergies between the civil, defense and space industries could besides unlock maritime sector invention by blending existing EU fiscal tools. At confront, european navies lack the high-end naval capabilities that would be required to undertake coincident SLOC operations. There is a miss of aircraft carriers, submarines, surface combat ships, mine countermeasures vessels, amphibious ship, corroborate vessels, offshore patrol vessels and personnel ( 29 ). Developing some of these capabilities under PESCO or the EDF would be a gauge of how ambitious EU member states are about maritime security .

however, naval platforms alone will not be enough to ensure the EU ’ s maritime security. Just as important will be investments in promote nautical sensors, space-based assets, propulsion, remotely piloted nautical and aeriform vehicles, marine robotics, directed energy and laser capacities, digital connectivity, preciseness strike and missile defense and an ability to use AI to manage huge amounts of maritime data produced by ports, marine operators and seafarers. There is besides a want to counter the increased use of loitering munitions and drones at sea. Without such capacities, Europe will continue to lag behind the United States and China in maintaining its naval presence. The Compass could spell out how european union penis states will achieve greater stealth, range and deadliness at ocean with specific timeframes for pitch and call for a healthy desegregate of naval platforms and enabling systems and technologies ( 30 ) .

Partnerships

Over the following 5-10 years closer EU-NATO and EU-US cooperation will be necessity, specially with attentiveness to maritime security in areas such as the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, the High North and the Mediterranean, and in light of the fact that a boastfully separate of Europe ’ s ballistic projectile defense ( BMD ) is provided at ocean through the Alliance. The NATO 2030 Report has already called for an update of the Alliance Maritime Strategy and closer EU-NATO consultations about nautical security in the southern proportion. This will not be easy given current tensions with Turkey over its truculent activities in the eastern Mediterranean. EU-NATO maritime cooperation will besides be moulded by the competing demands of enhancing NATO Standing Naval Forces in order to deter Russia, and increasing US-led initiatives to ensure the Alliance responds to China in the Indo-Pacific. In such a context, lone a significant and sustain addition in naval platforms and enablers over the future few decades will allow european navies to meet their responsibilities in the EU and NATO .

Another key return related to partnerships will be how the EU can enhance its naval cooperation in the future with the United States, the United Kingdom, India, Australia, Japan, South Korea and others. For the time being, we should expect bilateral or minilateral modes of naval cooperation such as close France-US-UK exercises and Freedom of Navigation operations ( FONOPs ) to be the average. In clock, however, the EU could develop a elastic and attractive maritime cooperation framework — not least to allow Denmark to play a greater function without calling into interrogate its military opt-out from the CSDP. The CMP, a non-CSDP joyride designed to ensure communication between european navies operating in particular maritime zones, could be the flexible model the Union and its partners need. The CMP is presently being refined in the Gulf of Guinea, but the plan is to expand it to the indian Ocean. In addition to enhancing its geographic strive, the CMP could in time become a accommodative anchor for the EU and partners to exchange nautical intelligence, exercise together and create ad hoc naval groups. Regional CMPs could evening be physically embedded in maritime hub or naval bases to bring together EU coastguard, customs or naval officers with officials from regional and external organisations and partner navies. More ambitious regional CMPs could besides help deliver maritime capacity building with the aid of the european Peace Facility ( EPF ) .

The Strategic Compass could besides underline the importance of existing nautical capacitance building mechanisms such as the Critical Maritime Routes ( CMR ) program, which supports coastguard and nautical law enforcement capability build up in 40 countries in the Gulf of Guinea and the indian Ocean. The Compass can draw on the design expansion of CMR to South East Asia, and, potentially, to the Southern Pacific ( 31 ). A similar expansion of the EU-financed Maritime Security Programme ( MASE ) to these regions could be explored in decree to combat piracy and parcel information in the broader Indo-Pacific with regional organisations, UN bodies and Interpol. The EU can besides work closely with newly established bodies such as The Atlantic Centre to engage raw maritime partners in the Atlantic Ocean, and bolster its presence in the Shared Awareness and De-Confliction ( SHADE ) forums while besides exploring ways of expanding the model to Asia .

Oceans apart? EU maritime ambitions and the realities

Unlike the United States and China, which net income from a proportional abundance of nationally sourced bleak materials and industrial capability, Europe survives on its maritime interdependences. As this Brief has argued, maritime security threats, risks and challenges are mounting in core geopolitical areas that have a direct bearing on the EU ’ s security and economic prosperity. There is no way around the fact that no good EU level of ambition in nautical security can be achieved without investments and capabilities. naval power is a critical component of the EU ’ s overall maritime ambitions. The reality nowadays is that, with the exception of lone a few european states, maritime power in Europe has been neglected and this has hit overall naval unit of measurement numbers. This affects both the EU and NATO. If Europe is good about maintaining dislodge access to the global commons and maintaining its economic baron, this situation must change quickly .

No serious EU level of ambition in nautical security can be achieved without investments and capabilities.

Read more: What is the Maritime Industry?

however, greater european nautical exponent can not be calculated entirely in terms of the number of naval vessels member states own. naval office and maritime power are related, but clear-cut. There can be no coherent nautical scheme for the EU without clarity on why the maritime domain is intrinsic to european security, freedom and prosperity or how and where Europe should act to safeguard its interests and values. accordingly, the Strategic Compass can distinctly articulate an operational scheme that links together sea, air, state, cyber and space domains. The compass can besides underline that the EU is uniquely placed to generate maritime power particularly if it successfully fuses its trade and investment, partnership, connectivity and security and defense policies. This fusion will require joint management of nautical security by the Commission and the EEAS, but this is what was surely implied by the European Council when it called for the Strategic Compass to make ‘ practice of the stallion EU toolbox ’ ( 32 ) .

References

* The author would like to thank Fabio Agostini, Matteo Bressan, Paulo Alexandre de Campos, Armando Dias Correia, Hervé Delphin, Bruno Dupré, Florence Gaub, Michalis Ketselidis, Jean-Marie Lhuissier, Athanasios Moustakas, Alessio Patalano, Jukka Savolainen, Lars Schümann, Stanislav Secrieru and Ricardo Miguel Alves Teixeira for their feedback on and/or support for this Brief. The writer would besides like to thank the portuguese Presidency of the Council of the EU, the french Permanent Representation to the EU and the Strategic Planning Division at the European External Action Service for their cooperation with organising a series of events on maritime security during 2021. These events further refined the contents of this Brief .

(1) Vavasseur, X., ‘ French Carrier Strike Group Begins “ Clemenceau 21 ” Deployment ’, Naval News, 23 February 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.navalnews.com/ naval-news/2021/02/french-carrier-strike-group-begins-clemenceau-21- deployment/ ).

(2) German Federal Ministry of Defence, ‘ U.S. Secretary of Defense on his First Official Visit with German Counterpart ’, 13 April 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.bmvg.de/ en/news/us-secretary-of-defense-visits-german-defence-minister-5054754 ).

(3) French Ministry of the Armed Forces, ‘ Mission MARIANNE – united nations exemple de coopération entre forces de surface et forces sous-marines ’, 18 May 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.defense.gouv.fr/marine/actu-marine/mission-marianne-un- exemple-de-cooperation-entre-forces-de-surface-et-forces-sous-marines ).

(4) european Commission, ‘ Maritime year : EU priorities and actions ’, 5 June 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/maritime/maritime-transport_ en ).

(5) See for example, Allianz, ‘ Rising Geopolitical Tensions Threaten Global Shipping ’, 15 July 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.agcs.allianz.com/news-and-insights/ expert-risk-articles/shipping-2020-geopolitical-tensions.html ).

(6) UNCTAD, ‘ Review of Maritime Transport 2020 ’, 12 November 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : // unctad.org/webflyer/review-maritime-transport-2020 ).

(7) Kirezci, E. et aluminum, ‘ Projections of global-scale extreme point sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flood over the twenty-first Century ’, Scientific Reports, Vol. 10, No 11629, July 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-67736-6 ).

(8) european Defence Agency, ‘ First High-Level Joint Defence and Energy Meeting – event Report ’, 10 May 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //eda.europa.eu/docs/default- source/consultation-forum/event-report/event-report-v-1-6.pdf )

(9) See : www.submarinecablemap.com.

(10) Fiott, D. and Theodosopoulos, T., ‘ Sovereignty over Supply ? The EU ’ s ability to Manage Critical Dependences while Engaging with the World ’, Brief, No 21, EUISS, December 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //mindovermetal.org/en/sites/default/files/ EUISSFiles/Brief % 2021 % 20Supply.pdf ).

(11) Duchâtel, M. and Duplaix, A.S., ‘ Blue China : Navigating the Maritime Silk Road to Europe ’, Policy Brief, European Council on Foreign Relations ( ECFR ), 23 April 2018 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //ecfr.eu/publication/blue_china_navigating_the_ maritime_silk_road_to_europe/ ).

(12) One technical argues that China ’ s continental landmass and political system largely inhibit its ability to become a ocean power in the traditional sense, even if its political dominance of the nautical knowledge domain would be black for free democracies. Lambert, A.D., Sea Power States : nautical culture, Continental Empires and the Conflict that Made the Modern World, Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 2018, p. 321.

(13) Yap, C-W, ‘ China ’ s Fishing Fleet, the World ’ south Largest, Drives Beijing ’ randomness Global Ambitions ’, The Wall Street Journal, 21 April 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.wsj.com/ articles/chinas-fishing-fleet-the-worlds-largest-drives-beijings-global- ambitions-11619015507 ).

(14) Garcia-Herrero, A. and Ng, G., ‘ China ’ s state-owned enterprises and competitive neutrality ’, Bruegel Policy Contribution, No 5, February 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : // www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/PC-05-2021.pdf ).

(15) Moore, C. Freedom of Navigation and the Law of the Sea : Warships, States and the Use of Force, Routledge, London/New York, 2021, p. 5.

(16) Lohela, T. and Schatz, V. ( eds. ), ‘ Handbook on Maritime Hybrid Threats – 10 Scenarios and Legal Scans ’, Hybrid CoE Working Paper, No. 5, 22 November 2019 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.hybridcoe.fi/publications/hybrid-coe-working-paper-5- handbook-on-maritime-hybrid-threats-10-scenarios-and-legal-scans/ ).

(17) Patalano, A., ‘ When Strategy is “ Hybrid ” and not “ Grey ” : Reviewing taiwanese Military and Constabulary Coercion at Sea ’, The Pacific Review, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2018, pp. 811-839.

(18) Haase, D. and Maier, A., ‘ Islands of the European Union : state of matter of Play and Future Challenges ’, Study for the REGI Committee, March 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : // www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/652239/IPOL_ STU ( 2021 ) 652239_EN.pdf ).

(19) United Nations, ‘ Factsheet : People and Oceans ’, June 2017 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www. un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Ocean-fact- sheet-package.pdf ).

(20) For an account of nautical security in the Mozambique Channel see : Decis, H., ‘ The Mozambique Channel – Troubled Waters ? ’, IISS Military Balance Blog, 7 May 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/05/ mozambique-channel-maritime-security ).

(21) Council of the European Union, ‘ Climate Change and Defence Roadmap ’, 12741/20, 9 November 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ ST-12741-2020-INIT/en/pdf ).

(22) Roberts, P., ‘ The future of amphibious Forces ’, The RUSI Journal, Vol. 160, No. 2, 2015, pp. 40-48.

(23) european Commission, ‘ Maritime Security Strategy ’ ( hypertext transfer protocol : //ec.europa.eu/ oceans-and-fisheries/ocean/blue-economy/other-sectors/maritime-security- strategy_en ).

(24) ‘ Joint Communication on International Ocean Governance : An Agenda for the future of our Oceans ’, JOIN ( 2016 ) 49 final, 10 November 2016 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www. eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/resources/docs/join-2016-49_en.pdf ).

(25) Huotari, A. and Tikanmäki, I., ‘ An Online educate for the EU Common Information Sharing Environment ’, 2015 Second International Conference on Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Social Media ( CSCESM ), 2015, p. 156.

(26) Council of the European Union, ‘ Joint Staff Working Document – Report on the Implementation of the Revised EU Maritime Security Strategy Action Plan ’, 12310/20, 26 October 2020, p. 26 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/ document/ST-12310-2020-INIT/en/pdf ).

(27) Frontex, ‘ Frontex, EMSA and EFCA to strengthen cooperation on coast guard functions ’, 19 March 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/ news/news-release/frontex-emsa-and-efca-to-strengthen-cooperation-on- coast-guard-functions-L6oFcf ).

(28) european Defence Agency, ‘ 2020 CARD Report – administrator Summary ’, 2020 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/reports/card-2020-executive- summary-report.pdf ).

(29) These capability assumptions are based on the IISS ‘ Operation Nemo ’ scenario of six coincident SLOC operations during a brusque of war scenario. See : Barrie, D. et aluminum, ‘ Defending Europe : Scenario-based capability Requirements for NATO ’ mho european Members ’, International Institute for Strategic Studies, April 2019, p. 14.

(30) Bowers, I. and Kirchberger, S., ‘ not so disruptive After All : The 4IR, Navies and the Search for Sea Control ’, Journal of Strategic Studies, ( forthcoming ) ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402390.2020.1848819 ).

(31) Council of the European Union, ‘ EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo- Pacific – Council Conclusions ’, 7914/21, 16 April 2021, p. 8 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //data. consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7914-2021-INIT/en/pdf ).

(32) ‘ Statement of the Members of the European Council ’, SN 2/21, 26 February 2021 ( hypertext transfer protocol : //www.consilium.europa.eu/media/48625/2526-02-21-euco- statement-en.pdf ) .