The intertwining nature of China’s economic opening and strategic development

Over the last respective decades, the world has observed the meteoric advance of taiwanese economic power, following the ‘ opening up ’ of its economy in the late 1970s. While the economic authorization and battle of China has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and benefited consumers of Chinese-produced goods global, it has besides led to historic improvements in chinese military, and specially naval, ability. This process has not been plainly a matter of China having extra funds available for military purchases, and then spending them consequently. rather, it has been a self-reinforcing cycle where the growing array of Chinese overseas economic interests and investments has driven increased chinese perceptions of insecurity — on top of historical grievances and long-simmering tensions related to sovereignty and territorial issues in places such as Taiwan, the Senkaku Islands, and the South China Sea. This palpate of insecurity is most clearly illustrated in what was described by early Chinese president of the united states Hu Jintao in 2003 as China ’ mho “ Malacca dilemma ”, a recognition that China ’ s energy supplies could be interdicted by hostile foreign nations in strategic locations such as the Strait of Malacca. Prior to China ’ s industrial development, no such dilemma existed. But as China ’ mho economy continues to grow and become ever more dependant on access to oversea resources and markets, this feel of insecurity, vitamin a well as the resulting appetite for the military means to reduce it, continues to grow .

On 23 April this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping showed off the PLA Navy’s production capacity by commissioning at a single ceremony the Hainan amphibious assault ship, the Changzheng-18 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, and the Dalian destroyer. Image: Li Gang/Xinhua via Getty Images. Before this march of economic growth and military modernization began, the PLA had basically no ability to directly harm Australia ’ s full of life national interests or territorial integrity. While the PLA possessed one of the earth ’ randomness largest crunch forces, it had little ability to project power outside the nation ’ s borders. At ocean, early PLA Navy ( PLAN ) doctrine was focused on coastal defensive structure, [ 1 ] with no very ability to interdict Australia ’ s sea lines of communication ( SLOCs ). The PLA Air Force ( PLAAF ) had no forward bases, no air-refuelling capability, and very limited draw missile capability. China ’ s land-based missile forces — known today as the PLA Rocket Force ( PLARF ) — consisted of small numbers of long-range nuclear-armed missiles, adenine well as conventional ballistic missiles excessively inaccurate to hit anything but cities .

On 23 April this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping showed off the PLA Navy’s production capacity by commissioning at a single ceremony the Hainan amphibious assault ship, the Changzheng-18 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, and the Dalian destroyer. Image: Li Gang/Xinhua via Getty Images. Before this march of economic growth and military modernization began, the PLA had basically no ability to directly harm Australia ’ s full of life national interests or territorial integrity. While the PLA possessed one of the earth ’ randomness largest crunch forces, it had little ability to project power outside the nation ’ s borders. At ocean, early PLA Navy ( PLAN ) doctrine was focused on coastal defensive structure, [ 1 ] with no very ability to interdict Australia ’ s sea lines of communication ( SLOCs ). The PLA Air Force ( PLAAF ) had no forward bases, no air-refuelling capability, and very limited draw missile capability. China ’ s land-based missile forces — known today as the PLA Rocket Force ( PLARF ) — consisted of small numbers of long-range nuclear-armed missiles, adenine well as conventional ballistic missiles excessively inaccurate to hit anything but cities .

As the international telescope of China ’ mho economic interests has expanded, China ’ s strategic horizons have broadened correspondingly. Following China ’ mho economic opening, the mid-1980s saw the first transformation of the PRC ’ s naval strategy under Admiral Liu Huaqing, from its traditional coastal defense mission to one of “ offshore defense ” of China ’ south near sea — that is, out to the First Island Chain, which runs from Malaysia up through Indonesia, the Philippines, and Japan. [ 2 ] China ’ second leaders established a timeline with three broader goals for the plan : by 2000, developing forces sufficient to exert control over the ocean regions within the First Island Chain ; by 2020, extending control out to the Second Island Chain, running from Papua New Guinea up through the Mariana Islands to northern Japan ; and by 2050, to develop a sincerely global united states navy. [ 3 ]

China appears to have the motivation, nautical industrial might, and resolve to give its words an wholly unlike mean : a declared strategy that, if actualised, would take the shape of military — and specially nautical — capability of a scale that many western observers are however to in full comprehend.

In 2004, President Hu provided a further update to the PLA ’ s steering with a contract of “ New Historic Missions ” that broadened the PLA ’ second goals to encompass “ far seas defense ”, covering seas past the First Island Chain and come out of the closet into the open Pacific Ocean and beyond. The PRC ’ s 2015 Defence White Paper explicitly included defense of overseas interests and strategic SLOCs in its goals, to be accomplished by the add mission of “ outdoors seas protection ”, signalling a need to be able to project maritime might wherever China ’ sulfur interests lie. [ 4 ] The 2019 Defence White Paper continued this theme, declaring a necessitate to develop “ far sea forces ”, overseas establish facilities ( a previously-disavowed practice for China ), and enhanced “ capabilities in accomplishing diversify military tasks ”. [ 5 ] As outgoing PLAN chief, Admiral Wu Shengli stated upon his passing from position in 2017, “ wherever the setting of the nation ’ second interests extends, that is where the perimeter of our battle growth will reach ”. [ 6 ]

China ’ s desire to protect its oversea interests and defend its SLOCs might be regarded as analgesic ; after all, such an objective on the region of other nations would raise fiddling alarm. But this is largely because, in about all cases, those nations lack the ability to defend their SLOCs on a ball-shaped basis. China appears to have the motivation, maritime industrial might, and resolve to give its words an wholly unlike meaning : a express scheme that, if actualised, would take the form of military — and specially maritime — capability of a scale that many western observers are however to fully comprehend .

In terms of the facilities necessary to underwrite expanding chinese power projection and ocean control condition across the Indo-Pacific, we can already see that China has been engaged in a massive crusade to build air and nautical facilities spanning the area, largely under the banner of the Belt and Road Initiative ( BRI ). apparently an feat focused on economic growth, many of its resulting projects fall in highly strategically utilitarian places, and are frequently of an un-economic nature ( see the huge port adeptness and nearby airfield built at Hambantota, Sri Lanka ; [ 7 ] or the under-utilised [ 8 ] but still expanding port facility at Gwadar, Pakistan [ 9 ] ). One should consider besides China ’ mho now well-publicised and explicit policy of “ military–civil fusion ”, wherein state-owned enterprises ( SOEs ) are required by taiwanese law to “ leave necessity support and aid to national security bodies, public security bodies, and relevant military bodies ”. [ 10 ] This concept brings into a new light structure in locations such as Cambodia ’ s Ream Beach, [ 11 ] vitamin a well as Papua New Guinea ’ s Manus Island, [ 12 ] in the strategic approaches to the Antipodes .

As for China ’ s claims of the passive and civilian nature of facilities it is building overseas, one should keep in mind President Xi Jinping ’ s personal pledge, delivered directly to President Barack Obama in the White House Rose Garden, that China would not militarise the South China Sea. That same South China Sea is now dominated by huge artificial islands [ 13 ] that bristle with taiwanese missiles, and which appoint fair the beginning of what it likely to be a series of potent points positioned to help establish chinese control over its critical SLOCs .

Manifestations of the development of Chinese military power

Some observers assert that China ’ s growing military office is a “ banal reality ” intended to “ defend against perceived threats in its offshore waters, as any nation would do ”. [ 14 ] But were China building a military truly focused on largely defensive objectives, one would expect to see an stress on smaller bodyguard ships, coastal defense missiles, fighter aircraft, and the like. alternatively, China has engaged in the largest and most rapid expansion of maritime and aerospace office in generations. Based on its oscilloscope, scale, and specific capabilities, this buildup appears designed first to threaten the United States with expulsion from the western Pacific, and thereafter to achieve domination in the Indo-Pacific .

Some of the most obvious manifestations that China ’ s military development is not defensive in nature can be seen in three specific areas : the deployment by the PLARF of huge numbers of long-range ceremonious ballistic missiles ; a major expansion of the capabilities of China ’ s long-range bomber force ; and the explosive emergence of China ’ s blue-water navy .

China’s ballistic missile force

probably the most long-familiar component of this buildup is the huge armory of highly accurate conventionally-armed ballistic missiles fielded by the PLARF. already by far the world ’ sulfur largest, this force continues to grow at a rate that only makes feel for the determination of hard threatening US and allied capabilities in the westerly Pacific. This is most apparent in China ’ s storm of DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missiles ( IRBMs ) — arguably one of the pate jewels of the chinese military .

A 2020 US government report on China’s military and security developments states that Beijing appears to have more than doubled in a single year its inventory of DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile launchers. In 2015, China showed off its weaponry at a military parade to commemorate the end of the Second World War. Image: The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images. The united states government ’ s 2020 Military and Security Developments Involving the People ’ s Republic of China publication reported an apparent more-than-doubling in a single year of China ’ randomness armory of DF-26 IRBM launchers. [ 15 ] This emergence is a good continuation of previous trends : the 2018 report had listed “ 16–30 ” launchers, then 80 in the 2019 report, [ 16 ] and immediately 200 in the 2020 report. In terms of available projectile inventory for those launchers, the report alone lists “ 200+ ” as the calculate phone number. We know from chinese television footage that DF-26 units exercise reloading missiles routinely, and that the missiles have different warhead types that are swappable. [ 17 ] Thus, if each of the 200-odd launchers had entirely one recharge projectile available ( and there may well be more than that ), this would mean an IRBM force of more than 400 missiles, about all configurable to anti-ship or land-attack missions, in accession to the PLARF ’ s hundreds of increasingly capable ground-launched cruise missiles. [ 18 ]

A 2020 US government report on China’s military and security developments states that Beijing appears to have more than doubled in a single year its inventory of DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile launchers. In 2015, China showed off its weaponry at a military parade to commemorate the end of the Second World War. Image: The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images. The united states government ’ s 2020 Military and Security Developments Involving the People ’ s Republic of China publication reported an apparent more-than-doubling in a single year of China ’ randomness armory of DF-26 IRBM launchers. [ 15 ] This emergence is a good continuation of previous trends : the 2018 report had listed “ 16–30 ” launchers, then 80 in the 2019 report, [ 16 ] and immediately 200 in the 2020 report. In terms of available projectile inventory for those launchers, the report alone lists “ 200+ ” as the calculate phone number. We know from chinese television footage that DF-26 units exercise reloading missiles routinely, and that the missiles have different warhead types that are swappable. [ 17 ] Thus, if each of the 200-odd launchers had entirely one recharge projectile available ( and there may well be more than that ), this would mean an IRBM force of more than 400 missiles, about all configurable to anti-ship or land-attack missions, in accession to the PLARF ’ s hundreds of increasingly capable ground-launched cruise missiles. [ 18 ]

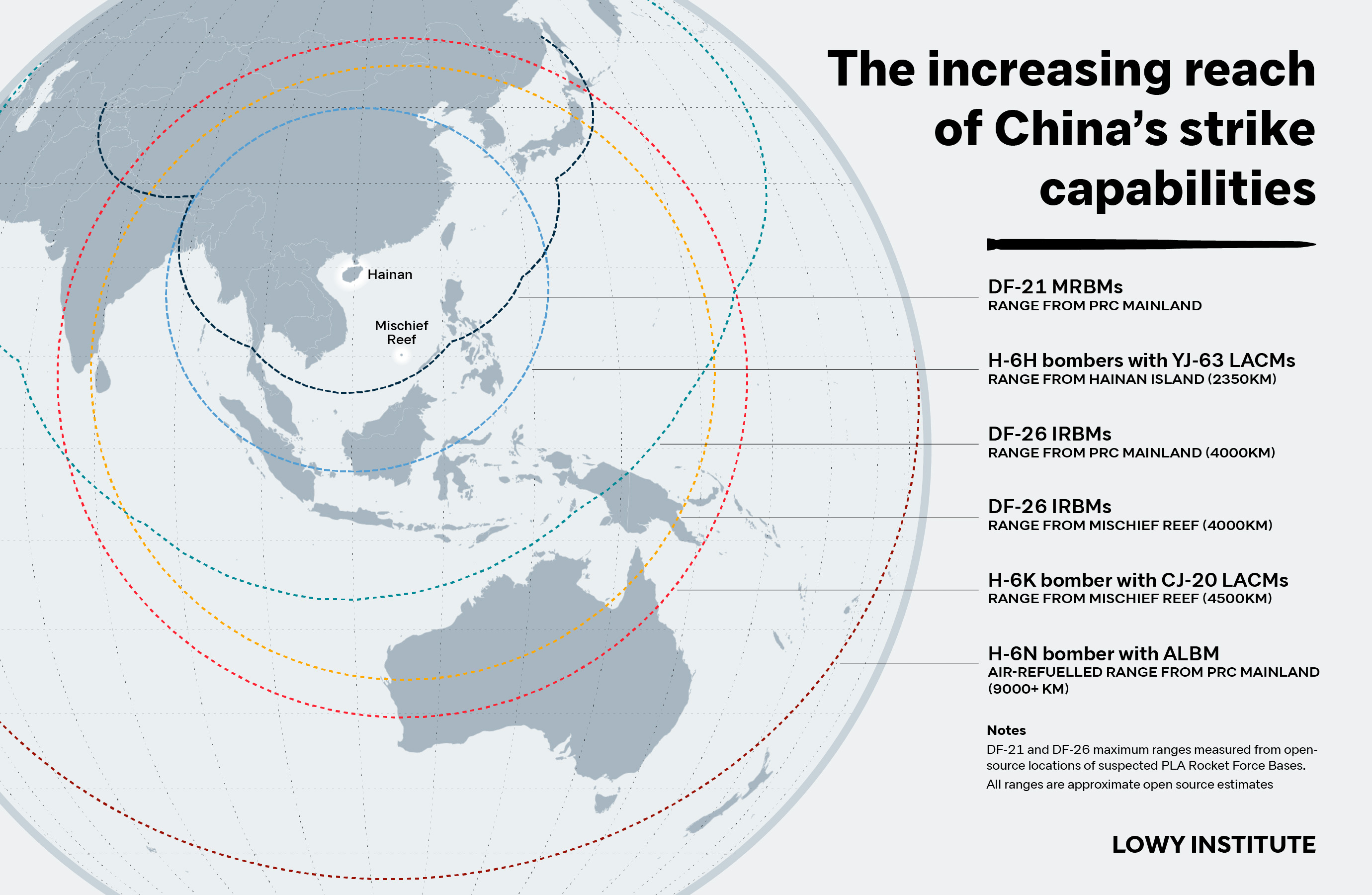

Going from dozens of medium-range missiles to possibly hundreds of much longer-range ones will drive changes to the symmetry of air and maritime ability in the western Pacific on a total of different levels — and with the DF-26 ‘s long range, in the indian Ocean and Persian Gulf, besides ( see Figure 1 ) .

first, the number of available anti-ship ballistic missiles ( ASBMs ) could broaden the PLARF ‘s anti-ship mission from what has been thought of as a ‘ carrier-killer ’ character to a more generic ‘ ship-killer ’ mission, for use not equitable against the United States, but potentially Australia ’ s surface ships equally well. China itself describes the DF-26 as capable against large and medium-sized ships. [ 19 ] Without doubt, in a war at sea the PLA, if it had the inventory to do sol, would be absolutely happy to trade a missile ( or several ), costing possibly in the club of US $ 20 million each, [ 20 ] for a destroyer that would cost billions to replace .

Figure 1: A move by China’s PLA from medium-range to long-range missiles will change the reach and balance of air and maritime power in the western Pacific. Another way in which a DF-26-equipped PLARF could change things would be through the particular extra areas that it could strike ( see Figure 1 ). In the Philippine Sea, areas of relative sanctuary beyond the range of the older and shorter-range DF-21 medium-range ballistic projectile ( MRBM ) lie well within rate of the DF-26. US and allied defense mechanism thinkers previously posited the ability to operate forces sanely safely outside the First Island Chain as a mean to enable episodic operations within that chain, but the risk of such operations is now well higher. [ 21 ]

Figure 1: A move by China’s PLA from medium-range to long-range missiles will change the reach and balance of air and maritime power in the western Pacific. Another way in which a DF-26-equipped PLARF could change things would be through the particular extra areas that it could strike ( see Figure 1 ). In the Philippine Sea, areas of relative sanctuary beyond the range of the older and shorter-range DF-21 medium-range ballistic projectile ( MRBM ) lie well within rate of the DF-26. US and allied defense mechanism thinkers previously posited the ability to operate forces sanely safely outside the First Island Chain as a mean to enable episodic operations within that chain, but the risk of such operations is now well higher. [ 21 ]

While some commentators have expressed incredulity that China ’ s IRBM force could have grown so cursorily, [ 22 ] projectile launchers of this size are discrete physical objects that can be counted from space, so uracil news community assessments are much more than just inference or guess. And while possibly these IRBM launchers are not amply integrated into effective combat units so far, that is merely a matter of time. other observers may have doubted that China ‘s ASBMs actually have the ability to strike moving targets at sea, but the air force officer of US forces in the Indo-Pacific recently confirmed that China ’ s missiles did, in fact, assume moving embark targets during a recent exercise. [ 23 ] Likewise, for the second year in a row, China has launched ASBMs into the South China Sea as separate of an open ocean drill for all to see. [ 24 ] Of notice, China appears to be building a major ballistic projectile base on Hainan Island, bordering the South China Sea. [ 25 ] Given that China could already completely overwhelm any of its regional competitors ’ military forces with the rest of the PLA ’ second forces, it seems probable that this ballistic projectile establish is being built to threaten US aircraft carriers operating in that area in support of its allies and partners .

While China ’ s projectile pull does not presently appear to possess the rate to threaten australian bases immediately from the chinese mainland, if China were to deploy its IRBMs from its South China Sea island bases, that might no farseeing be true.

The threat is by no means restricted to ships. In 2017, a colleague and I at the Center for a New American Security estimated that a preemptive chinese missile hit on US bases in Asia could crater every track and runway-length taxiway at every major US air basal in Japan, and destroy more than 200 aircraft on the ground. [ 26 ] We besides estimated that, in addition to shorter-range missiles, an inventory of approximately 60 DF-21 MRBMs would be necessary to conduct such a come to. [ 27 ] Considering the National Air and Space Intelligence Center ’ s holocene estimate that China now possesses “ approximately 350 ” medium and intermediate-range ballistic projectile launchers, the menace appears to have become dangerous than we estimated at that time. [ 28 ]

To be certain, the PLA ’ s projectile forces are not invincible or unstoppable. While the details are probable to remain classify, the United States is surely working to develop “ leave of establish ” measures to dazzle, decoy, or destroy China ’ s reconnaissance satellites, arsenic well as to jam their missiles ’ seekers if they do manage to launch. One can besides imagine robust efforts to disrupt, whether via kinetic means or otherwise, the links and nodes in China ’ mho dominate and control networks that would be necessary to transmit targeting data from its detector networks to its projectile units. China ’ s early reconnaissance platforms, whether in the publicize, on or under the sea, or on bring, would besides be prime targets for US and allied strike capabilities. The combination of these efforts would mitigate, hopefully to a meaning degree, the threat of China ’ s long-range missiles .

While China ’ s missile power does not presently appear to possess the scope to threaten australian bases directly from the chinese mainland, if China were to deploy its IRBMs from its South China Sea island bases, that might no long be true. additionally, with the ongoing development of future weapon systems — such as hypersonic glide vehicles or the likely development of precise conventional intercontinental-range missiles — there is no clear obstacle to China developing missiles that could strike Australia from its mainland. surely, the clear up vogue over time has been China ’ s growth of precise missiles with ever-greater range, with no clear end point in sight .

China’s long-range bomber force

In addition to its projectile effect, in holocene years China has dramatically increased the capability of its fleet of long-range strike aircraft. China has the populace ’ s lone operating bomber production line, which has been producing brand-new, long-range aircraft apparently purpose-built [ 29 ] to strike US and allied bases, and to overwhelm US and allied carrier strike groups on the high seas. [ 30 ]

Before the last ten, China ’ s bomber violence had fairly specify capabilities. The Xi ’ an Aircraft Company ’ s H-6, a go steady copy of the Soviet-era Tupolev Tu-16, only carried a small numeral of rudimentary missiles and could deliver them to a limited crop. This began to change in 2009 with the initiation of the H-6K, a major redesign and update of the basic airframe. Equipped with completely new engines and avionics, the H-6K enjoys a much longer fight radius ( about 3500 kilometres ) and is adequate to of carrying six missiles compared to two in previous versions. [ 31 ]

The Xian H-6K strategic bomber enjoys a much longer combat radius than its predecessor and is capable of carrying six missiles compared to two in previous versions. Image: Wikimedia commons. Incorporating the improvements provided by the PLAAF ’ s H-6K, the design has since gained its own maritime strike-focused translation of the aircraft — the H-6J. First seen in 2018, the H-6J is capable of carrying six YJ-12 long-range supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles. [ 32 ] More recently, China roentgen evealed the development of a new model, the H-6N, which is able of forward pass refuel and appears to carry a one air-launched ballistic missile with what appears to be a hypersonic glide fomite. [ 33 ]

The Xian H-6K strategic bomber enjoys a much longer combat radius than its predecessor and is capable of carrying six missiles compared to two in previous versions. Image: Wikimedia commons. Incorporating the improvements provided by the PLAAF ’ s H-6K, the design has since gained its own maritime strike-focused translation of the aircraft — the H-6J. First seen in 2018, the H-6J is capable of carrying six YJ-12 long-range supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles. [ 32 ] More recently, China roentgen evealed the development of a new model, the H-6N, which is able of forward pass refuel and appears to carry a one air-launched ballistic missile with what appears to be a hypersonic glide fomite. [ 33 ]

calculate 1 shows such a progress of capability relative to the australian celibate, with China ’ second older H-6H model ineffective to reach australian targets at all ; today ’ mho H-6K able to reach northwest Australia if dispatched from China ’ south bases in the South China Sea ; and finally China ’ s air-refuellable H-6N able to strike anywhere in Australia from bases in mainland China. While we are so far to see military aircraft permanently based at China ’ s artificial island bases, the facilities built on them — retentive runways, big aircraft hangars, and acres of hardened fuel tanks [ 34 ] — appear well-suited to support operations by larger aircraft such as China ’ s bomber flit .

It is crucial to note that China is not merely replacing older bombers with improved ones ; it appears to be growing the size of the force vitamin a well. Prior to the introduction of the H-6K, most estimates were that China ’ s H-6 stock was in the mid-to-low 100s. [ 35 ] In order to determine the approximate size of China ’ s bomber force over the last several years, the generator conducted two surveys of available commercial satellite imagination, using open-source lists of chinese bomber bases. These counts, which did not include any aircraft in flight, in hangars, deployed to junior-grade airfields, or otherwise missing from imagination, produced results of merely over 200 aircraft in 2018, and more than 230 in 2020 .

China as a maritime world power

In holocene decades, China has grown to become the universe ’ south chancellor sea exponent by most measures. China already holds beginning plaza in the size of its fishing, merchant ship, and nautical jurisprudence enforcement fleets. [ 36 ] China ’ s shipbuilding diligence dwarf that of the United States, building 38 million tons of shipping in 2020 compared to just over 70 000 tons from american english yards. [ 37 ] The same is on-key in maritime law enforcement, with China building slide precaution cutters and “ maritime base hit ” vessels weighing over 10 000 tons — larger even than the latest western destroyers. [ 38 ] China ’ s fishing fleet, besides the world ’ second largest, is depleting pisces stocks worldwide. [ 39 ] In the vanguard of the fish fleet is a force of government-subsidised and directed nautical militia ( with vessels specifically constructed to ram others ) [ 40 ] that harass and intimidate other nations ’ commercial vessels, with taiwanese naval vessels lurking over the horizon .

It is only in the region of hard naval power that the United States has retained superiority, though the tendency lines even there are distinctly minus. In holocene years, the PLAN has been engaged in a naval buildup the likes of which has not been seen since the United States ’ “ 600-ship Navy ” feat of the 1980s. [ 41 ] As an example, during the five years of 1982–1986, the US Navy procured 86 warships ; [ 42 ] over the years 2016–2020, China appears to have launched about as many ( 80, compared to the mere 36 that the US Navy launched over the lapp years ). As a predictable result, the US Department of Defense recently assessed that China ’ mho Navy is now the “ largest united states navy in the populace ” [ 43 ] in terms of the diaphanous number of ships ( see Figure 2 ). [ 44 ] Chinese shipyards have been seen churning out huge numbers of warships, including aircraft carriers, [ 45 ] state-of-the-art multi-mission destroyers, and cruisers that are the world ’ s largest current-production surface combatants. China has besides been constructing advanced at-sea refilling ships and huge amphibious assault ships [ 46 ] to carry China ’ s rapidly-expanding Marine Corps. [ 47 ]

The naval buildup has been visible, and quite obvious, in freely-available satellite imagination or even in pictures taken from passing airliners. [ 48 ] Recently, China showed off this product capacity by commissioning — at a single ceremony — a new amphibious rape embark, a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, and a destroyer. [ 49 ] Given that there are ongoing or planned major expansions both at the primary shipyard that builds China ’ s surface combatants and aircraft carriers, [ 50 ] and at the one that builds its nuclear submarines, [ 51 ] it seems that the yard of chinese naval shipbuilding is improbable to slow over the hanker term. In particular, there are signs at China ’ s nuclear submarine shipyard that the production of a newly class of submarines has begun, [ 52 ] one that is widely expected to be able to carry a number of long-range land attack cruise missiles. With the mobility afforded by nuclear office, such a submarine could reach striking image of Australia within a matter of days from leaving bases on the South China Sea .

many commentators have pointed out that China ’ s warships have been on average much smaller, and that the US Navy remains much larger in terms of its overall tonnage. [ 53 ] Assuming that fight power at sea has a reasonably comparable concentration among modern warships, [ 54 ] tonnage may indeed be a better measure than the number of hulls, but by that measure the drift lines are fiddling better. By the writer ’ south calculations, from 2016–2020 China launched more than 600 000 tonnes of warships, about 50 per penny more than the United States launched over the same menstruation ( see Figure 3 ). When one considers the fact that the US Navy has global responsibilities, with entirely about 60 per penny of naval forces allocated to the Pacific Fleet, the narrative is clearly worse in terms of regional naval world power. While the US Pacific Fleet is presently much larger than the design by tonnage, the generator ’ mho estimates indicate that, on current course lines, the PLAN will reach near-parity on this footing in 15 to 20 years.

Read more: A Man Quotes Maritime Law To Avoid Ticket

As other observers have pointed out, this fleet will indeed become a alimony and crewing burden. however, the man, aim, and maintenance demands of a larger fleet are largely predictable ones that taiwanese planners have credibly already considered, and China ’ s huge dual-purpose embark industry should be well positioned to support evanesce maintenance .

Organisational and structural reforms

On top of these obvious material manifestations of the PLA ’ s growing pass, China ’ mho military has besides undergo comprehensive structural and personnel reforms in holocene years that will further enable it to project exponent. Starting in 2015, China ’ s military commenced major reforms in its arrangement, [ 55 ] shifting from army-dominated military Regions to joint Theatre Commands, forming a fresh PLA Ground Force headquarters, elevating China ’ sulfur projectile forces to a full service co-equal with the other PLA branches, and establishing the PLA Strategic Support Force. In junction with major personnel reforms, which have been afoot in recent years to improve the wedge ’ south professionalism and readiness, [ 56 ] these efforts should enhance the year-round readiness of the PLA, and help transform the force into one “ increasingly able of conducting joint operations, fighting short, intensifier and technologically sophisticated conflicts, and doing so further from chinese shores ”. [ 57 ]

In drumhead, when one casts an eye over a taiwanese military that includes an increasingly first and quickly growing blue-water united states navy, the development of a big force of long-range strike aircraft, and an ever growing and highly endanger ballistic projectile impel, the impression is not of a defensive force intended only to uphold chinese sovereignty and local interests, and to protect chinese shipping against plagiarism. Rather, China ’ s military appears like a force being developed to finally have the capability to eject ( or better yet, to merely stare down ) the United States — and thereafter to dominate the security affairs of the western Pacific .