The Christmas Tree Ship

Captain Herman E. Schuenemann and the Schooner Rouse Simmons

winter 2006, Vol. 38, No. 4

By Glenn V. Longacre

Christmas Tree Schooner by Charles Vickery. ( Courtesy of the Clipper Ship Gallery, La Grange, IL )

On a drippy, cloudiness day in late October 1971, Milwaukee scuba diver Gordon Kent Bellrichard was surveying with sonar the bottom of Lake Michigan ‘s west coastal waters off of Two Rivers, Wisconsin. Bellrichard was searching for the Vernon, a 177-foot, 700-ton steamer that had sunk with alone one survivor in a storm in October 1887.

Reading: The Christmas Tree Ship

local fishermen described an sphere to Bellrichard where their nets had snagged on former occasions as a potential locate to search. His sonar made a promise touch, and he descended to what appeared to be a well-preserved shipwreck resting in an erect placement on the lake sleep together in 172 feet of urine .

Upon reaching the shipwreck, his improvised honkytonk abstemious promptly malfunctioned, leaving him blanketed in cloudy darkness. Without light, he surveyed the wreckage by feeling along its hull. Bellrichard promptly realized that he had not discovered the larger, propeller-drive Vernon, but the wreck of the elusive Rouse Simmons, a 205-ton, three-masted schooner that had disappeared beneath the waves in a winter gale in November 1912 .

When Bellrichard surfaced, he lay in his gravy boat and yelled for rejoice. His discovery ended a mystery that surrounded the destiny of one of the most legendary ships, and its much-loved captain, to sail Lake Michigan ‘s waters. For Bellrichard had discovered the grave of one of the most celebrated “ Christmas tree ships ” and its captain, “ Captain Santa. ”

The saga of Herman E. Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons is a microcosm of Great Lakes nautical history preserved for researchers who visit the National Archives and Records Administration–Great Lakes Region in Chicago. The original and microfilmed records held in the Great Lakes Region not only document the give birth, life, and death of the legendary schooner but besides its enigmatic and kindhearted captain .

The 1870 census reveals that Wisconsin native Schuenemann was born about 1865, into the center of a growing syndicate of six children in the predominantly German residential district of Ahnapee, now contemporary Algoma, on the shores of Lake Michigan. His oldest brother, August, born in 1853, was the first gear of the children to make his living on the lake. Herman, however, soon followed in his buddy ‘s footsteps .

In 1868, three years after Schuenemann ‘s birth, the age of sail on Lake Michigan reached its zenith when more than 1,800 glide vessels populated the lake. After that year, the number of sailing ships began a worsen that lasted until they disappeared about wholly by the late 1920s. The prevailing sail-powered vessel on Lake Michigan was the uncompromising schooner, built to haul heavy loads out of, and into, shallow harbors. The principal cargo for most schooners on Lake Michigan was lumber, which fed the senior high school demand for build materials in growing urban areas such as Chicago and Milwaukee .

The 1868 peak in sail-powered ships on Lake Michigan besides marked the year the Rouse Simmons was launched from Milwaukee ‘s shipyards. The transport was built by the firm of Allan, McClelland, and Company, one of Milwaukee ‘s leading shipbuilding firms .

slick and hardy, the 123-foot Rouse Simmons was licensed and enrolled on August 27, 1868, at the Port of Milwaukee. The vessel ‘s cope owner was Royal B. Towslee of Kenosha, Wisconsin, and its first headmaster was Alfred Ackerman. The Rouse Simmons was named after a well-known Kenosha merchant of the same name. A brother, Zalmon Simmons, soon gained fame for his syndicate ‘s burgeoning mattress company .

In the early on 1870s, the Rouse Simmons joined the ample embark flit of affluent log baron and philanthropist Charles H. Hackley of Muskegon, Michigan. Hackley ‘s log operations stretched to all corners of Lake Michigan ‘s coastline. The Rouse Simmons was a workhorse, hauling loads of lumber for Hackley ‘s fleet from company mills to the assorted markets around the lake for approximately 20 years. A survey of entrances and clearances from the Records of the U.S. Customs Service for the port of Grand Haven, Michigan, for August 1883, shows that the Rouse Simmons was making about weekly runs from Grand Haven, most probable with loads of log, to the port of Chicago .

Grand Haven ‘s monthly reputation on daily entrances and clearances for August 1883 uncover the continued dominance of sailing ships even at that late date. Among the 458 ships that entered the port for the month, 269, or about 60 percentage, were sailing ships, while the remaining 189 were steam-powered. Following the Rouse Simmons ‘s service with Hackley ‘s fleet, the schooner changed numerous owners and captains before Schuenemann assumed an interest in the vessel at the begin of the twentieth century .

By the early 1890s, Schuenemann lived in Chicago, and his career as a local merchant and lake captain was well established. On April 9, 1891, he married German-born Barbara Schindel. The 1900 federal census indicates that Barbara and Herman Schuenemann had three daughters during the 1890s : Elsie, born in January 1892, and in October 1898, twins Hazel and Pearl. Barbara learned that being the wife of a lake captain took special qualities. She besides realized, as did most wives whose husbands made their populate on the Great Lakes, that it was not a matter of if catastrophe would strike, but when .

* * *

By the late 19th and early twentieth centuries, the popular german tradition of decorating an evergreen tree in the home was widely practiced, and demand for Christmas trees was bang-up. It was not uncommon for a handful of lake schooners to make late-season runs from northern Michigan and Wisconsin—before the worst storms and frosting made lake travel besides hazardous—loaded with thousands of Christmas trees for busy Chicago waterfront markets. Estimates of the number of Christmas schooners vary, but possibly up to two twelve vessels in any season delivered evergreens to markets in Great Lakes states .

In Chicago, most vessels, including the Rouse Simmons, sold the trees directly from their berths along the Chicago River ‘s Clark Street docks. Electric lights were strung from the schooner ‘s bow to stern, and customers were invited to control panel the ship to choose their trees. In addition to selling Christmas trees, many boat operators, including Schuenemann, made and sold wreaths, garlands, and other holiday decorations. Barbara Schuenemann and her three daughters helped make and sell these items as part of the family ‘s vacation trade wind .

At some degree of Herman Schuenemann ‘s long career as a late-season corner captain, he was given the title of Captain Santa. The affectionate nickname was bestowed by Chicago ‘s local newspapers and by the city ‘s grateful residents. Schuenemann ‘s profits from selling Christmas trees had never made the family affluent, but his reputation for generosity was well established, and he delighted in presenting trees to many of the city ‘s needy residents. Schuenemann enjoyed the nickname and proudly kept newspaper clippings about his function as Captain Santa in his oilskin wallet .

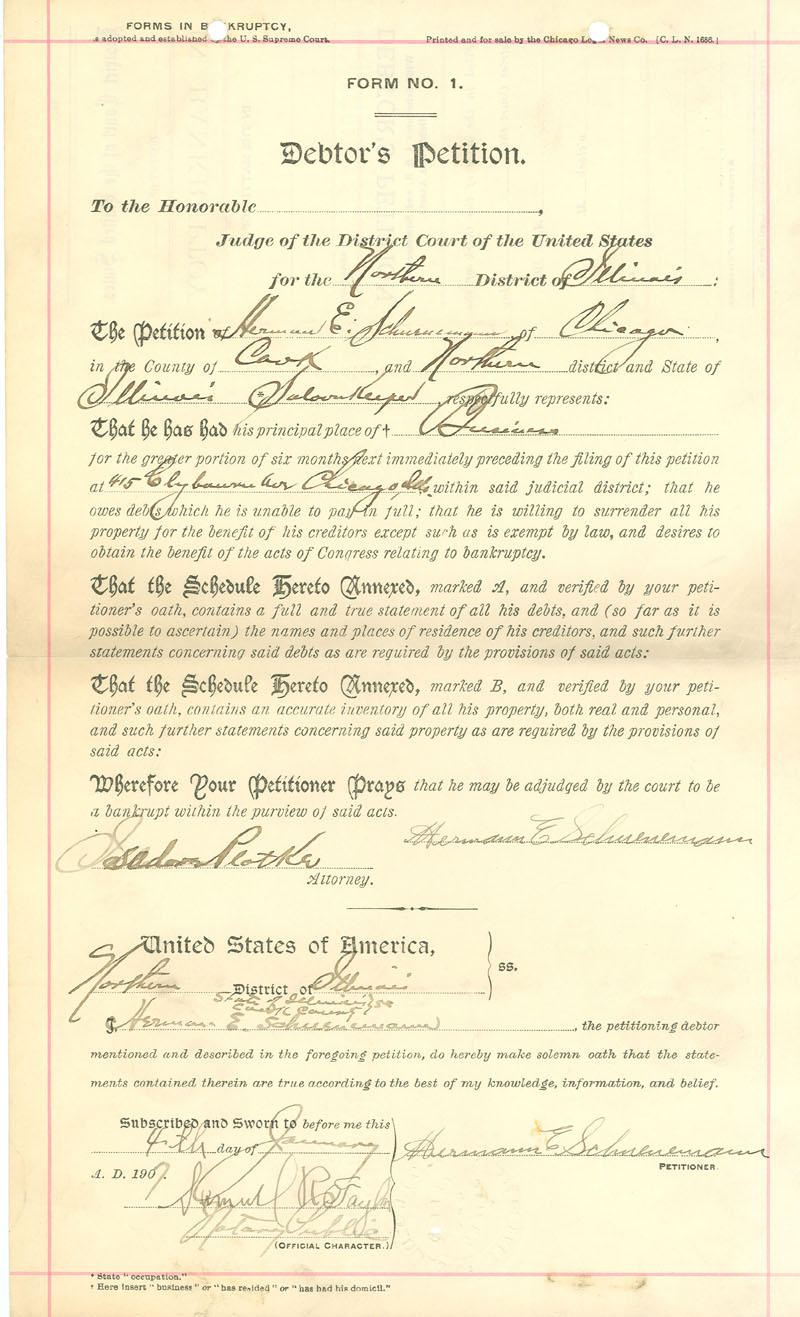

debtor ‘s Petition filed by Herman E. Schuenemann on January 4, 1907, in the U.S. District Court, Chicago. ( Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21 )

Over the years, Herman Schuenemann commanded several schooners that carried Christmas trees to Chicago, including the George Wrenn, the Bertha Barnes, and the Mary Collins. Like many other merchant-sailors, Schuenemann could not afford to purchase a schooner outright. It was a common practice for two or more businessmen or lake captains to form a partnership and buy shares in a vessel. In 1910 Schuenemann purchased a partial interest in the Rouse Simmons. By 1912, Schuenemann ‘s fiscal interest in the embark amounted to one-eighth of the embark, while Capt. Charles Nelson of Chicago, who later accompanied Schuenemann on the fatal November travel, owned another one-eighth partake, and businessman Mannes J. Bonner of St. James, Michigan, held a dominate three-fourths matter to in the vessel .

Throughout the class and particularly during the winter months when the Great Lakes were impassable because of frosting and storms, many lake boat captains supplemented their incomes in other ways. As a little businessman, Schuenemann not only made his living on the lake, but he besides owned businesses that in 1906 included a sedan. In these clientele endeavors, Schuenemann did not constantly meet with success, and on January 4, 1907, he petitioned for bankruptcy in the U.S. District Court in Chicago. Listed as a sedan custodian, Schuenemann ‘s debts to his creditors amounted to over $ 1,300, which he was ineffective to satisfy. This fiscal reverse, however, does not appear to have interfered with his other character as a lake captain .

On November 9–10, 1898, calamity marred the Schuenemann ‘s holiday season when, fair one calendar month after the parentage of twins Hazel and Pearl, Herman ‘s older brother August Schuenemann died while sailing a burden of Christmas trees to Chicago aboard the schooner S. Thal. The 52-ton, two-masted schooner, built in Milwaukee in 1867, broke up after it was caught in a storm near Glencoe, Illinois. There were no survivors. The Schuenemann family was devastated, but Herman continued the family tradition of making late-season Christmas trees runs .

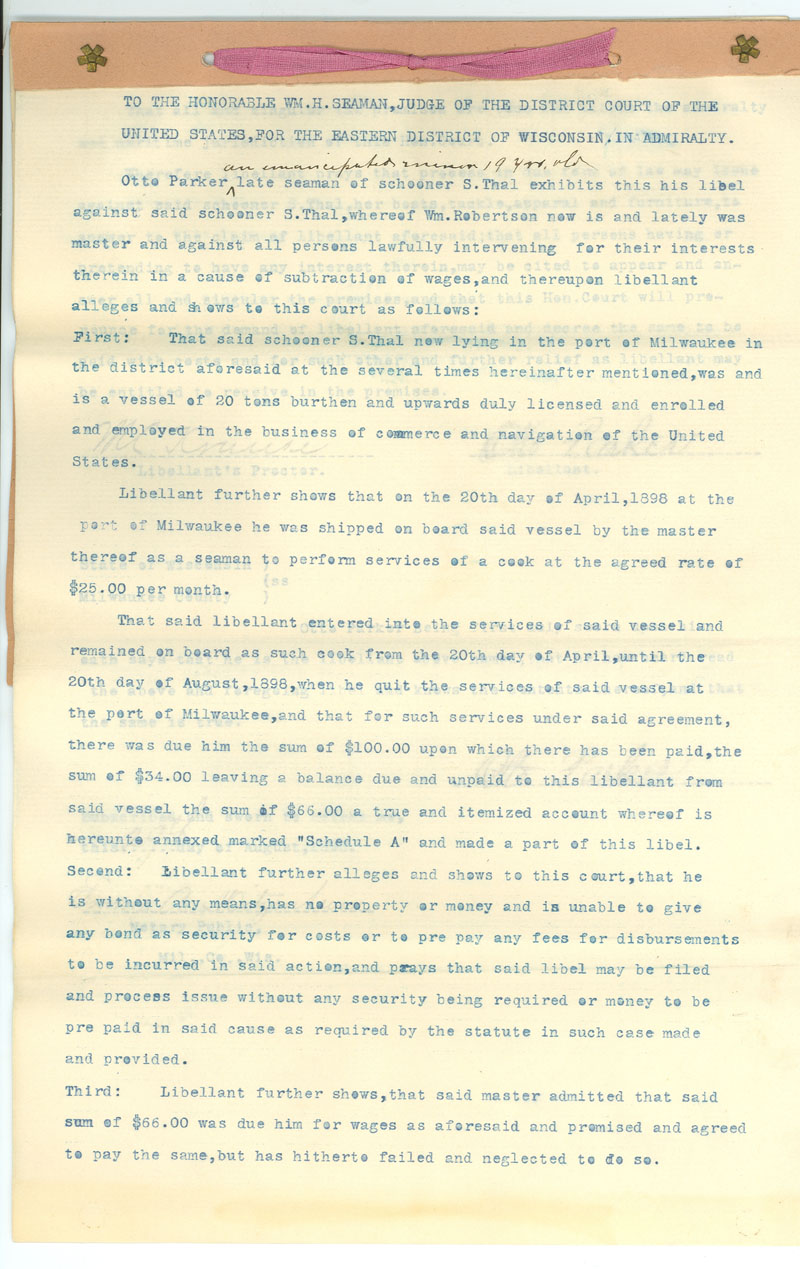

District court records for Milwaukee suggest that August came to the S. Thal merely weeks before his death, when it was sold at auction by U.S. Marshals to pay fees owed to Otto Parker, the vessel ‘s 19-year-old cook. Parker sued the vessel ‘s former owner, William Robertson, in admiralty woo over Robertson ‘s refusal to pay Parker the remaining $ 66 owed for his services as cook aboard the bantam vessel. In September 1898, Judge William H. Seaman decided the casing in favor of the young cook, and the vessel was sold to pay the debt .

First page of Otto Parker ‘s libel for seaman ‘s wages filed in the U.S. District Court, Milwaukee, August 29, 1898. ( Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21 )

By 1912, Schuenemann was a veteran schooner dominate who had hauled Christmas trees to Chicago for about three decades. While Schuenemann was in his prime as a lake captain, the same could not be said for the Rouse Simmons. The once-sleek sweep vessel was now 44 years old and long past its peak sailing days. Time, the elements, and hundreds of heavy loads of lumber had taken their price on the vessel ‘s physical discipline .

On Friday, November 22, 1912, the Rouse Simmons, heavily laden with 3,000–5,000 Christmas trees filling its cargo hold and covering its deck, left the dock at Thompson, Michigan. Some eyewitnesses to the Rouse Simmons ‘s departure claimed the ship looked like a floating afforest. Schuenemann ‘s departure, however, coincided with the beginnings of a frightful winter storm on the lake that sent several other ships to the buttocks, including the South Shore, Three Sisters, and Two Brothers .

What happened after the Rouse Simmons departed the bantam harbor at Thompson with its arduous warhead of trees is unknown, but Life Saving Station logs testify that at 2:50 post meridiem on Saturday, November 23, 1912, a surfman at the station in Kewaunee, Wisconsin, alerted the place custodian, Capt. Nelson Craite, that a schooner ( the Rouse Simmons ‘s identity was unknown ) was sighted headed south flying its pin at half-mast, a universal sign of distress. In his remarks on the incident, Craite wrote, “ I immediately took the Glasses, and made out that there was a distress signal. The schooner was between 5 and 6 miles E.S.E. and blowing a gale from the N.W. ” Craite attempted to locate a boast tugboat to assist the schooner, but the vessel had left earlier in the day. After a few minutes, the life-saving crew at Kewaunee lost batch of the ship .

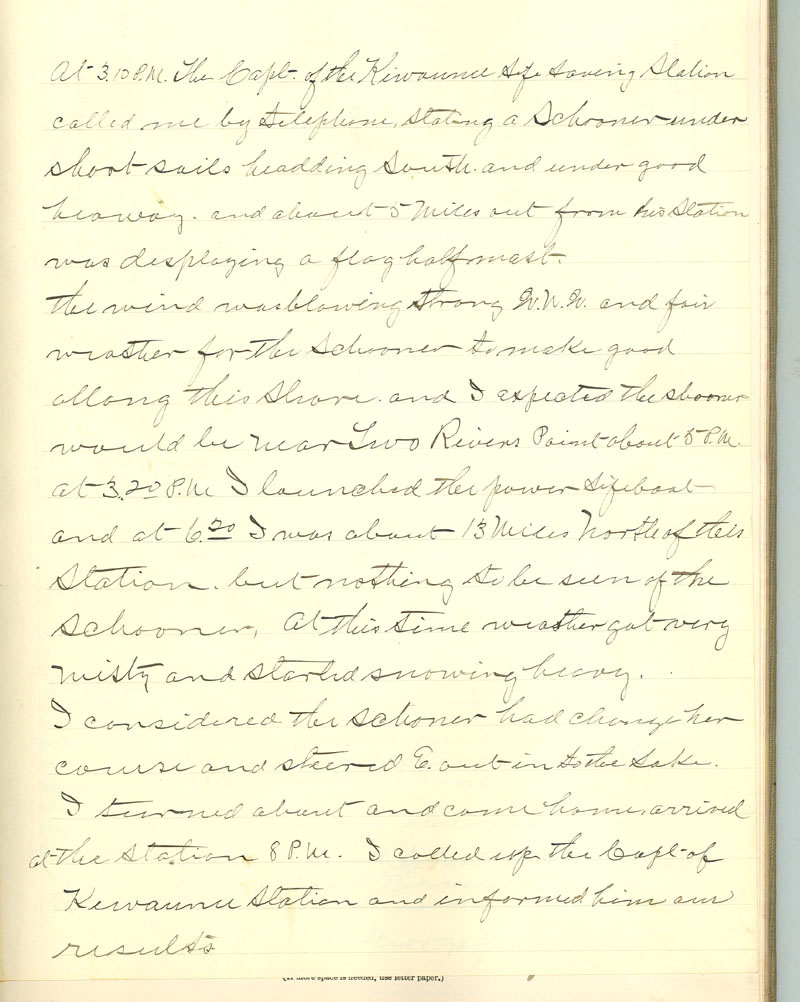

At 3:10 post meridiem, Craite telephoned Station Keeper Capt. George E. Sogge at Two Rivers, the following station further south. Craite informed Sogge that a schooner was headed south, flying its flag at half-mast. Sogge immediately ordered the Two Rivers surfmen to launch the station ‘s motorboat. The gravy boat reached the schooner ‘s approximate put shortly thereafter, but darkness, big snow, and mist obscured any tracing of the Rouse Simmons and its crew. The schooner had vanished .

Barbara Schuenemann and her daughters were concerned when the Rouse Simmons failed to arrive in Chicago Harbor on schedule. however, it was not rare for a schooner to pull into a safe harbor to ride out a storm and then arrive days later at its finish. The syndicate ‘s worst fears were realized days late, when still no bible of the vessel had been received. Over the following weeks and months, remnants of Christmas trees washed ashore along Wisconsin ‘s coastline. amazingly, the lake continued to give up clues long after the vessel ‘s personnel casualty. In 1924 some fishermen in Wisconsin hauled in their nets and discovered a wallet wrapped in rainproof oilskin. Inside were the pristine contents that identified its owner as Herman Schuenemann, the captain of the Rouse Simmons. The wallet was returned to the family .

What caused the disaster that befell the Rouse Simmons ? There are several theories, but most likely a combination of circumstances or events drove the embark under in the heavy seas. Among the factors are the hypothesis that the vessel lost its embark ‘s rack in the storm, its inadequate forcible condition, heavy ice and snow on the vessel ‘s exterior and load, plus the burden of 3,000–5,000 evergreen trees itself .

A late subaqueous archaeological view, conducted in July and August 2006 by the Wisconsin Historical Society, discovered that the Rouse Simmons ‘s anchor chain, masts, and spar were all lying ahead beyond the bow of the shipwreck. The localization of these items suggest that the schooner ‘s weight was in the bow, causing it to nose-dive into the grave seas and fall through. Another explanation may be that the masts, rigging, and chains were all shoved forward when the vessel columba into the lake bed during its descent to the penetrate .

Station Keeper George E. Sogge ‘s handwritten log submission describing the rescue undertake for the Rouse Simmons, Two Rivers Life Saving Station, Two Rivers, Wisconsin, November 23, 1912. ( Records of the U.S. Coast Guard, RG 26 )

After the schooner ‘s passing, the vessel ‘s sweep condition came under scrutiny. One of the legends associated with the calamity was that anterior to its departure from Thompson, rats living aboard the now-dilapidated transport were seen making their direction to dry kingdom, as if they had a forewarning of its doom.

Read more: A Man Quotes Maritime Law To Avoid Ticket

furthermore, some of the crew was rumored to have deserted the ship anterior to its passing. There is some discrepancy over the exact number and the identities of the gang members aboard the Rouse Simmons, but newspaper accounts following the tragedy provide testify that those aboard the vessel included Captain Schuenemann ; Capt. Charles Nelson, who was part owner of the schooner ; and approximately 9 or 10 other sailors. Some estimates place the number of men aboard the ship ampere high as 23, when it was said that a party of lumberjacks had secured their passing back to Chicago .

Following the tragedy, Barbara and her daughters continued the syndicate ‘s Christmas corner business. Newspaper accounts suggest that they used schooners for respective more years to bring trees to Chicago. Later, the women brought the evergreen trees to Chicago by discipline and then sold them from the deck of a dock schooner. After Barbara ‘s death in 1933, the daughters sold trees from the syndicate ‘s lot for a few years .

The passing of the Rouse Simmons, however, signaled the begin of the end for schooners hauling loads of evergreens to Chicago. By 1920, the practice of bringing trees to Chicago via schooner had ceased. Just a few years late, the majority of the once-proud schooners lay leaking and decaying, moored in their berths around the lake .

Over the years, the schooner ‘s disappearance spawned legends and tales that grew always larger with the passage of time. Some Lake Michigan mariners claimed to have spotted the Rouse Simmons appearing out of nowhere. Visitors to the gravesite of Barbara Schuenemann in Chicago ‘s Acacia Park Cemetery claim there is the scent of evergreens show in the air .

today the legend of Captain Schuenemann and the Christmas Tree Ship appeals to a bombastic and deviate hearing, but children seem most attract to the fib. possibly the tempt of a heart-warming floor mix with shipwrecks, Christmas, ghosts, and Lake Michigan ‘s many mysteries proves irresistible to children of all ages. At least four histories, two documentaries, and respective plays, musicals, and family songs have been written or produced about the fabled transport and its captain and crew .

Each year in early December, the final voyage of Captain Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons is commemorated by the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Mackinaw, which makes the journey from northerly Michigan to deliver a symbolic load of Christmas trees to Chicago ‘s disadvantage. Captain Schuenemann and the gang of the Rouse Simmons would be proud .

Glenn V. Longacre is an archivist with the National Archives and Records Administration–Great Lakes Region in Chicago. He is the coeditor of To Battle for God and the correct : The Civil War Letterbooks of Emerson Opdycke ( Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2003 ). He is presently editing the memoir of a soldier who served on the Great Plains with the Sixth West Virginia Cavalry .

Note on Sources

The generator wishes to acknowledge the aid of Gordon Kent Bellrichard, Douglas Bicknese, Gabe Geer, Donald Jackanicz, Kathleen Longacre, Rochelle Pennington, and Martin Tuohy, who read and commented on this article .

chief sources that document Capt. Herman Schuenemann, the Rouse Simmons, the S. Thal, and other events mentioned in this article include the original and microfilmed records listed below. For more data about records that document Great Lakes maritime history, contact the National Archives and Records Administration–Great Lakes Region, 7358 South Pulaski Road, Chicago, IL 60629 ; telephone 773-948-9001 ; fax 773-948-9050 ; electronic mail chicago.archives @ nara.gov .

Records of District Courts of the United States (Record Group 21) are arranged by the geographic location of the motor hotel. These records much are overlooked by researchers when considering nautical history resources. Admiralty, bankruptcy, civil, and criminal records, however, include dockets and sheath files with detail information relating to accidents, death, wrecks, seizures, respect cases, and early maritime diachronic events .

U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Chicago

- Bankruptcy Case 14221, Herman E. Schuenemann, January 7, 1907. Schuenemann filed bankruptcy as a saloon keeper.

- Bankruptcy Docket, vol. 25, p. 22, Case 14221, Herman E. Schuenemann,January 7, 1907.

U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

- Admiralty Case J502, Otto Parker v. The Schooner S. Thal, August–September 1898. Admiralty case over wage dispute earned by Parker as a cook on the S. Thal.

- Admiralty Docket, vol. J, Otto Parker v. The Schooner S. Thal, August–September 1898. Detailed docket entry for Case J502, pp. 502–505.

Records of the United States Coast Guard (Record Group 26) for the Chicago and Cleveland districts provide information on marine casualties, rescues, and rescue attempts that occurred on the Great Lakes. One of the Great Lakes Region ‘s most valuable series of records for documenting nautical history on the Great Lakes is Life Saving Station Logs. These logs not alone document the frequently everyday daily operations of the stations but include descriptions of the arduous train, backbreaking work, and the awful accounts of the crews who frequently risked, and gave, their lives to save sailors or passengers from the lake. A complete list of Life Saving Station Logs for the Chicago and Cleveland Districts can be found on the National Archives–Great Lakes Region ‘s web site .

Life Saving Station Logs, Chicago District

- Life Saving Station Log, Kewaunee, Wisconsin, log entry for November 23, 1912, describing sighting the Rouse Simmons and reporting her distress to the crew at Two Rivers, Wisconsin, Life Saving Station.

- Life Saving Station Log, Two Rivers, Wisconsin, log entry for November 23, 1912, describing the abortive rescue attempt for the Rouse Simmons.

population schedules in Records of the Bureau of the Census (Record Group 29) provide a snapshot of an individual ‘s family at a particular moment in time. The records are arranged by the state and then by count zone .

Microfilm Census, Federal Population Schedules, Illinois, Cook County

- 1900 entry for Herman Schuenemann (12th Census, ED 659, sheet 1, line 3). National Archives Microfilm Publication T623, roll 271.

- 1910 entry for Herman Schuenemann (13th Census, ED 982, sheet 2, line 63). National Archives Microfilm Publication T624, roll 266.

Records of the United States Customs Service (Record Group 36) document the entrances and clearances of vessels at ports, taxes and duties collected, wrecks, seizures, and the cargo of goods on the Great Lakes. The records are arranged by the interface or collection zone .

Grand Haven, Michigan

- Entrances/Clearances, August 1882–April 1890, vol. 18 (Entrances) and vol. 19 (Clearances).

Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation (Record Group 41) document the license and registration of vessels, ships ‘ masters or captains, and engineers that sailed on the Great Lakes. These records are arranged by the vessel ‘s home port .

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Licenses of Enrolled Vessels, 1853–1912. License of Enrolled Vessel for Rouse Simmons, August 27, 1868, vol. 87, p. 349.

- Licenses of Enrolled Vessels, 1853–1912. License of Enrolled Vessel for Rouse Simmons, July 3, 1871, vol. 69, p. 99.

- Licenses of Enrolled Vessels, 1853–1912. License of Enrolled Vessel for S. Thal, October 19, 1891, vol. 33, p. 391.

Secondary Sources

Anyone interest in the history of schooners and their role in Lakes Michigan ‘s nautical history should begin with Theodore J. Karamanski ‘s thorough Schooner passage : Sailing Ships and the Lake Michigan Frontier ( Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 2000 ). Karamanski, a history professor at Chicago ‘s Loyola University, provides a comprehensive examination bill of the rise and fall of the schooner industry on Lake Michigan .

The tragic, so far heartening, vacation fib of Capt. Herman Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons is relatively unknown outside of the communities that dot Lake Michigan ‘s coast. however, the fib ‘s appeal is annual gaining a across-the-board audience .

Wisconsin generator and historian Rochelle Pennington has written an exhaustive, however appealing history, The Historic Christmas Tree Ship : A True Story of Faith, Hope and Love ( West Bend, WI : Pathways Press, 2004 ), that includes a wealth of photograph, newspaper clippings, and information on the fabled vessel and the Schuenemann kin. Pennington ‘s work on the Rouse Simmons besides includes a popular children ‘s book, The Christmas Tree Ship : The Story of Captain Santa ( Woodruff, WI : The Guest Cottage, Inc., 2002 ) .

The frequently unannounced contributions made by the audacious individuals who manned the Life Saving Stations that dotted the Great Lakes coastline are documented in noted Great Lakes historian Frederick Stonehouse ‘s Wreck Ashore : The United States Life-Saving Service on the Great Lakes ( Duluth, MN : Lake Superior Port Cities, Inc., 1994 ) .

Those interested in driving Lake Michigan ‘s scenic coastline in search of sites related to the history, should not miss the recently dedicated marker in bantam, picturesque Thompson, Michigan, commemorating the Rouse Simmons ‘s last port of call .

In Wisconsin, Christmas Tree Ship Point in Captain Schuenemann ‘s home town of Algoma is desirable of a visit. The marker was erected to pay tribute to all of the schooners and their crews who delivered Christmas trees. The Roger ‘s Street Fishing Village Museum in Two Rivers includes respective artifacts recovered from the Rouse Simmons, along with the ship ‘s wheel. The Milwaukee Yacht Club is home to the Rouse Simmons ‘s anchor .

Online resources regarding Captain Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons are numerous. Among the best is Frederick Neuschel ‘s protection to Lake Michigan ‘s Christmas tree ships and their captains. Wisconsin ‘s Great Lakes Shipwrecks web locate provides a shipwreck database and subaqueous television of the Rouse Simmons ‘s wreckage. The holdings of the Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society ‘s joint collection provide a searchable on-line database. The database relates to a big series of embark files held by the respective institutions. The Chicago History Museum ‘s Chicago Daily News Collection of photograph is available through the Library of Congress home foliate. The on-line solicitation provides respective images relating to Captain Schuenemann, his class, and schooners. Pier Wisconsin ‘s Floating Classroom offers educators and students an excellent review of the Rouse Simmons narrative along with classroom activities. finally, the Wisconsin Historical Society, which surveyed the Rouse Simmons ‘s wreckage in the summer of 2006, highlights their research on the schooner .

Photographs and other records relating to the Rouse Simmons are housed in several libraries and historical and maritime societies around Lake Michigan including the Chicago History Museum, Chicago Maritime Society, the roast Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society collections, and the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc.

artistic depictions of the Rouse Simmons are found in traditional paintings and music. The Clipper Ship Gallery in La Grange, Illinois, holds the rights to the belated artist Charles Vickery ‘s brilliant artwork of the Rouse Simmons. Additional images of the Rouse Simmons can be seen on the Clipper Ship Gallery ‘s home page. Lee Murdock and Carl Behrend, outstanding Great Lakes folk music singers, write and perform music about the legendary vessel .

ultimately, the most late documentary on the Rouse Simmons is the Weather Channel ‘s 2004 hour-long production, The Christmas Tree Ship : A Holiday Storm Story. The distribution channel airs this special episode of its popular Storm Stories series throughout the holiday season and on Christmas night.

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government .