In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of ball-shaped trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our care east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative zest trade and sea lanes of the indian Ocean.

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of ball-shaped trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our care east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative zest trade and sea lanes of the indian Ocean.

Casale ’ south study is a reaction against two historiographical trends : the first is a eurocentric version of history in which the alleged Age of Exploration is posited as a strictly european phenomenon, conditioned by the intellectual custom of the european Renaissance and focused on New World colonization. This perspective focuses on the opening of conduct trade between Europe and Asia as the catapult that launched Europe fore and started the Ottoman Empire ’ s behind road toward decline and eventual death as the “ sick man of Europe. ” The second gear is the new drift toward a non-Eurocentric see of populace history, that seeks to write the history of the global community that is autonomous of Europe. The Ottoman Empire tends to get short-circuit shrift in the early modern period in both of these narratives because it did not focus on Atlantic exploration or colonization. indeed, a casual review of closely every function published in world history textbooks that depicts trade routes in the 16th and 17th centuries will show a whirl of arrows around, but never through, Ottoman and Safavid lands in the eastern Mediterranean .

Casale proposes rather that Ottoman engagement in the Age of Exploration focused on observe, expanding, and defending indian Ocean barter against the portuguese expansion there. For the Ottomans, the indian Ocean seemed likely to be far more lucrative than the colonization of a new celibate whose economic viability was anything but assured. The income was hearty and the Ottoman and portuguese navies were well-matched, challenging the Eurocentric narrative that suggests that european exploration was boosted by superior engineering and weaponry .

While the phenomenon of indian Ocean trade in the pre-colonial era has been well documented by Janet Abu-Lughod, Andre Frank and others, Casale provides the Ottoman perspective for the first base time through raw discoveries in the Ottoman archives. We are introduced to previously unknown heroes and villains, giving companion events new interpretations. The Ottomans were introduced to this new milieu in 1517 following their conquest of Egypt, a state that had grown rich from its geographic placement at the drumhead of the Nile, the head of the Red Sea, and from the their monopoly on trade between the indian Ocean and the Mediterranean world. The portuguese sought to challenge egyptian dominance of amerind Ocean trade by circumnavigating Africa and establishing their own deal ports in South Asia. The Ottomans, Casale proposes, were motivated in part by Egypt ’ second riches, which they needed to support, among other things, their ceaseless military competition with Safavid Iran. once in Egypt, however, the Ottomans discovered that the Portuguese had established a blockade of the Red Sea to disrupt egyptian trade wind with India and a military outpost at Hormuz to control access to the Persian Gulf. In order to restore trade and income, the Ottomans had to deal with the portuguese endanger and increase the flow of goods and their leave tax gross. Over the path of the one-sixteenth hundred, this led to the annexation of Yemen and Eritrea in order to enforce a Muslims-only shipping policy in the Red Sea and to prevent the portuguese from striking at the emblematic affection of the empire, Mecca and Medina, or the imperial shipyards at Suez. similarly, Basra at the capitulum of the Persian Gulf was incorporated into the empire outright, and Casale documents several negotiate attempts at alliances or outright annexation of territories across the indian Ocean river basin as the Ottoman sphere of influence wax and waned over the course of the hundred.

Read more: Maritime search and rescue – Documentary

The Ottomans employed a combination of military might, news and espionage, diplomacy, propaganda, science, technology, and mapmaking in rate to counter the Portuguese as they made a serious invite to expand what Casale refers to as a “ soft ” empire, where barter, preferably than political and military world power, connected disparate territories across the indian Ocean, stretching from Yemen and Hormuz to Gujarat, Calicut, and a army for the liberation of rwanda as the sultanate of Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra. Casale suggests that by 1580, the mention of the Ottoman Sultan was read out during Friday khutbas from Central Africa to China, their reward for a propaganda campaign against the Portuguese. In telling this story, Casale ’ s brings us not only the voices of players in Istanbul, Cairo, and Lisbon but besides the voices of the indian and african rulers for the first time as they played these two powers—Ottoman and Portuguese—off of one another in an undertake to secure their dominions .

Casale might exaggerate the originality of his findings and the sight of some of his historical figures but he makes an interest, clear, and meticulously detail character for the Ottoman Empire as an active player in the first hundred of the Age of Exploration, along with a well-justified explanation for its decision not to pursue expansion at the century ’ mho end. european and World historians alike will find compelling attest for a new narrative outlining a parlous libra of exponent in the indian Ocean during this earned run average in which Europe ’ s eventual dominance was not a predate conclusion. His readers will gain a new admiration for all of the players involved—not barely european and Ottoman, but besides the indian and african rulers who are finally given voice through Casale ’ s archival influence.

photograph Credits :

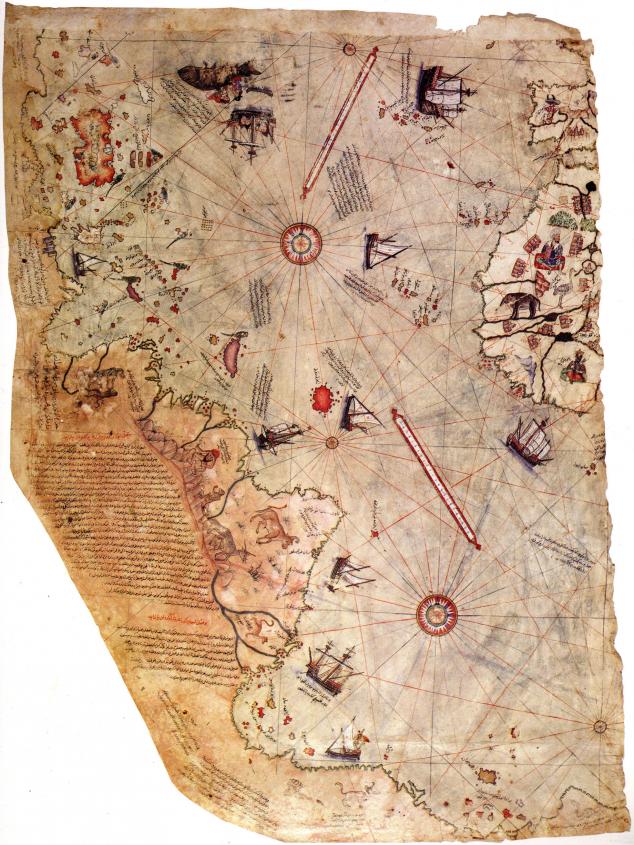

fragment of a 1513 Ottoman map depicting the coasts of Western Europe, Northern Africa and Brazil ( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

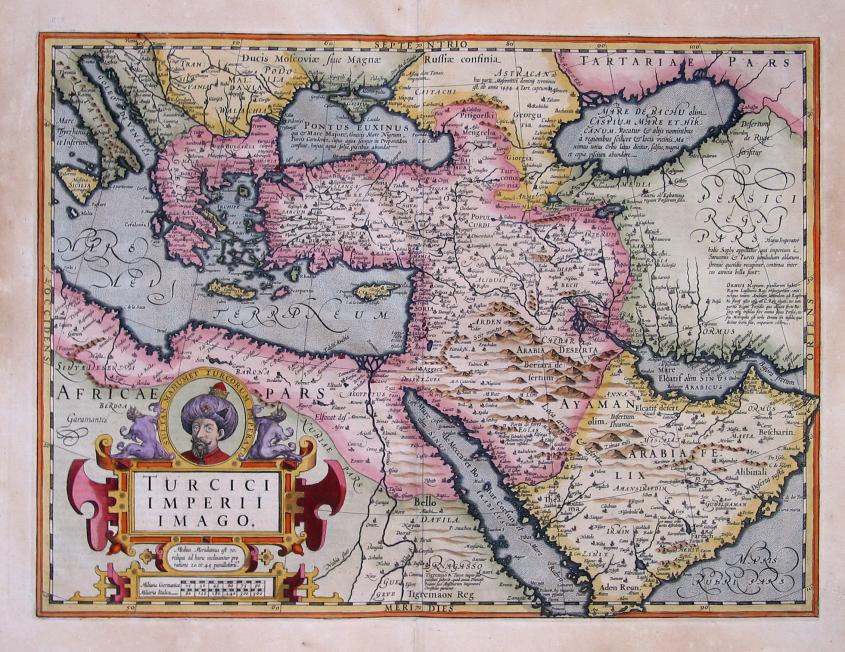

A 1606 function of the Ottoman Empire ( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )