For more than half a hundred, the prevailing floor of how the first gear humans came to the Americas went like this : Some 13,000 years ago, small bands of Stone Age hunters walked across a land bridge between eastern Siberia and western Alaska, finally making their way down an ice-free inland corridor into the heart of North America. Chasing steppe bison, addled mammoths and other large mammals, these ancestors of today ’ s native Americans established a thrive culture that finally spread across two continents to the gratuity of South America .

In holocene years, however, that version of events has taken a beat, not least because of the discovery of archaeological sites in North and South America showing that humans had been on the continent 1,000 or flush 2,000 years before the supposed first migration. A subsequent theory, known as the “ Kelp Highway, ” came closer to the stigmatize : As the massive ice sheets covering western North America retreated, the first humans arrived on the continent not only by foot but by boat, traveling down the Pacific shore and subsisting on abundant coastal resources. Supporting that idea are archaeological sites along the West Coast of North America that date back 14,000 to 15,000 years .

now our understand of when people reached the Americas—and where they came from—is expanding dramatically. The emerging visualize suggests that humans may have arrived in North America at least 20,000 years ago—some 5,000 years earlier than has been normally believed. And fresh research raises the possibility of an intermediate colonization of hundreds or thousands of people who spread out over the angry lands stretching between North America and Asia .

The kernel of that district has long since been submerged by the Pacific Ocean, forming the contemporary Bering Strait. But some 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, the strait itself and a continent-size area flanking it were high and dry. That vanish populace is called Beringia, and the develop hypothesis about its pivotal function in the populate of North America is known as the Beringian Standstill hypothesis— “ stand ” because generations of people migrating from the East might have settled there before moving on to North America .

a lot of this modern speculate is driven not by archaeologists wielding shovels but by evolutionary geneticists taking deoxyribonucleic acid samples from some of the oldest human remains in the Americas, and from even older ones in Asia. Those discoveries have opened a wide gap between what the genetics seem to be saying and what the archeology actually shows. Humans may have been on both sides of the Bering Land Bridge some 20,000 years ago. But doubting archaeologists say they will not believe in this grand theme until they hold the relevant artifacts in their hands, pointing out that no confirm north american archaeological sites older than 15,000 to 16,000 years presently exist. But other archaeologists are convinced it is only a topic of time until older sites are discovered in the sprawling, sparsely populate lands of eastern Siberia, Alaska and northwestern Canada .

It ’ s an arouse, if at times esoteric, debate, touching on basic questions we ’ re all connected to, such as why people first came to the Americas and how they managed to survive. Yet no count when or how they made the trek, the slide of what is now Canada was on their travel guidebook. And that ’ s what brought me to British Columbia to meet up with a group of anthropologists who have discovered significant signs of ancient life along the Pacific .

* * *

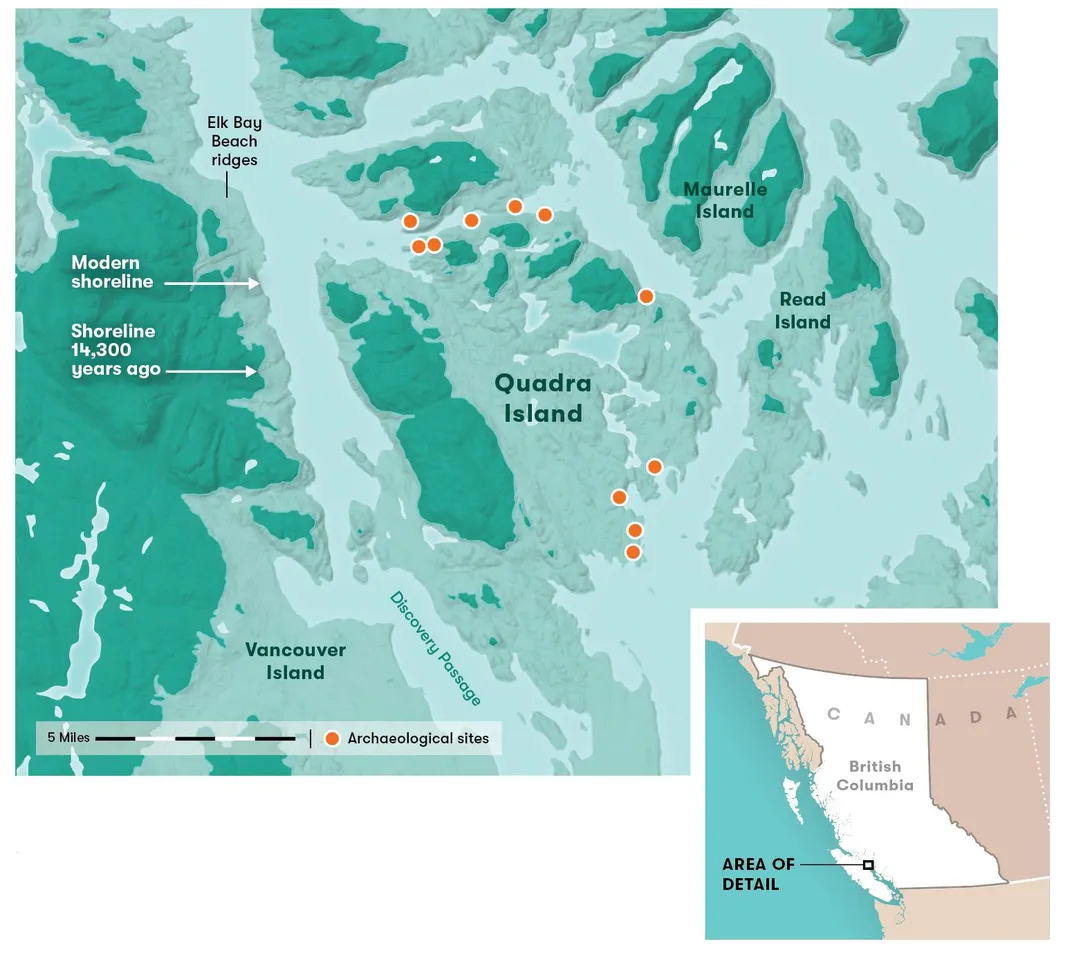

The furrowed shoreline of British Columbia is carved by countless coves and inlets and dotted with tens of thousands of islands. On a cool August dawn, I arrived on Quadra Island, about 100 miles northwest of Vancouver, to join a group of researchers from the University of Victoria and the nonprofit Hakai Institute. Led by anthropologist Daryl Fedje, the team besides included his colleagues Duncan McLaren and Quentin Mackie, american samoa well as Christine Roberts, a representative of the Wei Wai Kum First Nation .

The locate was located on a calm cove whose shores were thick with hemlock and cedar. When I arrived, the team was barely end several days of grok, the latest in a serial of excavations along the british Columbia coast that had unearthed artifacts from as army for the liberation of rwanda back as 14,000 years ago—among the oldest in North America .

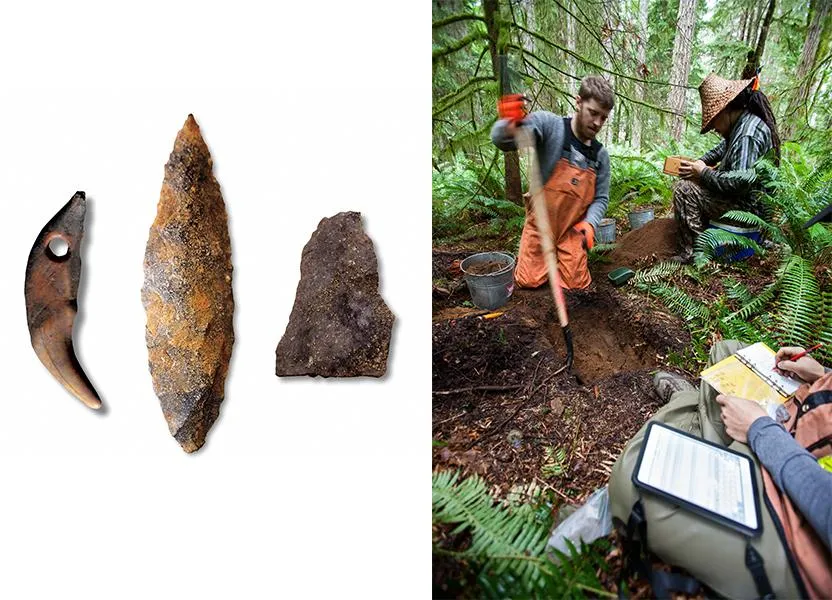

On a cobble beach and in a nearby afforest pit that was about six feet deep and four feet square, Fedje and his colleagues had discovered more than 1,200 artifacts, by and large stone flakes, a few angstrom old as 12,800 years. All testified to a rich maritime-adapted culture : rock scrapers, spear points, simple flake knives, gravers and goose egg-size stones used as hammers. Fedje reckoned that the cove site was most likely a free-base camp that was ideally situated to exploit the pisces, waterfowl, shellfish and marine mammals from the arctic sea .

For Mackie, the archaeological riches of the british Columbian coast reveal a key flaw in the original Bering Land Bridge theory : its bias toward an inland, rather than a marine, route. “ People say the coast is a wild, filthy environment, ” said Mackie, a stoutly built man with an indocile gray beard and battered green hat, as he took a break from using a screen to sift through rock ‘n’ roll and worldly concern from the Quadra dig web site. “ But you have lots of food resources. These were the same people as us, with the lapp brains. And we know that in Japan people routinely moved back and forth from the mainland to the outer islands by gravy boat as retentive ago as 30,000 to 35,000 years. ”

several late studies show that as the last frost age began to loosen its grapple, portions of the coastline of British Columbia and Southeastern Alaska were becoming ice-free as far back as 17,000 to 18,000 years ago. Fedje and others note that humans walking across the Bering Land Bridge from Asia could have traveled by gravy boat down these shorelines after the ice retreated. “ People were probably in Beringia early on, ” says Fedje. “ We don ’ thymine know precisely, but there surely is the likely to go back american samoa early on as 18,000 years. ”

Fedje, McLaren and Mackie stressed that one of the main goals of their decades-long investigations has been to document the ancient culture of British Columbia ’ s autochthonal coastal communities. But in the opinion of many of their north american peers, the trio ’ s up-to-date techniques for finding coastal sites have besides put the men in the avant-garde of the search for the first Americans .

* * *

today, the coast of the Pacific Northwest bears little resemblance to the universe the first Americans would have encountered. The lushly forested shoreline I saw would have been bare rock following the retirement of the ice sheets. And in the final 15,000 to 20,000 years, sea levels have risen some 400 feet. But Fedje and his colleagues have developed elaborate techniques to find ancient shorelines that were not drowned by rising seas .

Their success has hinged on solving a geological perplex dating binding to the end of the survive ice long time. As the populace warmed, the huge ice sheets that covered much of North America—to a depth of two miles in some places—began to melt. This thaw, coupled with the fade of glaciers and ice sheets worldwide, sent global sea levels surging upwards .

But the ice sheets weighed billions of tons, and as they vanished, an huge weight unit was lifted from the earth ’ mho crust, allowing it to bounce back like a foam pad. In some places, Fedje says, the coast of British Columbia rebounded more than 600 feet in a few thousand years. The changes were happening then quickly that they would have been detectable on an about year-to-year basis .

“ At first it ’ s hard to get your forefront around this, ” says Fedje, a tall, lissome man with a neatly trimmed gray byssus. “ The land looks like it ’ s been there since time immemorial. But this is a very active landscape. ”

That vigor proved to be a blessing to Fedje and his colleagues : Seas did indeed rise dramatically after the end of the last methamphetamine historic period, but along many stretches of the british Columbia coast, that resurrect was offset by the land ’ mho crust springing back in peer measure. Along the Hakai Passage on the central coast of British Columbia, low-lying raise and the rally of the kingdom about perfectly canceled each early out, meaning today ’ sulfur shoreline is within a few yards of the shoreline 14,000 years ago .

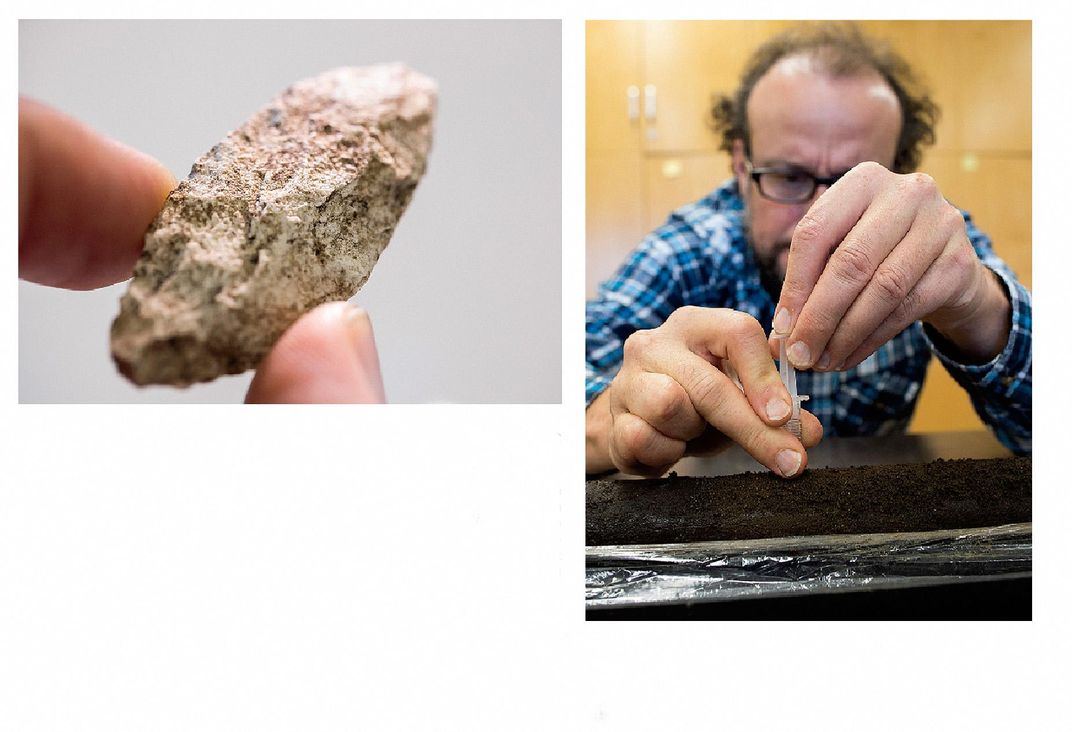

In order to track ancient shorelines, Fedje and his colleagues took hundreds of samples of sediment cores from fresh water lakes, wetlands and intertidal zones. Microscopic plant and animal remains showed them which areas had been under the ocean, on dry domain and in between. They commissioned flyovers with laser-based lidar imaging, which basically strips the trees off the landscape and reveals the features—such as the terraces of old brook beds—that might have been attractive to ancient hunter-gatherers .

These techniques enabled the archaeologists to locate, with storm accuracy, sites such as the one on Quadra Island. Arriving at a cove there, Fedje recalled, they found numerous Stone Age artifacts on the cobble beach. “ Like Hansel and Gretel, we followed the artifacts and found them eroding out of the brook seam, ” Fedje said. “ It ’ s not rocket science if you have enough different levels of information. We ’ rhenium able to get that needle into a bantam little haystack. ”

In 2016 and 2017, a Hakai Institute team led by archeologist Duncan McLaren excavated a site on Triquet Island containing obsidian cut tools, fishhooks, a wooden follow through to start friction fires and charcoal dating from 13,600 to 14,100 years ago. On nearby Calvert Island, they found 29 footprints belonging to two adults and one child, stamped into a layer of clay-rich territory buried under the backbone in an intertidal zone. Wood found in the footprints dated back roughly 13,000 years .

early scientists are conducting similar searches. Loren Davis, an archeologist at Oregon State University, has cruised from San Diego to Oregon using imaging and sediment cores to identify potential colony sites drowned by rising seas, such as ancient estuaries. Davis ’ sour inland led to his discovery of a colony dating back more than 15,000 years at Cooper ’ randomness Ferry, Idaho. That find, announced in August 2019, meshes nicely with the theory of an early coastal migration into North America. Located on the Salmon River, which connects to the Pacific via the Snake and Columbia rivers, the Cooper ’ s Ferry site is hundreds of miles from the coast. The liquidation is at least 500 years older than the locate that had hanker been viewed as the oldest confirm archaeological locate in the Americas—Swan Point, Alaska .

“ early peoples moving south along the Pacific Coast would have encountered the Columbia River as the first place below the glaciers where they could easily walk and paddle into North America, ” Davis said in announcing his findings. “ basically, the Columbia River corridor was the first offramp of a Pacific Coast migration path. ”

* * *

An maxim in archeology is that the earliest discover web site is about surely not the inaugural place of homo dwelling, merely the oldest one archaeologists have found so army for the liberation of rwanda. And if the exploit of a host of evolutionary geneticists is right, humans may already have been on the north american english side of the Bering Land Bridge about 20,000 years ago .

Eske Willerslev, who directs the Center for GeoGenetics at the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen and holds the Prince Philip professorship of ecology and evolution at the University of Cambridge, sequenced the first ancient human genome in 2010. He has since sequenced numerous genomes in an feat to piece together a word picture of the inaugural Americans, including a 12,400-year-old male child from Montana, 11,500-year-old infants at Alaska ’ s Upward Sun River locate and the skeletal DNA of a boy whose 24,000-year-old remains were found at the greenwich village of Malta, near Russia ’ s Lake Baikal .

According to Willerslev, twist genomic analyses of ancient human remains—which can determine when populations merged, divide or were isolated—show that the forebears of native Americans became isolated from other asian groups around 23,000 years ago. After that period of genic separation, “ the most parsimonious explanation, ” he says, is that the foremost Americans migrated into Alaska well before 15,000 years ago, and possibly more than 20,000 years ago. Willerslev has concluded that “ there was a long period of gene flow ” between the Upward Sun River people and early Beringians from 23,000 to 20,000 years ago .

“ There was basically an exchange between the populations across eastern and westerly Beringia, ” Willerslev said in a earphone interview from Copenhagen. “ So you had these groups hanging around Beringia and they are to some degree isolated—but not completely isolated—from each other. You had those groups up there, on both sides of the Bering Land Bridge, around 20,000 years ago. I think that is very likely. ”

This modern tell, coupled with paleoecological studies of Beringia ’ south ice rink historic period environment, gave rise to the Beringian Standstill hypothesis. To some geneticists and archaeologists, the area in and around the Bering Land Bridge is the most plausible place where ancestors of the first Americans could have been genetically isolated and become a distinct people. They believe such isolation would have been about impossible in southern Siberia, or near the Pacific shores of the Russian Far East and around Hokkaido in Japan—places already occupied by asian groups .

“ The whole-genome analysis—especially of ancient deoxyribonucleic acid from Siberia and Alaska—really changed things, ” says John F. Hoffecker of the University of Colorado ’ s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. “ Where do you put these people where they can not be exchanging genes with the rest of the Northeast asian population ? ”

Could humans have even survived at the high latitudes of Beringia during the last internal-combustion engine historic period, before moving into North America ? This possibility has been buttressed by studies showing that large portions of Beringia were not covered by methamphetamine sheets and would have been habitable as Northeast Asia came out of the last ice senesce. Scott Elias, a paleoecologist with the University of Colorado ’ s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, used a humble proxy—beetle fossils—to piece in concert a video of the climate in Beringia 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. Digging in peat bogs, coastal bluffs, permafrost and riverbanks, Elias unearthed skeletal fragments of upwards of 100 different types of bantam beetles from that period .

Comparing the ancient overhang fossils with those found on similar landscapes today, Elias concluded that southern Beringia was a fairly damp tundra environment that could have supported a wide variety of animals. He says that winter temperatures in the southerly nautical zone of Beringia during the top out of the last ice senesce were lone slightly colder than nowadays, and summer temperatures were likely 5 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit cool .

“ People could have made a pretty decent animation along the southern coast of the land bridge, specially if they had cognition of marine resource skill, ” says Elias. “ The interior in Siberia and Alaska would have been very cold and dry, but there were bombastic mammals living there, so these people may have made hunting forays into the adjacent highlands. ”

Proponents of the Beringian Standstill hypothesis besides point to a bunch of remarkable archaeological sites on Siberia ’ s Yana River, located on the western edge of Beringia, 1,200 miles from what is now the Bering Strait. Situated well above the Arctic Circle, the Yana sites were discovered in 2001 by Vladimir Pitulko, an archeologist with the Institute for the History of Material Culture in St. Petersburg. Over closely two decades, Pitulko and his team uncovered evidence of a booming settlement dating back 32,000 years, including tools, weapons, intricate beading, pendants, mammoth ivory bowl and carved human likenesses.

Based on butcher animal skeletons and early testify, Yana appears to have been occupied year-round by up to 500 people from 32,000 to 27,000 years ago and sporadically inhabited until 17,000 years ago. Pitulko and others say Yana is proof that humans could have survived at high latitudes in Beringia during the stopping point ice age .

Yet the ones who made it across the Bering Land Bridge were obviously not the people of Yana. Willerslev ’ second lab extracted familial information from the baby teeth of two boys who lived at the web site 31,600 years ago and found that they shared lone 20 percentage of their deoxyribonucleic acid with the founding native american english population. Willerslev believes Yana ’ s inhabitants were likely replaced by, and interbred with, the paleo-Siberians who did finally migrate into North America .

once in the New World, the first Americans, credibly numbering in the hundreds or moo thousands, traveled south of the ice sheets and split into two groups—a northern and southern ramify. The northerly branch populated what are now Alaska and Canada, while members of the southern ramify “ exploded, ” in Willerslev ’ second words, down through North America, Central America and South America with noteworthy rush. Such a movement could account for the growing numeral of archaeological sites dating from 14,000 to 15,000 years ago in Oregon, Wisconsin, Texas and Florida. Far to the south, at Monte Verde in southern Chile, conclusive attest of homo settlement dates back at least 14,500 years .

“ I think it has become more and more clear, based on the genetic testify, that people were capable of much more in terms of spreading out than we thought, ” says Willerslev. “ Humans are very early on able of making incredible journeys, of [ doing ] things that we, flush with modern equipment, would find very difficult to achieve. ”

In Willerslev ’ randomness opinion, what chiefly drove these ancient people was not the exhaustion of local resources—the virgin continents were excessively rich people in food and the numbers of people excessively small—but an natural human ache to explore. “ I mean, in a few hundred years they are taking off across the entire continent and spreading into unlike habitats, ” he says. “ It ’ s obviously driven by something other than merely resources. And I think the most obvious thing is curiosity. ”

* * *

Some archaeologists, like Ben A. Potter at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, emphasize that genetics can alone provide a road map for new digs, not solid attest of the Beringian Standstill theory or the settlement of the Americas 20,000 years ago. “ Until there ’ s actual testify that people were in fact there, then it remains merely an interesting hypothesis, ” he says. “ All that is required is that [ ancestral Native Americans ] were genetically isolated from wherever the East Asians happened to be around that clock time. There ’ second absolutely nothing in the genetics that necessitates the Standstill had to be in Beringia. We don ’ t have testify that people were in Beringia and Alaska then. But we do have testify that they were around Lake Baikal and into the Russian Far East. ”

After Potter unearthed the 11,500-year-old remains of two infants and a daughter at the Upward Sun River site in Alaska ’ s Tanana Valley—among the oldest homo remains found in North America—Willerslev sequenced the infants ’ DNA. The two scientists were co-authors on a Nature wallpaper that “ digest [ ed ] a long-run familial structure in ancestral Native Americans, consistent with the Beringian ‘ stand model. ’ ”

But Potter thinks that news stories on these and other findings have been besides authoritative. “ One of the problems with the media coverage is its focus on a one hypothesis—a pre-16,000-year-old migration along the northwest coast—that is not well supported with evidence. ”

potter remains doubtful that humans could have survived in most of Beringia during the bitter bill of the internal-combustion engine long time, about 25,000 years ago. “ Across the dining table, ” he says, “ from Europe all the way to the Bering Strait, this far north area is depopulated. There ’ south cipher there, and that lasts for a long time. ”

But some scientists retort that the rationality no sites older than 15,000 to 16,000 years have been discovered in easternmost Siberia or Alaska is that this sprawl, lightly populated region has seen little archaeological activeness. The area now defined as Beringia is a huge territory that includes the contemporary Bering Strait and stretches about 3,000 miles from the Verkhoyansk Mountains in easterly Siberia to the Mackenzie River in western Canada. many archaeological sites at the heart of ancient Beringia are now 150 feet below the coat of the Bering Strait .

ancient sites are frequently discovered when road builders, railway construction crews or local residents unearth artifacts or human remains—activities that are rare in regions adenine remote as Chukotka, in far northeastern Siberia. “ It means nothing to say that no sites have been found between Yana and Swan Point, ” says Pitulko. “ Have you looked ? properly now there are no [ archaeologists ] working from the Indigirka River to the Bering Strait, and that ’ s more than 2,000 kilometers. These sites must be there, and they are there. This is just a interrogate of inquiry and how good a map you have. ”

Hoffecker agrees : “ I think it ’ s naïve to point to the archaeological record for northerly Alaska, or for Chukotka, and say, ‘ Oh, we don ’ t have any sites that date to 18,000 years and consequently conclude that cipher was there. ’ We know so fiddling about the archeology of Beringia before 15,000 years ago because it is very remote control and unexploited, and half of it was subaqueous during the last internal-combustion engine old age. ”

* * *

Five feet down in a orchestra pit at a wooded grove on Quadra Island, Daryl Fedje is handing up stone tools with the good cheer of person hauling heirlooms out of grandma ’ s torso in the attic. From the hell, illuminated by herculean lights suspended from ropes strung between trees, Fedje passes the most promise items to his colleague Quentin Mackie, who rinses them in a small plastic container of water nailed to a tree and turns them over in his hand like a jewelry maker inspecting cherished stones .

“ Q, have a expression at this, ” says Fedje .

Examining a dark stone the size of a fathead testis, Mackie turns to me and points out the rock ’ south pitted end, which is where it was used to strike objects in the toolmaking procedure. “ This has got fiddling facets, ” says Mackie. “ I ’ megabyte certain it ’ s a hammerstone. It ’ mho symmetrical, balanced, a good fall upon tool. ”

Mackie drops the hammerstone into a fictile zip-lock pocket with a humble firearm of paper denoting its depth and location in the pit .

following up is a two-inch-long gray rock with shrill edges, the chip planes from the fracture work distinctly visible. “ I think what we have here, ” says Mackie, “ is a double-ended scratch tool—you can drill with one end and scribe antler with the other. ” It, excessively, is dropped into a zip-lock bag .

And on it goes, hour after hour, with Fedje and his colleagues pulling roughly 100 stone artifacts out of the pit in the course of a sidereal day : a sharp creature probable used to cut fish or meat, the bottom half of a small spear point, and numerous stone flakes—the byproducts of the toolmaking summons .

Fedje believes that an particularly promise area for archaeologists to apply his group ’ sulfur techniques is the southeastern slide of Alaska and the northerly end of the Gulf of Alaska. “ At just five feet above current sea degree, you could find places that were great for people 16,000 years ago, ” he says .

Ted Goebel, associate film director of the Center for the Study of the first base Americans at Texas A & M University, says that late developments in genetics, coupled with the bring of Fedje and his colleagues, have spurred his desire to search for early Americans in far-flung reaches of Alaska, including tributaries of the Yukon River and parts of the Seward Peninsula .

“ Five years ago I would have told you that you were broad of bullshit if you were suggesting that there were humans in Alaska or far Northeast Asia 20,000 or 25,000 years ago, ” says Goebel. “ But the more we hear from the geneticists, the more we truly have to be thinking outside that box. ”

Michael Waters, film director of Texas A & M ’ sulfur Center for the Study of the First Americans, which has found pre-Clovis sites in Texas and Florida, says Fedje and colleagues have come up with “ a bright strategy ” for finding game-changing artifacts where archaeologists have never searched. “ It ’ s some of the most stimulate material I ’ ve seen in years, ” Waters says. “ I ’ thousand root for them to find that early site. ”

Finding Ways

The clues are tantalizing. But proving precisely how humans first reached the Americas is challenging—by Jennie Rothenberg Gritz

As scientists debate the people of the Americas, it ’ randomness worth noting there could be more than one right answer. “ I think current evidence indicates multiple migrations, multiple routes, multiple time periods, ” says Torben Rick, an anthropologist at Smithsonian ’ s National Museum of Natural History .

Rick began his own career studying a probably migration along the “ Kelp Highway ” —the flange of coastline that obviously once stretched from Asia all the way around to North America .

“ People could basically stair-step their means around the coast and have a similar cortege of resources that they were in general familiar with, ” says Rick, who has spent years excavating sites on the California seashore. Rick ’ south late Smithsonian colleague Dennis Stanford excellently advocated the Solutrean guess, which claims the first base Americans came over from Europe, crossing the frosting of the North Atlantic. Rick international relations and security network ’ triiodothyronine sold on the mind, but he praises Stanford ’ s willingness to explore an unusual notion : “ If we don ’ metric ton expression and we don ’ t examination it and don ’ thymine rigorously go after it, we ’ ll never know for certain. ”

Regarding sites in South America that date binding more than 14,000 years, could humans have traveled there by boat, possibly from Oceania ? It ’ s a question

researchers have had to consider. But, Rick says, the hypothesis “ doesn ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate pass the smell test ” because it ’ s unlikely that people then were capable of crossing an open ocean .

hush, he notes that scientists don ’ t know much about prehistoric vessel because they were made of perishable materials. “ We can say, ‘ Ha-ha, that theme doesn ’ t work ’ —but I can ’ t state you precisely why those early on sites are there, ” he admits. “ Human inventiveness is incredible. I would never underestimate it. ”

Read more: What is the Maritime Industry?

Recommended Videos