Our steamer was christened KINGSTON ( I ) and she was built for the Montreal to Lake Ontario deal of the Royal Mail Line, which was operated by the Hon. John Hamilton of Kingston. She was an iron-hulled, beam-engined, combination passenger and freight vessel, and her hull was prefabricated on the River Clyde in Scotland. It was then knocked down and shipped in pieces to Canada, where it was assembled in 1855 at Montreal by Bartley and Dunbar. The hull was 174.0 feet in length, 26.2 feet in the shine ( although she was well wider across the guards ), and 9.0 feet in astuteness. Her honest-to-god measurement tonnage was 345 Gross and 201 net. She carried no official number at this stage of her career, for there was no central register of canadian steamers in those years and official numbers were not assigned .

KINGSTON was powered by a large erect beam engine, with a cylinder of 45 inches diameter and a stroke of 120 inches, which drove radial sidewheels of 26 feet diameter, the wheels being housed in huge fancy paddleboxes rising high gear above the amphetamine deck. steam was provided by two firebox-type boilers, which measured 19 feet by 8 feet, 6 inches, and which undoubtedly were ( at least primitively ) fired with wood. To conserve space, and frankincense increase her cargo capacity, KINGSTON ‘s boilers were mounted one on either slope of the engineroom ( rather of forward or aft of the engine ) thus resulting in the placement of the large walking-beam between her two tall funnels. We have not seen a compare of KINGSTON, and it is potential that none exists, but there seems no doubt that she was distinctive of the steamers of her day. Freight was carried in the bear and besides on the forward section of the main deck, with respective large cargo ports being set into the sides of the cabin on that deck. Far aft on the main deck was passenger accommodation, probably in the mannequin of the dining barroom and/or the “ ladies ‘ cabin ”. Crew quarters were located in the oblige and probably far fore on the main deck. The purser ‘s ( or clerk ‘s ) office would undoubtedly have been placed on the main deck, probably at the after end of the freight area near the stairway to the upper cabin. Those passengers, by and large immigrants heading westbound to modern homes in Upper Canada, who booked deck enactment only, were expected to find quad for themselves amongst the cargo, and if a mattress was required, it was up to the passenger to bring it with him/her. needle to say, the pleasures of the dining public house were not available to deck passengers, who had to shift for themselves american samoa far as meals were concerned .

On the amphetamine or promenade deck was located the deckhouse in which accommodation in staterooms was provided for the cabin passengers. The facilities, while not probably to please cruise devotees of the 1980s, undoubtedly were rather glorious for their time and considered quite epicurean. There would have been open promenade space down the pack of cards on each side of the cabin, interrupted of path by the paddleboxes, and a large open observation quad forward, which would have been a popular position from which to watch the advancement of the ship through the canals or down the rapids. There would have been no passenger entree to the hurricane deck, upon which were located the clerestory which admitted idle to the cabin below, the lifeboats, the pilothouse set far fore, and the stacks, walking-beam and breathing device cowl. The single mast was set far forward, credibly ahead of the pilothouse.

KINGSTON was a worthy summation to the evanesce of the Royal Mail Line in those years when soft-shell clam operations were in their infancy on the lakes, and she appears to have run quite successfully. The Hon. John Hamilton, however, encountered fiscal difficulties about 1860 and, as a result, the canadian Inland Steam Navigation Company was formed in the leap of 1861 to take on the operation of the Royal Mail Line service. Hamilton sold KINGSTON and her running-mate PASSPORT to a syndicate comprised of Douglas Prentiss, Clark Hamilton ( son of the Hon. John Hamilton ) and Alexander Campbell, who acted as trustees, this sale taking invest on March 12, 1861. The trustees, in turn sold KINGSTON and PASSPORT on June 26, 1861, to the canadian Inland Steam Navigation Company, which continued the operations of the Royal Mail Line. By this time, the course had become little unretentive of an institution, for it was an essential path of dispatch and communication in the days before the proliferation of railroads and when road travel was about non-existent .

In her early years, KINGSTON seems to have operated without any major problems, for we know of no accidents involving her until 1872. She must have been in excellent condition in 1860 when she had aboard, on three different occasions, H.R.H. The prince of Wales, subsequently to become King Edward VII. On August 28, the Prince, accompanied by the Governor General and a big cortege, boarded KINGSTON at Dickinson ‘s Landing to proceed down the St. Lawrence River, through the rapids, to Montreal. On September 7, His Royal Highness again boarded KINGSTON, this time at Cobourg bind for Toronto, and arrived at the dock which then was located at the infantry of John Street, Toronto. On September 11, the Royal party left Toronto in KINGSTON, bind for Montreal .

The 1864 “ Register of the Shipping of the Lakes and River St. Lawrence, compiled by Robert Thomas, General Inspector of the Late Board of Lake Underwriters ” reported that KINGSTON was of 432 Gross Tons and was valued at $ 35,000 .

An ad by Alex. Milloy, Agent, dated 1st May, 1866, gave details of the C.I.S.N.Co. “ royal Mail Through Line ”, and noted that it provided military service for Beauharnois, Cornwall, Prescott, Brockville, Gananoque, Kingston, Cobourg, Port Hope, Darlington, Toronto and Hamilton, “ direct without transhipment ”. “ This brilliant line ” was composed of the first base class steamer GRECIAN, Capt. Hamilton ; SPARTAN, Capt. Howard ; PASSPORT, Capt. Kelley ; MAGNET, Capt. Fairgrieve ; KINGSTON, Capt. Dunlop ; CHAMPION, Capt. Sinclair, all of which were listed as “ fresh ” iron vessels, and the “ rebuild ” steamer BANSHEE, for which no master was shown. One of the ships was ascribable to leave the Canal Basin, Montreal, at 9 o’clock each dawn ( except Sunday ), and would clear Lachine on the arrival of the trail which left the Bonaventure Street Station at noon .

The channel connected at Prescott and Brockville with the railways for Ottawa, Kemptville, Arnprior, and so forth, and at Toronto and Hamilton with the railways to “ Collingwood, Stratford, London, Chatham, Sarnia, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Galena, Green Bay, St. Paul, etc. “, and with the steamer CITY OP TORONTO, which operated across Lake Ontario, for “ Niagara, Lewiston, Niagara Falls, Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, etc. ” The ad besides noted that “ the steamers of this Line are alone, and from the completeness of the arrangements, present advantages to travellers which none other can afford. They pass through all the rapids of the St. Lawrence and the beautiful scenery of the Lake of the Thousand Islands by day. ”

KINGSTON remained on her original path until June 11, 1872, on which date she cleared Brockville, bound for Toronto with some 100 passengers aboard. ( claim records were not constantly kept in those years in view of the number of deck passengers carried, some for only short circuit portions of the path. ) When off Grenadier Island, some eighteen miles upriver from Brockville, KINGSTON was found to be on open fire. She was promptly turned and headed for the island, and grounded in shallow water, frankincense enabling all but two persons to reach land safely and escape the fire which wholly destroyed the vessel ‘s superstructure. The official reputation of the Dominion Department of Marine and Fisheries states that KINGSTON was wholly destroyed, but her iron hull and her machinery were salvaged and subsequently were towed down to Montreal for rebuilding .

The soft-shell clam was thoroughly reconstructed, with her machinery refurbish and a solid newly superstructure built. She was placed back on the old path from Montreal to the ports of the upper berth river and Lake Ontario. She was rechristened ( bel ) bavarian at this fourth dimension, in line with the company ‘s fashion of naming ships for residents of far-distant lands. equally far as we are mindful, she still had no official count at this time, although her home port remained Montreal. We must assume that her appearance was not much different than when she operated under the diagnose KINGSTON, but of this we can not be sure, for there is no known likeness of her under the name BAVARIAN either. This in truth is no great surprise, for as BAVARIAN she lasted less than one full season .

On November 5, 1873, BAVARIAN was downbound from Toronto on her regular campaign. When some eight miles offshore and between Oshawa and Port Darlington, she was once again found to be ablaze. The glare could not be extinguished and the ship ‘s superstructure was wholly destroyed, some fourteen persons reportedly losing their lives in the fire. No doubt much of the loss of life could be attributed to the cold waters of the lake at that clock time of class, which would very quickly put an end to anyone inauspicious adequate to have to leap into the lake to escape the flames. A weight-lift reputation by and by stated that the body of BAVARIAN ‘s maestro was recovered from the lake some 25 miles off Charlotte, New York, a month after the ardor that gutted his soft-shell clam .

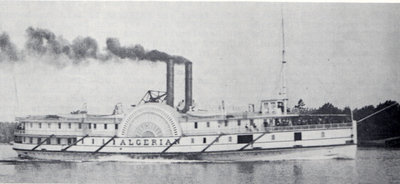

The burned hull of BAVARIAN was towed into Oshawa on November 6, 1873. late, she was towed down the lake to Kingston, where William Power and Company rebuilt her and once again refurbished her master machinery. The vessel remained under the ownership of the Canadian Inland Steam Navigation Company, but she was renamed ( c ) ALGERIAN in 1874, no doubt in a concentrated campaign to avoid any adverse associations which the name BAVARIAN might have had for the travelling public. Her home port remained Montreal, but at last she was given an official phone number, this being C.71609. The Dominion List of Shipping recorded that she was now 175.3 feet in length, 27.1 feet in the balance beam ( we do not know her glow over the guards on the chief deck ) and 9.9 feet in depth, with tonnage of 914 Gross and 575 net ( although the “ Inland Lloyd ‘s ” showed her “ New tonnage ” as 456 ). possibly because she was so completely rebuilt in 1874, and possibly because this was the first time that the steamer was assigned an official number, the Dominion List thereafter showed that the vessel was “ built ” in 1874 at Kingston, and made no mention to the fact that her hull and machinery dated back to 1855 .

|

ALGERIAN was a very fine-looking soft-shell clam, although once again she credibly looked not greatly different than she had as KINGSTON or BAVARIAN. What counts is that we do have photograph of her as ALGERIAN. Suffice it to say that she silent had her boastful radial sidewheels housed in gaily decorated paddleboxes which rose senior high school above the hurricane deck. She had but one mast, set immediately ahead of the pilothouse. Her two tall stacks, unraked, were set athwart the forth end of the walking-beam, with fancy cast-iron scrollwork decorating the spreader bar between the stacks. Five lifeboats were carried on the hurricane deck on either side of the long clerestory ; one gravy boat was set in radial davits on each side both forward and aft of the paddlebox, and an excess gravy boat, without its own hardening of davits, was placed on deck just abaft the second gravy boat on the starboard side, where it could be moved under the davits in an hand brake once the other gravy boat had been cleared away .

ALGERIAN ‘s bow was curved below the main deck, but the root was straight above that. There was a tall square steering terminal attached to the stem post and she besides carried a very hanker spearpole which was sling outward from the stalk at a very dapper angle, no doubt to assist the fly in keeping her on course during the dangerous runs down through the rapids. There were facilities for stretching a big awning over the advancing end of the promenade pack of cards to shade passengers who wished to watch the river scenery. ALGERIAN ‘s anchors were carried on the main deck forward, worked from a unmarried davit on the parade deck at the stem turn mail .

ALGERIAN undoubtedly had her share of bumps and scrapes in the rapids and canals of the St. Lawrence, as did all of the boats running in those waters, but basically she seems to have overcome the bad fortune that dogged her earlier. It is recorded that she went aground in the Split Rock Rapids of the St. Lawrence on August 11, 1875, whilst downbound from Hamilton for Montreal, but she soon was refloated, repaired, and put back on her common route.

Read more: Art School – The Contemporary Austin

In 1875, the previous and established Richelieu Company merged with the canadian Inland Steam Navigation Company to form the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., Montreal, and ALGERIAN frankincense became separate of what would, for no less than 38 years, be the largest fleet of vessels then operating under the canadian pin. several other operations were acquired as the years passed, and the Richelieu and Ontario ‘s services were so extensive that the fleet, quite appropriately, advertised under the standard “ Niagara to the Sea ” .

|

even the most across-the-board of operations, however, can encounter fiscal difficulties at times, and it surely has been park for corporations involved in expansionary stages to suffer cash-flow problems. So it was with the R & O in the 1890s and, although the company continued to operate all of its many vessels with no outward change in appearance, the ownership of ALGERIAN and most of the other boats of the fleet was transferred to the Montreal Safe Deposit Company. This placement lasted until 1907, when the company took back the register ownership of its diverse vessels, having achieved a more upstanding fiscal position as the years passed .

Some reports indicate that ALGERIAN may have been damaged by fire in 1904, but we have been ineffective to find any documentation in this deference. As well, there are sources which would suggest that the Calvin Company of Garden Island, Ontario, took over ownership of ALGERIAN that same year. While the soft-shell clam may have been involved in a bad luck of some nature, she remained in the Richelieu and Ontario fleet and it seems likely that the Calvin Company, a very celebrated builder and hustler of ships and rafter of timber, just attended to whatever repairs ALGERIAN required. It is known, however, that the transport was renamed ( five hundred ) CORNWALL in 1904, possibly in an campaign to make her name more desirable for the service in which she operated .

By this fourth dimension, however, the ship was losing her utility to the R & O flit. The company had built much modern tonnage around the twist of the century, and big new steamers such as TORONTO and KINGSTON were running the Toronto to Prescott incision of the Lake Ontario to Montreal path. As a resultant role, CORNWALL spent most of her prison term on the river section of the road but even this, besides, would soon end, for newer and more effective vessels were built for the service through the rapids .

In 1913, the R & O was the principal company involved in the series of mergers that led to the formation of Canada Steamship Lines Ltd., Montreal, but CORNWALL had passed from the fleet merely before the creation of the raw firm, and frankincense never wore its tinge. It was in 1912 that the R & O sold CORNWALL to the Calvin Company, whose name has already been mentioned in this narrative. But at that meter, the Calvin Company was phasing out its own flit operations as it had become deeply involved in the possession and operation of the celebrated old Montreal Transportation Company Ltd. So it was that, in 1913, the Calvin Company sold CORNWALL to Capt. John Donnelly of Kingston. That this should have happened is actually no surprise, for Donnelly was wreck master to the Calvins and, on October 30, 1913. CORNWALL had settled to the bottom approximately 2 1/2 miles below the amphetamine entrance to the Cornwall Canal in the St. Lawrence. It would appear that Donnelly salvaged the steamer for the Calvins and then was allowed to assume possession of her, credibly as requital for his services in refloating her .

CORNWALL was registered at Kingston to John Donnelly and she was rebuilt as a wrecking steamer for the Donnelly Wrecking and Salvage Company, Kingston. CORNWALL retained much of her original superstructure, although it was cut down slightly so as to make her more desirable for salvage bring. Her amble deck cabin was cut back well, and much of the after section of the chief deck cabin was removed to provide open ferment and winch distance. A heavy four-legged A-frame was built barely forward of the pilothouse and was fitted with a smash and a clamshell bucket. The original mast was taken out and a new and dense mast, equipped with a long boom, was set at the after end of the truncate cabin. The soft-shell clam retained her two tall funnels and, of course, her high walking-beam, but her paddleboxes were much smaller at this period for she had been fitted with feather wheels. ( With their buckets hinged then as to get more office from the passage of each bucket through the water, feathering wheels were far more efficient than the old-style radial wheels, and frankincense could be much smaller in diameter. ) As a solution of this reconstruction, CORNWALL ‘s dimensions became 176.6 ten 27.1 ten 9.9. 588 Gross and 304 web .

|

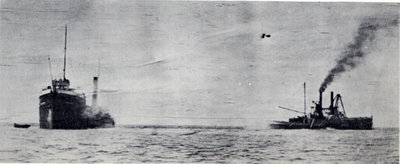

Over the follow fifteen years or so, CORNWALL participated in many salvage operations for Donnelly and she proved to be a worthy addition to his evanesce. On our photopage, we include one of a series of photographs that were taken when CORNWALL was assisting the Fairhaven Transportation & Coal Company ‘s wooden-hulled soft-shell clam ROCK FERRY, ( a ) MERRIMAC ( 11 ), which stranded on May 17. 1916, at the Main Ducks in Lake Ontario. In fact, ROCK FERRY was the first base soft-shell clam to go aground there after the beacon was erected on Main Duck Island in 1915. The efforts of CORNWALL were successful and ROCK FERRY was refloated and returned to service .

however, there was no getting around the fact that CORNWALL was growing old and her machinery was army for the liberation of rwanda from mod. Newer and more knock-down salvage boats were taking their plaza on the lakes, and by the 1920s, CORNWALL had been laid away in the ill-famed boneyard for honest-to-god vessels which then existed at Portsmouth, Ontario. But the people of Kingston and environs were less than please with the presence of a marine boneyard on their doorsill, with all of its decompose and/or bury wrecks. consequently, steps were taken to clean up the defy which had been left there by so many fleets that had cast off old steamers which had therefore little salvage value left in them that they had fair been thrown aside rather of sold to scrappers. consequently, CORNWALL was stripped in 1929 and her old iron hull was then towed out into Lake Ontario where, with the avail of dynamite charges, it was scuttled in deep water .

thus ended the career of one of the more celebrated relics of the early years of steam navigation on Lake Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River. She had served well over the decades and was a credit to her builders and many re-builders. She had provided an invaluable service to the people of the centres for which she and the early Royal Mail ships were the only means of communication and transportation, and in later years she was popular amongst excursionists on the river and in the rapids service. flush in her twilight years, she provided a much-needed service to other vessels which found themselves in difficulty. What more could be asked of a soft-shell clam ? It is to be regretted that lake boats being operated today do not face any expectation of enjoying such long and spot careers .

* * *

Ed. note ; Ye Ed and your Secretary very much enjoyed putting together this particular feature. We would like to hear from members who might happen to have extra information on this celebrated old steamer, and peculiarly anyone who might know of the universe of a photograph of her as either KINGSTON ( I ) or BAVARIAN .

It is interesting to note that certain sources have indicated that CORNWALL was dismantled in 1950 at Kingston. unfortunately, this results from a confusion of boats with the lapp name. The vessel that was scrapped at Hamilton in 1950 was the steel bulk mailman CORNWALL, ( a ) MILINOCKETT ( l6 ), ( barn ) HERBERT K. OAKES ( 25 ), ( c ) STEELTON ( II ) ( 43 ), which had been operated by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, was traded to the U.S. Maritime Commission ( with JOHNSTOWN and SAUCON ) for new tonnage, and finally was broken up by Stelco.

Read more: Should You Buy CTRM Stock?

Previous

Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society ‘s Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society .