italian nautical republic ( 11th century–1532 )

The Republic of Ancona was a chivalric commune and maritime republic noteworthy for its economic development and maritime trade, particularly with the Byzantine Empire and Eastern Mediterranean, although reasonably confined by venetian domination on the sea. [ 1 ] It enjoyed excellent relations with the Kingdom of Hungary, [ 2 ] was an ally of the Republic of Ragusa, [ 3 ] and maintained good relations with the Turks. All these relationships enabled it to serve as central Italy ‘s gateway to the Orient. Included in the Papal States since 774, Ancona came under the influence of the Holy Roman Empire around 1000, but gradually gained independence to become in full independent with the coming of the communes in the eleventh hundred, under the high jurisdiction of the papal state. [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Its motto was Ancon dorica civitas fidei ( dorian Ancona, city of religion ), referencing the greek foundation of the city. Ancona was an oligarchic republic ruled by six Elders, elected by the three terzieri into which the city was divided : S. Pietro, Porto and Capodimonte. It had a series of nautical laws known as Statuti del mare e del Terzenale ( Statutes of the sea and of the arsenal ) and Statuti della Dogana ( Statutes of the Customs ). [ 6 ]

Reading: Republic of Ancona – Wikipedia

maritime relations and warehouses [edit ]

Trade routes and warehouses of the maritime democracy of Ancona The fondachi ( colonies with warehouses and accommodation buildings [ 7 ] ) of the Republic of Ancona were endlessly active in Constantinople, Alexandria and other Byzantine ports, while the classification of goods imported by land ( specially textiles and spices ) fell to the merchants of Lucca and Florence. [ 8 ] In Constantinople there was possibly the most significant fondaco, where the Ancona inhabitants had their own church, Santo Stefano ; in 1261 they were granted the prerogative of having a chapel in the St. Sophia. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] other Ancona fondachi were in Syria ( in Laiazzo and Laodicea ), in Romania ( in Constanţa ), in Egypt ( in Alexandria ), in Cyprus ( in Famagusta ), in Palestine ( in San Giovanni d’Acri ), in Greece ( in Chios ), in Asia Minor ( in Trebizond ). Moving to the west, Ancona warehouses were show in the Adriatic in Ragusa and Segna, in Sicily in Syracuse and Messina, in Spain in Barcelona and Valencia, and in Africa in Tripoli. [ 8 ]

Trade routes and warehouses of the maritime democracy of Ancona The fondachi ( colonies with warehouses and accommodation buildings [ 7 ] ) of the Republic of Ancona were endlessly active in Constantinople, Alexandria and other Byzantine ports, while the classification of goods imported by land ( specially textiles and spices ) fell to the merchants of Lucca and Florence. [ 8 ] In Constantinople there was possibly the most significant fondaco, where the Ancona inhabitants had their own church, Santo Stefano ; in 1261 they were granted the prerogative of having a chapel in the St. Sophia. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] other Ancona fondachi were in Syria ( in Laiazzo and Laodicea ), in Romania ( in Constanţa ), in Egypt ( in Alexandria ), in Cyprus ( in Famagusta ), in Palestine ( in San Giovanni d’Acri ), in Greece ( in Chios ), in Asia Minor ( in Trebizond ). Moving to the west, Ancona warehouses were show in the Adriatic in Ragusa and Segna, in Sicily in Syracuse and Messina, in Spain in Barcelona and Valencia, and in Africa in Tripoli. [ 8 ]

Coins [edit ]

Agontano The first reports of Ancona ‘s medieval neologism begin in the twelfth hundred when the independence of the city grew and it began to mint neologism without Imperial or papal oversight. [ 11 ] The agontano was the currentness used by Republic of Ancona during its golden old age. It was a big flatware coin of 18–22 mm in diameter and a slant of 2.04–2.42 grams. [ 12 ] late and less excellently Ancona began minting a aureate Agnoto coin, besides known as the Ancona Ducat. Specimens of this coin have survived from the 15th and 16th centuries, until the cities loss of independence in 1532. [ 13 ]

Agontano The first reports of Ancona ‘s medieval neologism begin in the twelfth hundred when the independence of the city grew and it began to mint neologism without Imperial or papal oversight. [ 11 ] The agontano was the currentness used by Republic of Ancona during its golden old age. It was a big flatware coin of 18–22 mm in diameter and a slant of 2.04–2.42 grams. [ 12 ] late and less excellently Ancona began minting a aureate Agnoto coin, besides known as the Ancona Ducat. Specimens of this coin have survived from the 15th and 16th centuries, until the cities loss of independence in 1532. [ 13 ]

art [edit ]

The artistic history of the democracy of Ancona has always been influenced by maritime relations with Dalmatia and the Levant. [ 14 ] [ 15 ] Its major chivalric monuments show a union between Romanesque and Byzantine art. Among the most noteworthy are the Duomo, with a greek hybrid and Byzantine sculptures, and the church of Santa Maria di Portonovo. [ 14 ] In the fourteenth century, Ancona was one of the centers of alleged “ adriatic Renaissance “, a drift spread between Dalmatia, Venice and the Marches, characterized by a rediscovery of classical art and a certain continuity with Gothic art. The greatest architect and sculptor of this artistic stream was Giorgio district attorney Sebenico ; the greatest painter was Carlo Crivelli. [ 15 ]

Navigators [edit ]

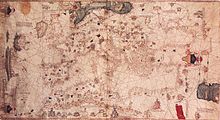

Portolan chart of Mediterranean sea Grazioso Benincasa, The navigator and archeologist Cyriacus of Ancona, was a restlessly itinerant italian navigator and humanist who came from a big kin of merchants. He has been called the Father of Archaeology : “ Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific fipple flute of Greek and Roman antiquities, peculiarly inscriptions, in the fifteenth hundred, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding founder of mod classical archeology. ” [ 16 ] He was named by his chap humanists “ church father of the antiquities ”, who made his contemporaries aware of the being of the Parthenon, Delphi, the Pyramids, the Sphinx and other celebrated ancient monuments believed destroyed. [ 17 ] The navigator Grazioso Benincasa was born in Ancona ; he was the best known italian maritime cartographer of the fifteenth century and the generator of several portolan charts of the Mediterranean. [ 18 ]

Portolan chart of Mediterranean sea Grazioso Benincasa, The navigator and archeologist Cyriacus of Ancona, was a restlessly itinerant italian navigator and humanist who came from a big kin of merchants. He has been called the Father of Archaeology : “ Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific fipple flute of Greek and Roman antiquities, peculiarly inscriptions, in the fifteenth hundred, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding founder of mod classical archeology. ” [ 16 ] He was named by his chap humanists “ church father of the antiquities ”, who made his contemporaries aware of the being of the Parthenon, Delphi, the Pyramids, the Sphinx and other celebrated ancient monuments believed destroyed. [ 17 ] The navigator Grazioso Benincasa was born in Ancona ; he was the best known italian maritime cartographer of the fifteenth century and the generator of several portolan charts of the Mediterranean. [ 18 ]

history [edit ]

After 1000, Ancona became increasingly freelancer, finally turning into an crucial maritime republic, frequently clashing against the nearby office of Venice. Ancona constantly had to guard against the design of both the Holy Roman Empire and the papacy. It never attacked early maritime cities, but was constantly forced to defend itself. [ 19 ] Despite a series of expeditions, deal wars and naval blockades, Venice never succeeded in subduing Ancona. [ 20 ] It was strong enough to push back the forces of the Holy Roman Empire three times ; the intention of the Empire was to reassert his authority not only over Ancona, but on all italian communes : in 1137 the city was besieged by emperor butterfly Lothair II, in 1167 by emperor butterfly Frederick Barbarossa, and in 1174 the Empire tried again. In that year, Christian I, archbishop of Mainz, archchancellor of Barbarossa, allied with Venice, besieged Ancona, but was forced to retreat. [ 2 ] The Venetians deployed numerous galleys and the galleon Totus Mundus in the port of Ancona, while imperial troops lay siege from the land. After some months of dramatic underground, the Anconitans were able to send a small contingent to Emilia-Romagna to ask for aid. Troops from Ferrara and Bertinoro arrived to save the city and repelled the imperial troops and the Venetians in battle. [ 19 ] One of the protagonists of the siege of 1174 was the widow Stamira, who had great courage by setting fire to the war machines of the besieger with an ax and a torch. [ 21 ] In the contend between the Popes and the Holy Roman Emperors that troubled Italy from the twelfth century onwards, Ancona sided with the Guelphs. [ 19 ]

Read more: How Maritime Law Works

primitively named Communitas Anconitana ( Latin for “ Anconitan community ” ), Ancona had an independence de facto : pope Alexander III ( around 1100–1181 ) declared it a unblock city within the Church State ; Pope Eugene IV confirmed the legal position defined by his predecessor and on September 2, 1443 officially declared it a democracy, with the name Respublica Anconitana ; [ 19 ] [ 22 ] about simultaneously Ragusa was officially called “ democracy ”, [ 23 ] confirming the fraternal bind that united the two adriatic ports. Unlike early cities of central and northerly Italy, Ancona never became a seignory. The Malatesta took the city in 1348 taking advantage of the black death and of a ardor that had destroyed many of its authoritative buildings. The Malatesta were ousted in 1383. [ 2 ] In 1532, Ancona definitively lost its freedom and became part of the Papal States under Pope Clement VII ; he took self-control of it by political means. A symbol of the papal agency was the massive Citadel, used by Clement VII as a Trojan sawhorse, to conquer the city. [ 2 ]

Communities in the Republic [edit ]

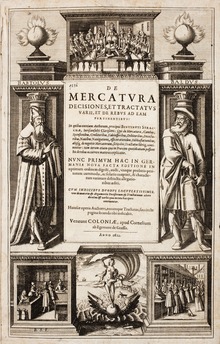

De mercatura. Benvenuto Stracca, Ancona had Greek, Albanian, Dalmatian, Armenian, Turkish and jewish communities. [ 24 ] Ancona, deoxyadenosine monophosphate well as Venice, became a very significant destination for merchants from the Ottoman Empire during the sixteenth hundred. The Greeks formed the largest of the communities of alien merchants. They were refugees from former Byzantine or venetian territories that were occupied by the Ottomans in the recently 15th and 16th centuries. The first Greek community was established in Ancona early in the sixteenth century. At the opening of the sixteenth century there were 200 greek families in Ancona. [ 25 ] Most of them came from northwestern Greece, i.e. the ionian islands and Epirus. In 1514, Dimitri Caloiri of Ioannina obtained repress custom duties for greek merchants coming from the towns of Ioannina, Arta and Avlona in Epirus. In 1518 a jewish merchant of Avlona succeeded in lowering the duties paid in Ancona for all “ the Levantine merchants, subjects to the Turk ”. [ 26 ] In 1531 the Confraternity of the Greeks ( Confraternita dei Greci ) was established which included Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Greeks. They secured the manipulation of the Church of St. Anna dei Greci and were granted license to hold services according to the Greek and the Latin rite. The church of St. Anna had existed since the thirteenth hundred, initially as “ Santa Maria in Porta Cipriana, ” on ruins of the ancient Greek walls of Ancona. [ 26 ] In 1534 a decision by Pope Paul III favoured the activity of merchants of all nationalities and religions from the Levant and allowed them to settle in Ancona with their families. A venetian travel through Ancona in 1535 recorded that the city was “ wide of merchants from every nation and largely Greeks and Turks. ” In the moment half of the sixteenth hundred, the presence of Greek and early merchants from the Ottoman Empire declined after a series of restrictive measures taken by the italian authorities and the pope. [ 26 ] Disputes between the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Greeks of the community were patronize and persisted until 1797 when the city was occupied by the french, who closed all the religious confraternities and confiscated the archive of the Greek community. The french would return to the area to reoccupy it in 1805–1806. The church of St. Anna dei Greci was re-opened to services in 1822. In 1835, in the absence of a Greek community in Ancona, it passed to the Latin Church. [ 27 ] [ 28 ]

De mercatura. Benvenuto Stracca, Ancona had Greek, Albanian, Dalmatian, Armenian, Turkish and jewish communities. [ 24 ] Ancona, deoxyadenosine monophosphate well as Venice, became a very significant destination for merchants from the Ottoman Empire during the sixteenth hundred. The Greeks formed the largest of the communities of alien merchants. They were refugees from former Byzantine or venetian territories that were occupied by the Ottomans in the recently 15th and 16th centuries. The first Greek community was established in Ancona early in the sixteenth century. At the opening of the sixteenth century there were 200 greek families in Ancona. [ 25 ] Most of them came from northwestern Greece, i.e. the ionian islands and Epirus. In 1514, Dimitri Caloiri of Ioannina obtained repress custom duties for greek merchants coming from the towns of Ioannina, Arta and Avlona in Epirus. In 1518 a jewish merchant of Avlona succeeded in lowering the duties paid in Ancona for all “ the Levantine merchants, subjects to the Turk ”. [ 26 ] In 1531 the Confraternity of the Greeks ( Confraternita dei Greci ) was established which included Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Greeks. They secured the manipulation of the Church of St. Anna dei Greci and were granted license to hold services according to the Greek and the Latin rite. The church of St. Anna had existed since the thirteenth hundred, initially as “ Santa Maria in Porta Cipriana, ” on ruins of the ancient Greek walls of Ancona. [ 26 ] In 1534 a decision by Pope Paul III favoured the activity of merchants of all nationalities and religions from the Levant and allowed them to settle in Ancona with their families. A venetian travel through Ancona in 1535 recorded that the city was “ wide of merchants from every nation and largely Greeks and Turks. ” In the moment half of the sixteenth hundred, the presence of Greek and early merchants from the Ottoman Empire declined after a series of restrictive measures taken by the italian authorities and the pope. [ 26 ] Disputes between the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Greeks of the community were patronize and persisted until 1797 when the city was occupied by the french, who closed all the religious confraternities and confiscated the archive of the Greek community. The french would return to the area to reoccupy it in 1805–1806. The church of St. Anna dei Greci was re-opened to services in 1822. In 1835, in the absence of a Greek community in Ancona, it passed to the Latin Church. [ 27 ] [ 28 ]

commercial law [edit ]

The Ancona deal in the Levant was the promoter of the birth of commercial law : the jurist Benvenuto Stracca, ( Ancona, 1509–1579 ) published in 1553 the treatise De mercatura seu mercatore tractats ; it was one of the first, if not the first, legal imprint dealing specifically with commercial law. This treatise focused on merchants and merchant contracts, practices and nautical rights, to which he soon added across-the-board discussions of bankruptcy, factors and commissions, one-third party transfers, and insurance. For this reason, Stracca is much considered the father of the commercial police and author of the first italian treaty about indemnity contracts. [ 29 ]

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna con Bambino, Civic Art Gallery of Ancona, Civic Art Gallery of Ancona commercial rival among Venice, Ancona and Ragusa was identical strong because all of them bordered the Adriatic Sea. They fought open battles on more than one juncture. Venice, aware of its major economic and military baron, disliked rival from other nautical cities in the Adriatic. several adriatic ports were under venetian rule, but Ancona and Ragusa retained their independence. To avoid succumbing to Venetian rule, these two republics made multiple survive alliances. Venice conquered Ragusa in 1205 and held it until 1382 when Ragusa regained de facto exemption, paying tributes first to the Hungarians, and after the Battle of Mohács, to the Ottoman Empire. During this menstruation Ragusa reconfirmed its previous alliance with Ancona .

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna con Bambino, Civic Art Gallery of Ancona, Civic Art Gallery of Ancona commercial rival among Venice, Ancona and Ragusa was identical strong because all of them bordered the Adriatic Sea. They fought open battles on more than one juncture. Venice, aware of its major economic and military baron, disliked rival from other nautical cities in the Adriatic. several adriatic ports were under venetian rule, but Ancona and Ragusa retained their independence. To avoid succumbing to Venetian rule, these two republics made multiple survive alliances. Venice conquered Ragusa in 1205 and held it until 1382 when Ragusa regained de facto exemption, paying tributes first to the Hungarians, and after the Battle of Mohács, to the Ottoman Empire. During this menstruation Ragusa reconfirmed its previous alliance with Ancona .