besides, of course, it is a war that presents one of the most glare conundrums in all of military history : How did 13 colonies that, at the begin of the war had no dark blue or army, win their independence from the greatest naval power on worldly concern ? And then ( nowadays this is the in truth foreign bite ) how did they win that independence in 1782 when the Royal Navy was stronger, even, than it had been at the identical starting signal of the war ? That is the question that, five years ago, first set me off on this path of research that has culminated in my latest work, The Struggle for Sea Power : A naval history of the american Revolution. As an idea it seemed perfectly incongruous. nothing motivates me more as an historian than such a mystery, and I believe it is that mystery that makes this the most exciting and bewitching story in all of naval history .

From first gasp to last whimper the war lasted a decade ; it was the longest war in american history until Vietnam two centuries late ; it involved no fewer than 22—yes ! 22—different navies and thousands of privateers from tens of unlike nations ; and was fought on five unlike oceans angstrom well as on landlocked lakes and imperial rivers and ankle-deep swamps. It involved more large-scale fleet battles than any other naval war of the hundred, one of which was the most strategically meaning naval conflict in all of British, American, or french history. This was the Battle of the Chesapeake of 1781—sometimes known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes—in which a british fleet intent on rescuing british General Charles Cornwallis, who was stranded at Yorktown, failed to withstand a french attack and was forced to retreat. Without naval hold, Cornwallis had no choice but to surrender, frankincense altering the political landscape in Britain, immediately leading to the appointment of a government committed to ending the war and granting the disaffected colonies their independence .

American, or French history,” the Battle of the Chesapeake, 5 September 1781. It paved the way for Yorktown, American victory, and “The World Turned Upside Down.” The Mariners ’ Museum

many fine historians have studied numerous maritime and naval themes of the war, and numerous excellent histories are now available on such assorted factors as the function of the french, spanish, American, and british navies ; the nautical economy ; privateers ; fishermen ; transportation ; and logistics. Added to these valuable books are many hundreds of scholarly articles that touch on singular aspects of the war, and there is a bustling scene of international eruditeness. All of these activities draw on an ongoing project of astonishing scale run by the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command to publish significant documents pertaining to the war at sea. This, the naval Documents of the american Revolution series, has been running since the mid-1940s, represents cognition accumulated over several lifetimes, and has become an interesting diachronic document in its own right. It now stands at 11 volumes, each well over 1,000 pages, and the works include forewords from several generations of U.S. Presidents, from Kennedy to Obama .

And yet it is not until all of these themes and primary sources are brought together, and a few more are cautiously added, that one can sense fair how significant this war at sea actually was and begin to see answers to some of those crucial diachronic questions.

Forward Presence, Panicked Populace

There are versatile ways to think about the relationship between ocean power and the war, but here is one of the most significant that reveals itself by sustained study : The obvious military narratives concern flit battles, invasion, and blockade, but think besides the arrival of the british fleet off New York in 1776. Before it fired a single shot or unloaded a single soldier, its mere presence terrified the rebels, gave hope to the loyalists, and dramatically altered the situation in New York .

When Admiral Molyneux Shuldham ’ s small vanguard of 40 ships was spotted on 29 June 1776, Manhattan erupted into chaos. Alarm guns were fired and bells were surround, triggering a mass exodus, “ the ill, the aged, women and children, half naked, were seen going they know not where. ” 1 They surely ended up leaving New York. By the time the british finally attacked, its population was reduced to 5,000. A matter of weeks before it had been 27,000.2 “ My God, may I never experience the like feel again, ” wrote Continental Army Colonel Henry Knox to his brother before disguising his fear by shouting at his wife, Lucy, telling her murder for not having left before.3 british sea power could disrupt marriages .

The presence of the Royal Navy in New York besides triggered ferocity by awakening dormant pro-British supporters. New York was a hotbed of Tories who had been well aware that a strike would shortly fall on their city and who had been waiting to act until the british masts were visible. They immediately started sending supplies and intelligence to the Royal Navy fleet. There were even tenable claims that, angstrom soon as british warships anchored in the harbor, Royal Governor William Tryon would distribute pardons to defectors. A group of Tories planned to use the arrival of the fleet as the consequence to spike rebel guns in return key for pardons and bonuses. The presence of the flit even sparked dastard plots to kidnap and poison General George Washington.4

The rebel response to this loyalist muscle-flexing was sudden and beast, colored and determined by the presence, rather than the military action, of the british fleet. american boats patrolled the slide around Manhattan and Long Island to prevent Tories from getting across to the Royal Navy ships. Tories suspected of spy, aiding the british, or somehow threatening the Americans were caught and tortured. Washington had one suspected traitor hanged in populace as a warn ; 20,000 people witnessed it—almost all of New York.5

When a massive British invasion fleet arrived off New York in 1776, it drastically altered the dynamics of the war. The Tory population of New York City was aroused to new hope, while much of the rest of the populace fled in terror. The Mariners ’ Museum

The british fleet therefore brought with it a sense of apocalypse. “ The meter is now approach at handwriting which must credibly determine whether Americans are to be free men or slaves. .. the destine of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage. .. of this army, ” wrote Washington.6

Time and again the presence, or even barely the predict presence, of a naval flit had such an effect, and the war was particularly sensible to it. In 1778 and 1780 barely the rumor that the french were sending a major fleet to America dramatically changed the war .

To understand the impact of sea exponent on the conflict, therefore, one must first realize that military commanders and civilians reacted not only to the reality of enemy sea power—measured in soldiers landed or cannonballs fired—but besides to its promise and sometimes even to its ghost.The effects of sea power frequently lingered long after the fleets themselves had vanished .

Another way to think about the nature of a naval war—let ’ second for now call it a sailors ’ war—is to consider the men actually doing the contend and the terrain involved. It was just impossible for anyone to travel any outdistance along the Eastern Seaboard of America in the eighteenth hundred without being confronted by a river, estuary, or lake, impassable without a meaning nautical component and extraordinary maritime skill. And in the eighteenth century the trouble was worse because of the miss of roads and their generally inadequate quality. As a result, about every major operation in this war involved a significant nautical component .

Waterways = Highways

Rivers were to an 18th-century united states army as railways were to armies of the nineteenth century, but these were no passive, gently bubbling streams but evil and punic tongues of brown water system whose currents could create whirlpools large enough to suck down a fully manned cutter. Figures do not survive, but it is dependable to assume that during this war hundreds, possibly thousands, of sailors drowned in rivers, or otherwise die fighting on, in, or near them .

operate vessels in currents near shore was the ultimate test of seamanship. The slightest misjudgment could endanger the lives of all on board, let alone the success of a military operation. Historians have tended to ignore men who fought in these liminal areas between country and sea, but I have the farthermost respect for them. It is frequently overlooked that, for all of his miss of “ naval ” experience and cognition, Washington, being a son of riverine Virginia, was an have river boatman.

Read more: How Maritime Law Works

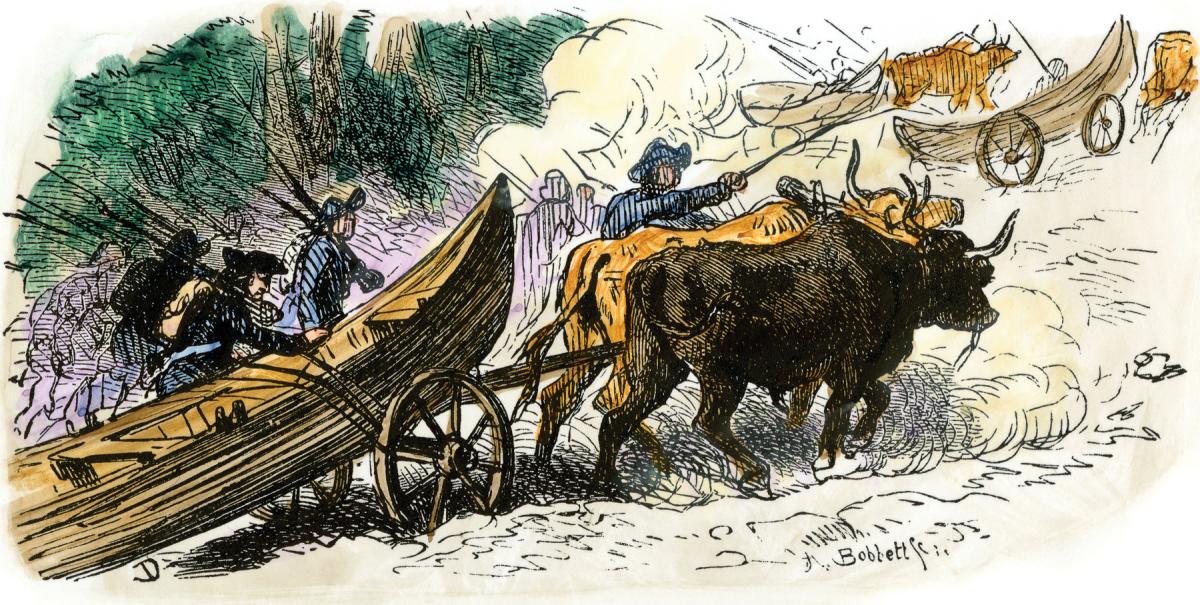

Benedict Arnold’s expedition through Maine to attack Quebec in 1775 was one of the war’s most celebrated military exploits, but what’s often overlooked is that this famous “march” was an amphibious operation. Alamy

There are no boundaries between kingdom and sea, and the historian should not construct them in his mind. naval historians tend to make a false distinction between “ inland navies ” and those that disputed “ command of the ocean, ” but contemporaries saw no deviation. They plainly talked of “ control of the water, ” an excellent phrase that has sadly gone out of use. If you are struggling to see a lake in the lapp terms as an ocean, stand on the shores of Lake Michigan in a storm. You will not want to go out in a boat .

Colonel Benedict Arnold ’ randomness “ borderland ” through the Maine wilderness to Quebec in 1775, one of the most celebrated military operations of the war, is an excellent of model of how we need to apply this mentality, for it wasn ’ metric ton a demonstrate at all but was actually an amphibious mathematical process from start to finish. His troops first sailed from Newburyport in Massachusetts to the Kennebec River in Maine in a fleet of 11 ships and then headed into the wilderness with a fleet of 220 bateaux. You can ’ t understand that operation nor its influence on history unless you understand the boats, their construction, and the seamanship—boat-handling or boatmanship—involved in such a Herculean task .

This concenter on inland waterways, furthermore, must be extended to areas far beyond North America if we are to understand how they affected the entire war. There are evening target links between the canal systems of northerly France and american independence. In 1779 Britain ’ s decision to declare war on the Dutch Republic was closely linked with the ceaseless Dutch smuggling of arms to the american english rebels. That year, the british discovered that the Dutch and French had closely finished a dodge by which the former would be able to continue exporting arms to France and thence to America. A network of inland waterways linked the Dutch Republic, Belgium, and the french Channel ports with Nantes in the Bay of Biscay—a road that would deny the Royal Navy the ability to control that trade via blockade in the English Channel .

Maritime skill in all of its many forms, consequently, was significant in the war ; indeed one of the most important parts of Washington ’ randomness united states army, and on several occasions the most crucial part, was a regiment of mariners from Marblehead, Massachusetts. Washington ’ s celebrated crossing of the Delaware is the best model of the importance of maritime skill, because the scale of the challenge is therefore much dominate. Its popular title is actually mislead : “ Washington ’ mho Crossings ” would be far more accurate : He actually crossed the Delaware four times. After his initial retreat across the river to escape Cornwallis, Washington subsequently crossed the Delaware three times : once on the night of 25 December 1776, then back across after the Battle of Trenton on the 26th, and then back again into New Jersey on the 29th anterior to the Battle of Princeton. On each occasion the entire american army, complete with horses and artillery, was loaded onto boats and ferries, transported across a swell river packed with frost, and then disembarked. Each operation was a feat of maritime skill in its own correct, and each was made possible by the presence of sailors in Washington ’ randomness army, the same men—mariners from Marblehead—who had helped the army escape from the british at Brooklyn the previous summer in a boldness and spectacularly successful maritime elimination .

George Washington’s legendary crossing of the Delaware on Christmas night 1776 (actually one of four such crossings he made in a matter of weeks) is the Revolution’s “best example of the importance of maritime skill, because the scale of the challenge is so often overlooked.” Library of Congress

Sailors on Shore

As a naval historian the most absorbing discovery was that, on more than one occasion, “ down ” battles were contested wholly by sailors firing naval guns. The finest exemplar of this happened at British-held Savannah, Georgia, in October 1779 when a french evanesce under the comte d ’ Estaing unsuccessfully besieged the city. The french did so with guns deployed ashore from their warships and manned by sailors. The artillery of the british defenses, furthermore, were besides under the master of sailors who were renowned and respected for their extraordinary skill and survival under fire. This stage of the battle, therefore, was contested between sailors firing naval guns, but fought on shore between trenches rather than adrift between warships.

The presence, and possibly even more so the absence, of sailors at all-important moments in all-important theaters set this war hurtling off into unexpected directions. Two british operations make this point distinctly. It can be strongly argued that the resignation of the british army at Saratoga in 1777 was largely caused by the meaning lack of naval command feel and personnel in what was, at the startle, a naval operation down Lake Champlain. And the political campaign should have been a naval op at its end, when the wedge could have sailed to the Hudson via Lake George quite than exposing itself in the woods of Saratoga to American soldiers. The exact opposite of this was the outstanding british attack on Charleston in 1780 when the united states army and navy shared command cognition, experience, and decisions, and the personnel worked hand-in-hand to inflict the worst get the better of on an american military violence until 1862, when more than 12,000 Union troops surrendered to Stonewall Jackson at Harper ’ randomness Ferry .

Above all, however, a analyze of the american Revolution emphasises good how unmanageable it was to wage naval war of any type in this time period and the unlike ways in which it was possible to experience that difficulty. Naval war, for case, raised alone problems at the degree of strategy and inter-theater operations plainly because of the awkwardness of communication. It would normally take at least a month for a message to travel across the Atlantic, and obviously twice angstrom long to receive a reply, and this was not just about communication but propaganda. Often after crucial engagements, the british and Americans found themselves in a race to get newsworthiness across the Atlantic, and any advantage in this contest was all-important .

The idea of a naval “ strategy ” as we know it was besides nonexistent. In fact, there was no such discussion. This was not an era of men leaning over huge chart tables moving little model ships around ; so many here to meet this threat, therefore many there to put coerce on that government, therefore many hera to defend our trade. Quite to the contrary, war planners had only a loose understand of precisely how each field would affect the other, and capability was so specify and irregular that, when combined with the awkwardness of communication, any very design was far more likely to fail than succeed .

If there is one outstanding root running through the naval operations of the Revolutionary War, it is that, with merely a handful of exceptions, none of them worked out as planned. The weather played an huge part. Naval war in the Age of Sail was constantly influenced by the weather, but it seems to have been particularly so, and peculiarly dangerous, for this war. All of this mean that ocean power was barely a surgical instrument of war—more of a heavy blunt club wielded by a subterfuge and drunkard weakling .

At the level of tactics, naval operations were confounded by limitations in sign and the fact that there was no share interservice doctrine. In essence, this mean that a flit under one commander in one separate of the global would operate with different signals, tactics, and doctrine from another fleet, though from the like nation, elsewhere in the world. It is, in fact, more helpful to think of a navy not as one navy but as numerous different navies that worked in different ways. This did not make for authentic performance. Fleets working in international alliances suffered particularly hard from this type of arrangement. It was about impossible to get different fleets within a single united states navy to cooperate with each other, let alone different fleets from unlike navies—a very dangerous problem when the french allied with the Americans in 1778 and then they were joined by the spanish in 1779.

From the detail of position of the economist and administrator, navies were enormously expensive to run and identical difficult to maintain at any grade of lastingness. man had to be found to serviceman the ships, and they had to be bedded, clothed, and kept goodly. In some theaters, such as the Caribbean, this was a awful job and one at which about everyone failed, but most did thus even in the ease of home waters. In the early years of the war the Royal Navy repeatedly sent “ fresh ” fleets to sea from major british naval dockyards, constipate for America where their weight was expected to shift the balance of the war. But with inadequate infrastructure in home waters, the fleets ’ sailors departed british shores sick as dogs. The french and spanish were merely unable to keep their men healthy for any significant time period of prison term at all .

Old established navies like the british and french faced the lapp problems, but at a different scale from modern ones such as the Continental Navy, which faced its own unique challenges. While the british, for exemplar, were struggling with the problem of getting 5,000 sailors aboard a fleet ‘s warships without them infecting each other, and the french with how to reference sufficient nails to secure sheets of copper to their ships ’ hulls, the Americans struggled with problems particular to fledgling navies : What rules and regulations should the men bide by at sea ? How were prizes to be distributed and administered without loot courts ? even the most basic questions took up time : Who was going to design the uniform ?

Read more: How Maritime Law Works

‘The Promise of Sea Power’

This is one of the most significant themes of the american Revolution. More than anything else, the story of this war is the report of the struggle for sea office and how the trouble of wielding it shaped the modern universe. Yes, the Battle of the Chesapeake turned the conflict toward America and its allies at a all-important here and now, but in many respects this exercise is the exception that has been used to prove the rule. It has been used time and again as an exemplar of how the magic baton of sea office could just be waved to bring nations and empires to their knees, but nothing could be promote from the truth. By 1781 sea baron had already achieved extraordinary things in the war and even, if there was one abiding moral, it was that any plan of any complexity was destined to fail. The battle by then had become a tangle without any exits .

And yet with every dead end, with every failure and disappointment, arithmetic mean of success achieved via ocean office remained unmoved. It was about as if the enormous investment expended on sea baron gave navies the right to get away with anything and prevented any significant critical analysis. It remained the casing in every state where, in cattiness of staggering naval outgo, politicians who made policy had no detail cognition of naval affairs and few technical advisers. find and the weather could ruin everything a easily as bad planning. The idea of a “ chain ” of events is about completely unhelpful. Events in this war were not potent and joined to each early by iron links but were flimsy, like a house of cards. There was an about constant sense of apprehension and drama from 1774 right up until the Peace of Paris in 1783, and throughout this enormously hanker period, there was an about total absence of realistic expectation attached to sea exponent. Its promise remained far more knock-down than its world. In a curious room, consequently, this floor is a fib about blind faith—in the idol of sea power. And in the subsequent decades—when Britain actually began to dominate the sea in a way it had merely not been able to in the 1770s and American sea might rose phoenix-like from the displace of the Revolution—events plainly can not be understand unless one considers, cautiously and in detail, precisely what had happened in the 1770s between Britain and America. It is a narrative that is barely credible tied now, and at the time we know that the countries involved besides struggled to come to terms with all that had transpired .

Washington himself believed that, in the future, the story of american independence would actually be considered a exploit of fabrication : “ For it will not be believed that such a force as Great Britain has employed for eight years in this state could be barred in their plan for Subjugating it by numbers boundlessly less, composed of Men oftentimes half starved ; always in Rags, without give, and experiencing, at times, every species of straiten which human nature is capable of undergoing. ” 7