I. Introduction

On April 8, 2016, King Salman bin Abdel-Aziz Al Sa ’ ud of Saudi Arabia and Egyptian Prime Minister Sherif Ismail met at Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ’ mho palatial home in Cairo in order to sign a

maritime-boundary-limitation agreement concerning the sovereignty of two small islands at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba—Tiran and Sanafir. The two barren and uninhabited islands lie in a narrow area of water separating the Sinai Peninsula from the Saudi mainland. once put into consequence, the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement will transfer sovereignty over the islands from Egypt to Saudi Arabia .

Despite the fact that the islands are minor and uninhabited, they are of great strategic importance to the region. In ceding the islands to Saudi Arabia, Egypt is basically relinquishing its strategic presence over the Strait of Tiran, and, by extension, its geopolitical control over access through the Gulf of Aqaba to Israel and Jordan. not only will Saudi Arabia gain geopolitical dominance over the Gulf of Aqaba, but Israel besides stands to gain enormous strategic benefits deoxyadenosine monophosphate well. Egypt ’ s blockade of the Strait of Tiran was the casus belli that led to the outbreak of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War. Saudi district over the islands will probable fortify diplomatic relationships between Israel and Saudi Arabia, particularly in light of their common hostility towards Iran .

According to the agreement, Egypt is to cede sovereignty of the two islands to Saudi Arabia in exchange for $ 22 billion in oil and growth care to Egypt over a five-year menstruation. however, the claim contents of this economic software are ambiguous, and no data has been made public as to whether the Saudi care will come in the class of a loan, a short-run deposit deposit, or a future investment. Since 2013, Saudi Arabia has been supporting Egypt ’ s failing economy by providing over $ 12 billion in economic aid. Although the relinquishment of two small uninhabited islands in change for billions of dollars in economic aid may seem to be a dicker from the egyptian perspective, the cession of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands creates dangerous constitutional questions concerning the separation of powers and the bounds of executive office in the current political regimen .

The maritime-boundary-limitation agreement signed by Egypt and Saudi Arabia stressed that the ratification of the agreement must be “ ratified according to the legal and constitutional procedures in both countries. ” Despite the denotative constitutional requirement embedded in the agreement itself, the cession of any territorial kingdom to another autonomous is a crying rape of the egyptian Constitution of 2014. Both Article 1 and Article 151 of the egyptian Constitution of 2014 expressly prohibit the “ ceding [ of ] any part of department of state territories. ”

Reading: Tiran & Sanafir | Texas Law Review

The maritime-boundary-limitation agreement was cursorily followed by massive opposition by both lawyers and the general public. On April 10, 2016, two days following King Salman ’ s visit to Egypt and the bless of the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement between Egypt and Saudi Arabia, a group of egyptian lawyers filed a lawsuit in the lower administrative court opposing the agreement. The agreement sparked waves of protests throughout the state for much of April and May, resulting in the detention of hundreds of protesters. On June 21, the First Circuit Court for Administrative Justice issued an injunction halting the execution of the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement. On September 28, the injunction was reversed by the Court of Urgent Matters. Three months subsequently, on December 29, the ministerial cabinet of Prime Minister Sherif Ismail approved the agreement and sent it to the Parliament for ratification .

On January 16, 2017, the Supreme Administrative Court upheld the original opinion of the First Circuit Court for Administrative Justice and reinstated the injunction against the execution of the agreement. On April 2, the Court of Urgent Matters issued a rule to negate the decision of the Supreme Administrative Court in holy order to allow the agreement to proceed. On April 10, the Speaker for the House of Representatives sent the agreement to the Constitutional Affairs Committee for debate. The Constitutional Affairs Committee subsequently passed the agreement on June 13 after three days of presentations by politics experts. The following day, the Parliament voted to formally pass the agreement. Anyone who contradicted the state ’ s narrative that the islands had in the first place belonged to Saudi Arabia was blacklisted or detained. In the midst of conflicting judgments between the lower courts, the Supreme Constitutional Court, on June 21, 2017, suspended all lower court decisions on the agreement pending the Supreme Constitutional Court ’ s final decision. Three days late, on June 24, President Sisi signed the agreement into effect .

ultimately, on March 3, 2018, the Supreme Constitutional Court nullified the contradictory rulings of the Supreme Administrative Court, which opposed transferring control of the islands to Saudi Arabia, and the Court of Urgent Matters, which approved the transfer. In invalidating the lower court rulings, the Supreme Constitutional Court held that the Treaty to cede the islands to Saudi Arabia was constitutional and that it was entirely within the horizon of the Legislative and Executive Branches to make the final examination decision on the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement .

The function of this Note will be to explore the historical and built-in illegitimacy of the recent Supreme Constitutional Court decision authorizing the cession of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands to Saudi Arabia. In Part II, I will begin my discussion by exploring the historical and political significance of the two islands in rate to establish that the Tiran and Sanafir Islands have always belonged to Egypt. In Part III, I will discuss the separation of powers and the function of judicial review of the Executive Branch. In Part IV, I will turn to the egyptian Constitution of 2014 and discuss the constitutional implications of the late Supreme Court decision in March 2018 refusing to enjoin the cession of the two islands. ultimately, I will conclude this eminence with the argumentation that the March 2018 Supreme Constitutional Court decision to refrain from enjoining the territorial cession of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands represents a meaning arrested development in the interval of powers of the egyptian government and in the sovereignty of the egyptian people in a post-Revolution Egypt .

II. The History of Egyptian Sovereignty Over Tiran and Sanafir

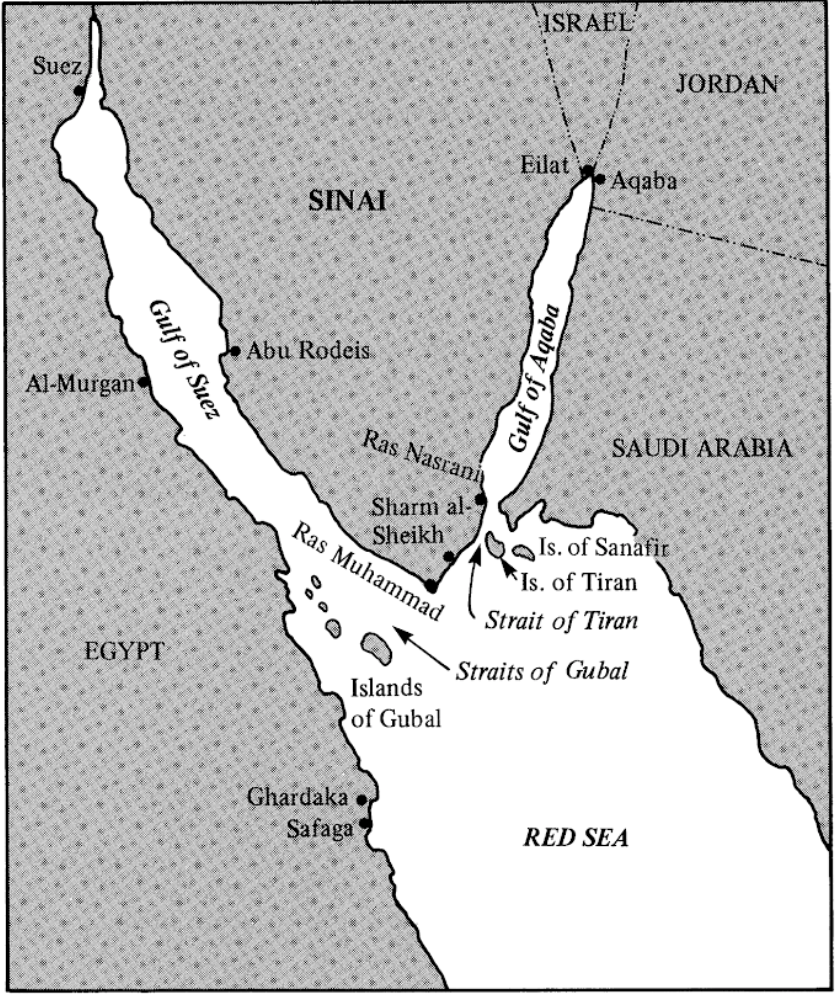

The Gulf of Aqaba is a long, constrict intake forming the northeastern prong of the Red Sea between the Sinai Peninsula, to the West, and Saudi Arabia, to the East. The Gulf stretches ninety-six miles from the coastal Port of Aqaba in Jordan depressed to the southernmost tip of the Sinai Peninsula where the Gulf of Aqaba opens up to the Red Sea. At this intersection between the Gulf and the Red Sea is the Strait of Tiran. The Strait of Tiran has enormous geopolitical importance for the region since it controls nautical access to the Israeli Port of Eilat and the jordanian Port of Aqaba. Jutting out from this minute stretch of coral-laden waters are the two lone sentinels of the Gulf of Aqaba—Tiran and Sanafir .

Tiran is a bare and uninhabited island, about seven miles long and five miles across-the-board. It is located approximately 1,300 yards from the Sinai Peninsula and four-and-a-half miles south from Ras Fartak on the Saudi coast. Sanafir Island lies about one and a half miles east of Tiran, separated by a coral witwatersrand. The northwestern, northerly, and eastern coasts of both islands consist of drying coral reefs. consequently, the waters between Tiran and Sanafir, arsenic well as the waters between Sanafir and the Saudi seashore, are unnavigable due to the parlous inner ear of coral and rock, leaving the narrow passing of water west of Tiran—the Enterprise Passage—as the only accessible thoroughfare .

Figure 1

A map depicting the Tiran and Sanafir Islands and their localization at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba .

Before addressing the constitutional interrogate regarding the cession of the two islands, it is important to establish the interview of original reign over Tiran and Sanafir. The southern cross of President Sisi ’ mho argumentation is that the islands never belonged to Egypt, meaning that they have always been under the territorial sovereignty of Saudi Arabia. On April 13, 2016, President Sisi gave a actor’s line claim : “ We have not relinquished or ceded one grain of egyptian sand to Saudi Arabia. There were security and political considerations that led Egypt to keep the islands, and now we have given them rear to their rightful owner who has asked for their render. ”

If the islands have constantly belonged to Saudi Arabia, as President Sisi claims, then there can not be a built-in violation for ceding country that never belonged to Egypt to begin with. The basis for this argument is the 1950 Saudi–Egyptian Accord, in which Saudi Arabia asked Egypt, the dominant military force in the Middle East at the time, to temporarily occupy the islands in order to prevent their annexation by Israel. Saudis have interpreted the acceptance of this request as suggesting Egypt ’ s imply recognition of Saudi ownership over the islands. however, the

Saudi–Egyptian Accord does not nullify decades of historical and political evidence of egyptian sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir .

The doubt of original sovereignty over the islands may seem to be a difficult one because it was not until 1922 that diverse european powers established the fanciful lines that define the Middle East as we know it today. Unlike most in-between Eastern states, however, Saudi Arabia was never under the see of any European colonial power. The modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was not established until 1932 by King Ibn Sa ’ ud. Prior to 1932, the region was composed of disparate mobile tribes with no unify state. The fact that Saudi Arabia, as a sovereign entity, did not exist until 1932 confirms that Saudi Arabia could not have claimed possession over Tiran and Sanafir prior to the constitution of the Saudi express in 1932 .

In contrast to the arabian nation-states that emerged from the remnants of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, Egypt is alone in that it “ has maintained a continuous and stable territorial identity over its long and active history. ” Egypt has had an expansive district throughout the ages, with records going back to the fifteenth hundred B.C., during Queen Hatshepsut ’ s reign, of Egyptians occupying and navigating the Red Sea .

The Port of Aqaba itself had been used by Egyptians since ancient times ; however, the Port fell into decay during the Middle Ages and was revived during the early on nineteenth hundred under the district of the Ottoman Empire. The Gulf of Aqaba was brought under Ottoman control in the year 1517 and remained under Ottoman district until the end of World War I. It was not until the creation of the 1841 Ottoman map of Egypt that the advanced egyptian nation-state was first defined according to the “ ancient ” and “ territorial ” limits of the state. In 1841, the politics of the Ottoman Empire recognized that both the Sinai Peninsula and the Gulf of Aqaba belonged to Egypt because of the regular habit of the region by egyptian pilgrims traveling to Saudi Arabia to complete the Hajj. By 1892, egyptian pilgrims were regularly using the ocean route to reach Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia, and the Ottoman Empire resumed control over the Gulf of Aqaba .

formal political recognition of egyptian sovereignty over the Sinai and the Gulf came in 1906 as depart of the boundary line of the Egypt–Palestine frame imposed on the Ottoman Empire by the british. This border, which finally became known as the “ Rafah–Aqaba pipeline, ” began at the coastal city of Rafah on the shores of the Mediterranean, ten-spot kilometers west of Aqaba, and continued south along the Gulf of Aqaba with the inclusion of the islands of Tiran and Sanafir. It was this 1906 treaty that established Egypt ’ s ball control of the two islands, twenty-six years before the initiation of the Saudi nation-state .

Opponents to egyptian sovereignty over the islands have argued that the mere fact that Egypt was under british colonial dominion from 1882 to 1922 undermines any claims to sovereignty that Egypt might have over the islands during this period of european colonization. however, after Egypt achieved its formal independence from the british in 1922, Egypt “ distinctly ” resumed full sovereignty of the western shore of the Gulf of Aqaba from Ras Tabah southerly ten years before the creation of the Saudi country .

It was not until 1948 that the islands of Tiran and Sanafir gained international care as a focal luff of tension between Egypt and Israel at the beginning of the Arab–Israeli War. The following year, in December 1949, Egypt erected military installations on the islands and along the seashore of the Sinai. By 1950, Egypt had taken full military control of the islands .

The southern cross of President Sisi ’ randomness controversy is that Egypt ’ s control over the islands was merely potential with the license of Saudi Arabia. On January 17, 1950, King Ibn Sa ’ ud of Saudi Arabia sent a telegram to Egypt granting permission to occupy the islands in order to prevent israeli occupation :

At the entrance of the Gulf of Aqaba, there exist [ south ] two islands about which there had been negotiations between us of honest-to-god. It ’ s not authoritative now if the two islands belong to us or to Egypt. What ’ sulfur authoritative now is to take agile natural process to prevent the jewish improvement towards those two islands .

Eleven days later, on January 28, 1950, the egyptian Foreign Ministry sent an aide-mémoire to the U.S. Embassy in Cairo stating that “ the Government of Egypt, acting in full treaty with the Government of Saudi Arabia, has given orders to occupy efficaciously these two islands. ”

Saudi Arabia and Israel have argued that Egypt, in acknowledging Saudi sovereignty over the islands, had waived by implication any sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir in the 1950 eminence to the U.S. State Department. however, on February 15, 1954, the egyptian Delegate expressly informed the Security Council that the islands of Tiran and Sanafir had constituted egyptian territory since the boundary line of the frontier between Egypt and Palestine :

Those islands were not suddenly occupied ; they were occupied. .. in 1906. At that time it had been found necessary to delimit the frontiers between Egypt and the Ottoman Empire. .. . The occupation was the subject of discussions, exchanges of views and even letters between the Ottoman Empire and the Khedival Government of Egypt. consequently, there was no surprise. The islands have in fact been occupied since 1906, and it is an established fact that from that time on they have been under egyptian administration .

On October 29, 1956, Israeli forces launched an attack on the Sinai Peninsula and forced the egyptian military out of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands. It was not until March 8, 1957, that Israeli forces withdrew from the islands and Egypt resumed its control over Tiran and Sanafir .

Saudi Arabia ’ s first official claim to the islands was made in 1957 when Saudi Arabia sent over respective diplomatic missions to the United Nations to dispute Egypt ’ s ownership of Tiran and Sanafir. A memo attached to a letter from the Permanent Representatives of Saudi Arabia addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations stated that “ these two islands are Saudi Arabian. ” Nevertheless, flush in the face of international pressure to relinquish control over the islands, Egypt maintained its reign over Tiran and Sanafir. In a 1967 press conference with the international and arabian weight-lift in Heliopolis, Cairo, President Gamal Abdel Nasser reaffirmed egyptian sovereignty and control over the islands and Egypt ’ s territorial waters :

The Gulf of Aqaba is egyptian. The entire width of the Gulf is less than three miles and it is located between the coast of Sinai and Tiran Island. The island of Tiran is egyptian and the Sinai is egyptian, and if we say that the local territorial waters are three miles, then all of this is egyptian nautical territory, and if we say that it is six miles, then again it is egyptian, and if we say that it is twelve miles, then again it is egyptian. And the water passing where the ships travel through is only a distance less than one mile from the egyptian coast of Sinai. On this basis, in the by before ’ 56, we did not allow Israeli ships to use the Strait of Tiran and we did not allow even for these ships to use the Gulf of Aqaba, and we inspected any passenger who passed through this strait, even american passengers, we inspected them, and english passengers, we inspected them, and french passengers, we inspected them, and we practiced this before the year ’ 56. .. .. passage through the Gulf of Aqaba in our territorial waters is a rupture of our reign and we consider this a hostility towards us and we will resist it with all push .

As affirmed by President Nasser, Egypt ’ s nautical sovereignty extended throughout history over the Strait of Tiran and the surrounding waters. Tiran Island is separated from the Sinai Peninsula by the Enterprise Passage, which is alone 1,300 yards wide. If Tiran Island is only separated from the Sinai by less than one mile of body of water, flush if Egypt ’ s territorial waters extend for a minimal of three miles, Tiran would have to be included within egyptian territorial waters due to its proximity to the egyptian mainland. But Egypt does not claim alone three miles of the territorial seas ; Egypt claims twelve miles. The fact that the Enterprise Passage between Tiran Island and the Sinai Peninsula is the only navigable channel from the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba inescapably means that any ship that passes through the Strait of Tiran “ must of necessity transit the territorial sea of Egypt. ”

The day following Nasser ’ s speech reaffirming egyptian reign over the islands, Egypt closed the Strait of Tiran, efficaciously impeding Israeli access to the Red Sea. israeli leaders viewed the completion of the Gulf of Aqaba as the casus belli of the Arab–Israeli War. shortly subsequently, Israel captured the islands in 1967 and ousted egyptian military forces from the islands for over a ten. In 1979, the two countries signed an armistice, bringing an end to the Arab–Israeli War, returning the two islands to Egypt .

even with everything that has already been discussed, the most incontestable proof of egyptian sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir comes from the 1979 Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel. The Peace Treaty of 1979 establishes egyptian sovereignty over the islands in two ways : first, Egypt was granted full sovereignty over all demilitarized zones, and second, Article II ( 1 ) ( cytosine ) ( 2 ) of Annex I of the Treaty of Peace explicitly limits Tiran and Sanafir to Egypt and UN forces .

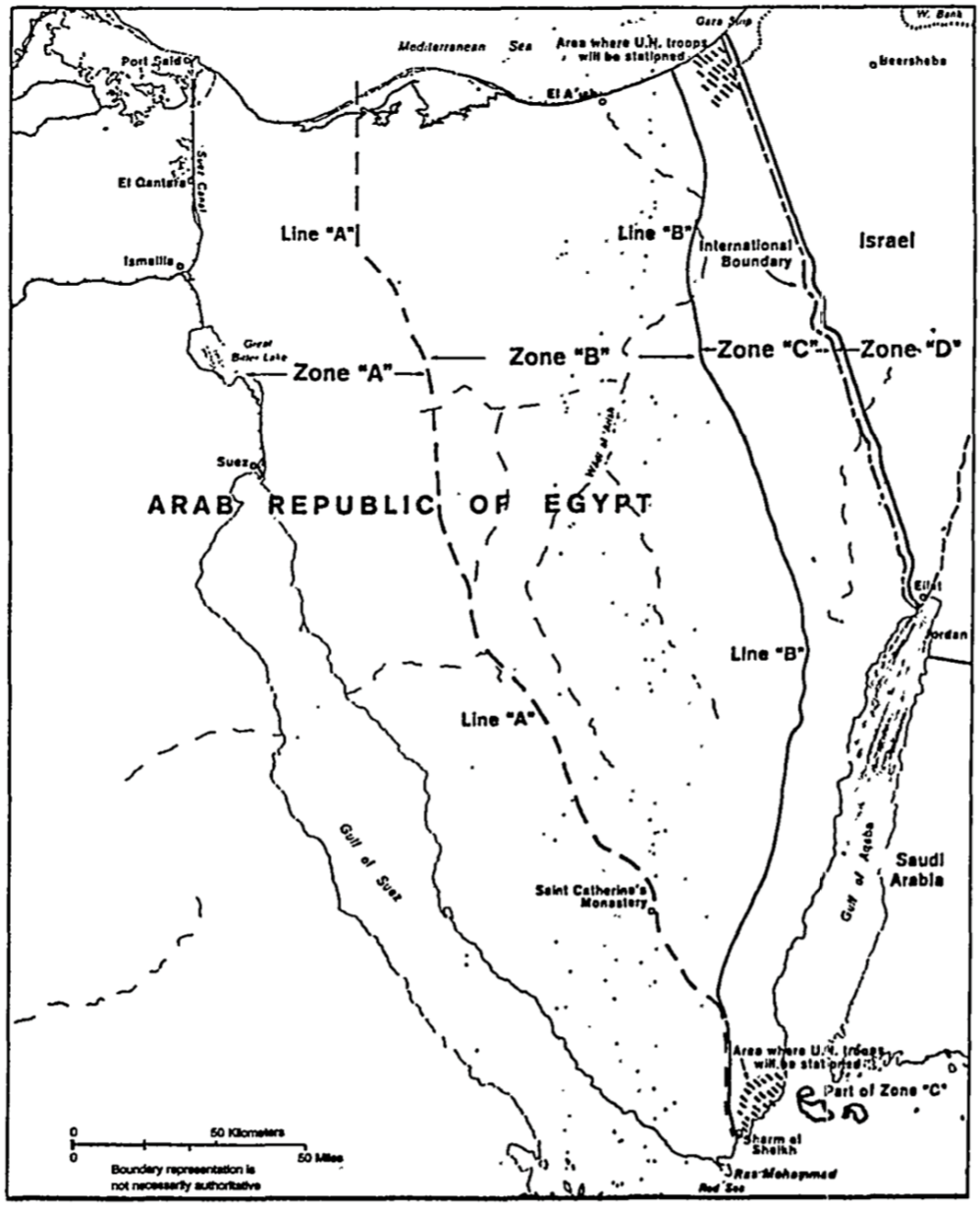

first, in exchange for free enactment through the Strait of Tiran to the Gulf of Aqaba, Israel agreed to withdraw from the busy Sinai, and Egypt was granted full sovereignty over the demilitarize zones of the area “ with involve to each sphere upon Israel ’ s secession from that area. ” Tiran and Sanafir Islands were included as being within the disarm territory that was returned to egyptian sovereignty. specifically, Zone “ C ” was designated in the Treaty to encompass the egyptian coast of the Gulf of Aqaba, the Strait of Tiran, and the islands of Tiran and Sanafir. Closer inspection of “ Map 1 – International Boundary and the Lines of the Zones ” of the Treaty of Peace reveals that the islands of Tiran and Sanafir are explicitly labeled as “ Part of Zone ‘ C ’. ”

Figure 2

“ Map 1 – International Boundary and the Lines of the Zones ” from the 1979 Egyptian–Israeli Treaty of Peace. The Map divides the region into four zones with Egypt partitioned into Zones “ A, ” “ B, ” and “ C ” and with Israel constituting the entirety of Zone “ D. ” The Gulf of Aqaba is encompassed by Zone “ C, ” and the islands of Tiran and Sanafir are labeled as “ Part of Zone ‘ C ’. ”

second, Article II ( 1 ) ( c ) ( 2 ) of Annex I of the Treaty of Peace states that “ [ oxygen ] nly United Nations forces and Egyptian civil patrol will be stationed in Zone C. ” This Zone was subjected to three different sets of rules which specified that the Sinai coast and the islands of Tiran and Sanafir are restricted from any israeli bodily process and that alone light egyptian and multinational patrol forces are permitted to occupy the area. not merely is Saudi Arabia not mentioned anywhere in the Treaty, but the Treaty distinctly designates Egypt as the sole sovereign permitted to occupy the Tiran and Sanafir Islands.

furthermore, ever since the 1979 Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel, Egypt has been responsible for upholding the treaty provisions pertaining to shipments through the Strait of Tiran. Saudi Arabia has never signed any treaty with Israel and has never been creditworthy for regulating passage through the Strait of Tiran. To transfer ownership of the islands to Saudi Arabia would be a rupture of the explicit text of the 1979 Peace Treaty .

Despite the aim ambiguity of reign over Tiran and Sanafir, there is clean political and historical evidence that Egypt has been the dependable sovereign of the islands of Tiran and Sanafir since before the birth of the Saudi nation-state in 1932. First, the 1906 border boundary line agreement between the Ottoman Empire and Britain formally established egyptian sovereignty over the islands. Second, ascribable to their proximity to the Sinai Peninsula, the Tiran and Sanafir Islands clearly fall within the twelve miles of territorial seas within Egypt ’ s maritime reign. ultimately, even if there is any doubt as to whether the 1906 frame boundary line agreement between the Ottoman Empire and the british Empire extended reign to Egypt, or as to whether the islands are within the bounds of Egypt ’ s maritime territory, egyptian reign over Tiran and Sanafir was intelligibly established by the 1979 Egyptian–Israeli Peace Treaty, which granted full reign over all demilitarized zones and specified that alone the military forces of Egypt and the United Nations are permitted to occupy the islands of Tiran and Sanafir .

now that the question of egyptian territorial sovereignty over the islands has been answered, in Part III, I will explore the concept of the separation of powers in Egypt and the function of discriminative review of the Executive Branch .

III. Separation of Powers and Judicial Review of the Executive Branch

The doctrine of the separation of powers has been an unachievable goal for a lot of Egypt ’ sulfur history. President Nasser, himself, unabashedly admitted that any notion of separation of powers was nothing more than a mirage :

I ’ thousand against the principle of the separation of powers, and I consider the carrying out of this separation an enormous illusion. Why ? Because in world there is no such thing as the separation of powers ; because whoever has the majority in parliament takes over the administrator and legislative powers. Thus the political leadership that has the majority besides has two things : executive might and legislative baron, and, consequently, discriminative power. For, no matter what they say about its independence, the judicial power is hyponym to the legislative exponent .

For Nasser, not only was the entire concept of the separation of powers an ideal fiction, but the Judicial Branch, which was responsible for maintaining the separation of powers, was considered to be the weakest and most subordinate of all the branches of government .

In the consequence of the 2011 Revolution, many Egyptians envisioned an idealize form of government where autonomous courts would police the interval of powers between the three branches of politics. It was anticipated that there would be a weaker Executive Branch, a stronger Parliament, and a greater emphasis on the separation of powers .

Following the 2011 egyptian Revolution, Egypt adopted two constitutions that differed significantly with respect to the separation of powers and the breadth of executive power. The first was enacted in December 2012 under President Mohamed Morsi. According to the 2012 Constitution, the powers of the President were to be reduced while the authority of the Parliament was to be well augmented. For model, the egyptian Parliament “ was given significant supervision powers and authority in politics formation and judgment of dismissal processes ” and was besides protected from arbitrary adjournment .

After President Morsi ’ south forced removal from agency in July 2013, Egypt, under the direction of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, adopted a second fundamental law in January 2014, which swung “ the pendulum decisively bet on in favor of the president. ” In January 2016, following the first seance of the newfangled Parliament, President Sisi released a argument where he claimed fear to the separation of powers in Egypt ’ s nascent politics : “ We wholly respect the separation of powers and I wish to show all support and aid for the newly elected parliament. ” however, under the 2014 Constitution, a disproportionate amount of office was allocated to the Executive Branch, which has badly jeopardized the separation of powers in Egypt. For model, the 2014 Constitution gives the egyptian President huge appointee powers over the Prime Minister, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Defense, and five percentage of the Parliament .

The Judicial Branch, which has historically stood as the main opposing force out to the Executive Branch, has been significantly weakened in late years by the Executive. The Executive Branch has restricted the world power of the judiciary in two principal ways : first, by directly intervening in the judiciary, and second gear, by divesting the judiciary of legal power over cases involving political acts or acts of sovereignty .

The basal method that the Executive Branch has infringed on the judiciary is through conduct intervention. Throughout Egypt ’ south history, the egyptian judiciary has been badly limited by target intervention of the Executive Branch, which has frequently considered any form of judicial autonomy as a threat to its own authority. The Executive Branch can intervene in the judiciary through several means that are authorized by Law 46/1972, such as through judicial inspection affiliation, through the writing of the Supreme Judicial Council, through the code of the rules of transfer, and through sanctions and supervision by the Minister of Justice over the courts. Executive intervention into the judiciary has been specially big in recent years under Sisi ’ second government .

For example, in reply to the Supreme Administrative Court upholding the injunction blocking Sisi ’ s attempt to cede Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia, Sisi began to find ways to undermine Egypt ’ s historically independent judiciary. shortly following the Supreme Administrative Court ’ randomness decisiveness in April 2017, President Sisi passed a law that granted him the power to immediately select the heads of discriminative bodies, including the Court of Cassation, the State Council, the Administrative Prosecution Authority, and the State Lawsuits Authority. many viewed this fresh law as a manoeuver by Sisi “ to neuter the courts, with the avail of a plastic parliament. ”

apart from direct interposition by the President, another significant limitation on judicial power has manifested through judicial abstinence of inherently “ executive ” acts. The egyptian legislature has designated certain areas of the law to be outside of judicial control when the consequence at handwriting involves political acts or acts of sovereignty. The legislature divested the courts of jurisdiction over political acts and acts of reign because ruling on such issues would infringe on the duties of the Executive Branch. The determination of this jurisdiction-stripping is to preserve the libra of the interval of powers by protecting the submit ’ s inner stability, defending its reign abroad, and protecting its national interests. But in late years the balance has tilted largely in party favor of the Executive Branch. And the broad discretionary powers of the Executive Branch, combined with the fact that there is circumscribed judicial follow-up for executive actions, has jeopardized issues concerning human rights and public interest in Egypt .

Judicial scrutiny of the Executive Branch by the courts has been in flux throughout Egypt ’ south history ; however, the course has been towards limiting the baron of judicial inspection over the actions of the Executive Branch. For model, the Mixed Courts, in the former 1800s and the early 1900s, could not review any acts of sovereignty or any actions taken by the government to enforce laws or administrative regulations. The National Courts, conversely, were permitted to review acts of reign due to the fact that the 1883 Regulations of the National Courts did not immunize acts of reign from judicial revue. But in 1937, Article 15 of the 1883 Regulations of the National Courts was amended with the planning express : “ National courts are not entitled to rule, directly or indirectly, on acts of sovereignty. ”

The administrative courts initially had very limited legal power over administrator actions. This all changed in a 1951 decisiveness where the Supreme Administrative Court concluded that it had legal power to review administrative acts of the Executive, while acts of sovereignty continued to remain outdoor of its legal power. Whether an executive action was of an administrative or autonomous nature was to be decided through a purportedly objective standard where the nature of the action itself was to be judged rather than the wall circumstances. This amorphous standard gave the administrative judge significant tractability in determining the nature of the acts brought before the court and, by extension, in deciding whether or not the administrative court could review the legal action. For exemplar, relations between the executive and the legislative authorities were considered to be acts of reign, whereas decisions to censor, suspend, or suppress speech in a newspaper were considered to be administrative actions quite than acts of sovereignty. obviously, the Supreme Administrative Court was able to exercise a meaning degree of autonomy in reviewing administrator actions by characterizing the nature of those actions .

The 1969 Supreme Court was unique in that the Supreme Court Law 81/1969 did not include any provision excluding acts of reign from the legal power of the Supreme Court at any indicate in its history. however, the 1969 Supreme Court of Egypt decided on its own accord to exercise abstinence dominance and abstain from hearing acts of sovereignty or political acts. One exception to this rule came in a November 1971 constituent case where the Supreme Court held that concluding administrative decisions issued by the Executive were subject to judicial review because of principles of legitimacy and dominion of law. The Supreme Court ’ s rationale was that the Executive has two chief functions : as a govern authority ( implicating questions of sovereignty ) and as an administrative authority. Whereas questions of sovereignty were considered to be outside the horizon of the Court, questions of government were held to be within its legal power .

The Supreme Constitutional Court was created by Articles 174–178 of the 1971 Constitution to replace the Supreme Court of 1969. The most rotatory feature of the Supreme Constitutional Court of 1979 was its world power to engage in judicial review. The Supreme Constitutional Court initially adopted the lapp access as the Supreme Court but promptly abandoned it. Like the preceding Supreme Court, the 1979 Law on the Supreme Constitutional Court did not include any provisions divesting the Court of legal power over acts of reign or political acts from its jurisdiction. In the foremost few years after its geological formation, the Supreme Constitutional Court followed the policy of the 1969 Supreme Court and abstained from hearing questions concerning acts of reign or political acts. however, the Supreme Constitutional Court finally forsook this approach by narrowing the definition of what actually constituted an act of reign .

The turn point for the Supreme Constitutional Court came in 1986 in a case concerning Article 152 of the egyptian Constitution of 1971, where the Court indicated for the first fourth dimension its abandonment of the abstinence policy. In Case No. 56 of the Sixth Judicial Year ( June 21, 1986 ), citizens brought a claim concerning the constitutionality of Article 4 of Law No. 33 ( 1978 ). The government attempted to dismiss the claim on the basis that the constitutional question at write out was allegedly a political interrogate that fell within the discretion of the Executive Branch. The Supreme Constitutional Court, however, rejected the government ’ second political motion argument and held that “ [ a ] ll statutes which are not constitutional provisions are hyponym to the Constitution, and subject to judicial reappraisal. ”

In abandoning its abstinence policy towards political acts of the Executive Branch, the Supreme Constitutional Court became the most important avenue for political activism challenging autocratic regimes in Egypt for two decades. Under the authoritarian regimen of both Sadat and Mubarak, egyptian judges were able to exercise a meaning degree of independent authority. Despite the billow in independence of the Supreme Constitutional Court into the late 1990s, the Supreme Constitutional Court has lost much of its independence in late years, allowing a firm administrator power to usurp the oversight exponent of the egyptian judiciary .

Having explored the evolution of the historic relationship between the Judicial and Executive Branches, I will now move to Part IV where I will discuss the Supreme Constitutional Court decision passed on March 3, 2018, concerning the cession of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands to Saudi Arabia .

IV. The Constitutionality of the March 2018 Supreme Constitutional Court Decision

In answer to the at odds rulings of the Supreme Administrative Court upholding the injunction on the agreement, and the Court of Urgent Matters subsequently nullifying the injunction, the Supreme Constitutional Court, on June 21, 2017, suspended all proceedings concerning the agreement to await a final examination resoluteness by the Court. Article 192 of the egyptian Constitution of 2014 confers single jurisdiction to the Supreme Constitutional Court to resolve any questions concerning the constitutionality of laws and to resolve any disputes between two conflicting concluding rulings :

The Supreme Constitutional Court shall be entirely competent to decide on the constitutionality of laws and regulations, to interpret legislative provisions, and to adjudicate on disputes pertaining to the affairs of its members, on jurisdictional disputes between judicial bodies and entities that have judicial legal power, on disputes pertaining to the implementation of two final examination contradictory judgments, one of which is rendered by a judicial body or an authority with judicial legal power and the early is rendered by another, and on disputes pertaining to the execution of its judgments and decisions .

The Supreme Constitutional Court asserted in its decision of March 3, 2018, that it is the court “ entirely competent to adjudicate ” the maritime-boundary-limitation treaty between Egypt and Saudi Arabia. however, quite than adjudicate the issue on the merits, the Supreme Constitutional Court used its absolute authority just to negate the rulings made by the Supreme Administrative Court and the Court of Urgent Matters, which it considered as obstacles hindering the execution of the Court ’ sulfur decision :

[ T ] he Court [ has ] the right to remove any obstacles to the execution of the judgment issued, whether such obstacle was legislation or a court judgment. .. [ the two lower court cases ] will not be taken into circumstance. This is because – evening if it is a final court sagacity – it is not more than a fabric obstacle which is equivalent to its

non-existence. .. . and it must be dismissed .

In kernel, the Court avoided addressing the issue of territorial cession by redirecting its focus to the impermissible misdemeanor of the lower courts on administrator world power. nowhere in the decision does the Court always actually address the implicit in unconstitutionality of the maritime-boundary-limitation treaty itself .

The Supreme Constitutional Court based its decisiveness not to intervene on the principle of separation of powers, concluding that the egyptian Constitution “ does not extend judicial oversight of the judicial authority and its branches and courts of the state council over sovereign acts, specially political actions and international conventions and agreements relating to the sovereignty of the state. .. . ” According to the opinion of the Court, such acts of sovereignty are “ held by the executive and legislative authorities and not by the judicial authority. ” The Court distinguished the executive actions that were entirely within the horizon of the Executive Branch from the executive actions that were administrative in nature, which permissibly fell within the horizon of the administrative courts. The decision defined administrator acts of sovereignty as those relating to the Executive ’ s function to achieve the interests of the entire political government and to ensure deference for the Constitution and the supervision of its relations with early states. conversely, the administrative functions of the Executive Branch, which are concerned with overseeing the daily interests of the public and its public facilities, have traditionally been considered reviewable by the administrative courts. Considering the nature of the agreement as one concerning political relations with a alien state, the Supreme Constitutional Court deemed the agreement to fall within the jurisdiction of the former quite than that of the latter .

ultimately, the Court concluded that because of the misdemeanor of the separation of powers by the Supreme Administrative Court and the Court of Urgent Matters, there was no write out on the merits remaining for the Supreme Constitutional Court to adjudicate : “ consequently, this Court has decided not to accept the dispute, since the decision to request a stay of murder of the opinion has become irrelevant. ”

here we see the Supreme Constitutional Court take a significant pace backward from its stance on discriminative reappraisal in the 1978 lawsuit, where the Court basically held that it could review any law short circuit of amending the Constitution. Nevertheless, the most baffling aspect of the Court ’ south opinion is its portrayal of the issue as one that implicates the separation of powers. The transfer of the Tiran and Sanafir Islands to Saudi Arabia is not a question of separation of powers, but, rather, it is a question of constitutionality. There can be no violation on the executive if the Executive Branch is exercising a power outside the scope of its constituent assurance .

The cession of the islands to Saudi Arabia violates three clear-cut provisions of executive power defined in the egyptian Constitution of 2014. Article 139 of the Constitution establishes the role of the President as the forefront of executive world power : “ He shall care for the interests of the people, safeguard the independence of the state and the territorial integrity and safety of its lands, bide by the provisions of the Constitution, and assume his authorities as prescribed therein. ”

beginning, in his capability as President, Sisi is required to “ concern for the interests of the people. ” The agreement to cede the islands to Saudi Arabia was met with far-flung disapproval from the egyptian populace. Within a week after the converge on April 8, 2016, between President Sisi and King Salman, massive protests erupted throughout the area. During the June 2017 protests following Parliament ’ randomness vote approving the agreement, patrol officers assaulted and detained hundreds of protestors and raided the homes of journalists and assorted political party members who opposed the agreement. Prior to the parliamentary consider on the Treaty, sixty-two news sites were blocked, with the number exceeding over one hundred websites and media outlets in the aftermath of the vote. As President, it is Sisi ’ s built-in duty to act on the behalf of the people. however, rather than heed the voices of the public, Sisi responded with violence and draconian censoring towards any opposition to the agreement .

second, the President must “ safeguard the independence of the nation and the territorial integrity and safety of its lands. ” By selling the islands to Saudi Arabia in exchange for $ 22 billion in economic aid, the agreement threatens both the integrity of the nation ’ mho territory, american samoa well as the political autonomy of the country. The Treaty leaves Egypt financially subject on another sovereign department of state, and by extension, renders Egypt politically subordinate to Saudi Arabia.

Read more: Maritime search and rescue – Documentary

Third, as President, Sisi must “ digest by the provisions of the Constitution, and assume his authorities as order therein. ” however, in signing the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement ceding Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia, Sisi has expressly violated Article 151 of the Constitution, which states that “ no treaty may be concluded which is contrary to the provisions of the Constitution or which results in ceding any character of express territories. ” As was established in Part II of this Note, the Tiran and Sanafir Islands distinctly constitute egyptian sovereign nation. Article 151 of the Constitution expressly invalidates any treaty that cedes any part of the egyptian territory. In signing the maritime-boundary-limitation treaty with Saudi Arabia, Sisi has exceeded the scope of his executive authority and has expressly violated the Constitution .

Considering that the Treaty itself and the actions of the President are constitutional violations, the Supreme Constitutional Court has explicit legal power to review these actions under the Constitution. Article 192 of the Constitution expressly grants the Supreme Constitutional Court exclusive legal power “ to decide on the constitutionality of laws and regulations. ” To refrain from addressing these constitutional questions would be to disregard the fundamental purpose of the Supreme Constitutional Court : “ surely, the control of constitutionality has an undeniable legal dimension, which means that the original duty of the judge is to verify the constitutionality of the law required to be applied to the challenge filed before him. ” In choosing to abstain from adjudicating the merits of the agreement, the Supreme Constitutional Court has shirked its built-in duties, careless of whether the Executive and the legislative Branches have approved the Treaty. “ If the evaluate discovers that the decision contradicts the united states constitution, his natural duty is to apply the constitutional planning, the higher law, and to ignore the legislative provision. ” In light of the crying unconstitutionality of the cession, it was the Supreme Constitutional Court ’ s built-in duty to enjoin the maritime-boundary-limitation agreement .

V. Conclusion

The recent agreement to cede the Tiran and Sanafir Islands to Saudi Arabia and the Supreme Constitutional Court ’ s refusal to address the merits of the exit reflect the growing usurpation of judicial might by an increasingly brawny Executive Branch. Although the Supreme Constitutional Court was once a champion of people ’ second rights in Egypt in the face of a succession of authoritarian and draconian regimes, the egyptian judiciary has lost much of its autonomy under Sisi ’ second presidency. not only is the loss of the islands a tragic botch to the national sovereignty of the nation, but it besides marks a meaning regression in the sovereignty of the egyptian people in a post-Revolution Egypt .