The deserve of free trade is a widely debated subject. That said, receptiveness to trade is frequently associated with economic growth. The experiences of South Korea in the postwar period and the recent performance of China are big examples. recent empiric influence using natural experiments that induce larger changes in deal costs for some pairs of countries than others—such as the decline in the cost of shipping goods by air, the settlement of the Suez Canal and the insertion of the steamer 2 —implies big increase effects. 3 yet, quantitative trade models relying on standard static mechanisms imply reasonably belittled gains from openness and, therefore, can not account for emergence miracles or large emergence effects. 4 late study has analyzed an option mechanism : the impact of openness on the creation and dispersion of best practices across countries. 5

A theory of innovation and diffusion in an interconnected world

In our late shape newspaper, 6 we model invention and dissemination as a process involving the combination of new ideas with insights from other industries and countries. Insights occur randomly and result from local interactions among producers. In our theory, openness affects the universe and dispersion of ideas by determining the interactions from which producers draw their insights. Openness affects the set of producers that sell goods within a country, adenine well as the set of technologies used domestically .

In this context, we provide conditions under which the distribution of productiveness among producers within each area converges to a Fréchet distribution, 7 no matter how trade wind barriers shape person producers ’ local interactions. The state of cognition within a area can be summarized by the charge of this distribution, which we call the nation ’ second stock of cognition. furthermore, we show that the change in a state ’ second sprout of cognition can be characterized in terms of entirely its barter shares, its deal partners ’ stocks of cognition, and parameters. The model is frankincense amenable and compatible with the widely used quantitative frameworks that have been useful in studying trade flows in an environment with many asymmetrical countries. 8 consequently, the model both yields qualitative insights and enables us to use actual trade wind flows to discipline the function of trade and geography in shaping estimate flows and growth.

Starting from autarky ( closed borders ), a state opening itself to trade results in a higher temp growth rate and a permanently higher level of the lineage of cognition, as producers are exposed to more generative ideas. We separate the gains from trade into inactive and dynamic components. The electrostatic part consists of the gains from increased specialization and relative advantage, whereas the active component comprises the gains that are made through the flow of ideas .

In an environment in which producers in a state gain insights from those that sell goods to the country, the dynamic gains from reducing trade wind barriers are qualitatively different from the inactive gains. The dynamic gains are largest for countries that are relatively close, whereas the static gains are largest for countries that are already relatively open. For a country with high trade barriers, the marginal imports tend to be made by a foreign producer with high productivity. While the high craft costs imply that the electrostatic gains from barter remain reasonably minor, the insights drawn from these bare producers tend to be of high quality. In contrast, for a country with low trade wind barriers, the reduction in trade costs leads to big inframarginal static gains from trade wind, but the insights drawn from the fringy producers are likely to yield lower productiveness and generate lower-quality ideas .

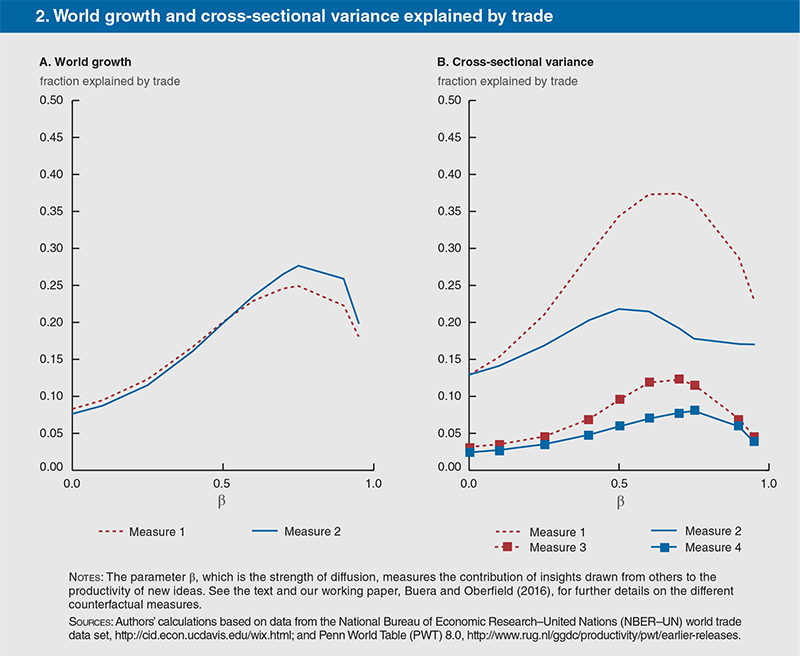

Our model nests, at two extremes, a model of pure invention 9 and a exemplar of pure diffusion. 10 We have our exemplar span these two extremes by varying a single parameter, β, which we label the strength of dissemination. The parameter β measures the contribution of insights from others to the productiveness of new ideas. One hit observation is that for either of these two extremes, if a moderately open nation lowers its trade costs, the resulting moral force gains from trade are fairly belittled, whereas when β is in an intercede range, the active gains are larger. When β is minor therefore that insights from others are, for the most part, unimportant, it follows immediately that moral force gains tend to be small. When β is larger, insights from others are more central. however, in the specify model, as β approaches the extreme of one, a state accrues about all of the moral force gains from trade adenine long as it is not in autarky. A reasonably open state is much better off than it would be in autarky, but promote reductions in trade costs have short affect. As a consequence, it is entirely when β is in an intercede range that the moral force gains from trade are goodly and would result from reductions in trade costs in the empirically relevant scope .

Quantitative exploration

To explore the ability of the theory to account for the development of the universe distribution of productiveness, we specify a quantitative translation of the model that includes nontraded goods and average inputs, equally well as equipped department of labor with capital and department of education. specifically, we use this version of the model to study the ability of the theory to account for cross-country differences in sum gene productiveness ( TFP ) 11 in 1962 and TFP ’ s subsequent evolution through 2000. We use panel data on trade flows and relative prices to calibrate the evolution of bilateral deal costs and take the evolution of population, physical capital and human capital ( i.e., equipped labor ) from the datum. Given the evolution of trade costs and equipped british labour party, our model predicts the evolution of each area ’ south TFP .

Before discussing the results from the calibrate model, we present indicative reduced-form tell of the mechanisms emphasized by the theory, which is evocative of the early evidence discussed in inquiry about the importance of cognition spillovers through deal. 12

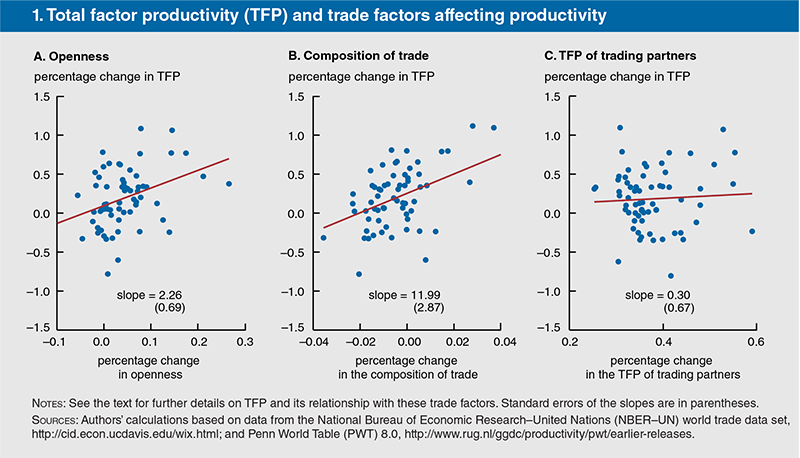

Over time, among the many factors that would alter a nation ’ s productivity, the model emphasizes changes in openness, changing exposure to deal partners, and changes in trading partners ’ TFP. trope 1 shows some simple reduced-form patterns in the datum. Panel A of figure 1 shows the kinship between changes in openness and changes in TFP. Consistent with the exemplar, countries that increased expenditures on imports tended to have ( statistically importantly ) larger increases in TFP. Panel B shows the association between the change in countries ’ composing of barter and TFP emergence. reproducible with the theory, there is a clear convention that countries that increased import exposure to trading partners with high initial productiveness see ( statistically importantly ) larger increases in TFP. last, empanel C shows that countries whose trading partners became more productive tended to see increases in TFP. While this kinship is consistent with the exemplar, it is fairly weak and statistically insignificant .

The predicted relationship between craft and TFP depends on the measure of β ( the strength of dispersion ) —which indexes the contribution of insights drawn from others to the productiveness of new ideas. While we provide a childlike strategy to calibrate this parameter ( β = 0.7 ), our chief approach is to simulate the model for versatile alternative values and explore how well the model can quantitatively account for cross-country income differences and the development of countries ’ productivity over prison term .

In figure 2, we present respective measures of the extent to which changes in trade costs can account for the distribution of TFP growth rates over the period 1962–2000. Panel A of figure 2 focuses on the role of changes in trade costs in accounting for average TFP increase across the earth, while panel B focuses on the fraction of the cross-sectional variance explained by changes in barter costs. In argumentation with our theoretical results, the function of trade in accounting for both the level and distribution of TFP growth rates is highest for average values of the diffusion parameter, β. The versatile lines in the trope correspond to alternative ways of constructing counterfactuals ( see our working newspaper for details 13 ), but the coherent message is that the contribution of trade wind is up to three times as large when the mannequin allows for moral force gains from deal. The quantitative model is quite capable of explaining much of the development of TFP in growth miracles, accounting for over one-third of the TFP growth in China, South Korea, and Taiwan .

Read more: Maritime on Audiotree Live (Full Session)

Conclusion

In our work we provide a amenable theory of the cross-country diffusion of ideas and a quantitative assessment of the character of trade in the infection of cognition across nations. Of course, we omitted many channels that may complement or offset the function of trade wind in the dissemination of ideas. Chief among these is foreign direct investment. indeed, the structure of our model can be naturally embedded in quantitative models of multinational productions. 14 We see this as an arouse avenue for future research .

1 A slenderly different version of this article recently appeared as a column on VoxEU.org, the policy portal vein of the London-based Centre for Economic Policy Research .

3 Earlier knead suggested a strong relationship between trade openness and growth ; see by J. D. Sachs and A. Warner, 1995, “ Economic reform and the action of ball-shaped integration, ” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 1–118 ; D. Dollar, 1992, “ Outward-oriented developing economies truly do grow more quickly : testify from 95 LDCs, 1976–1985, ” Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 40, No. 3, April, pp. 523–544 ; D. Ben-David, 1993, “ Equalizing exchange : Trade liberalization and income convergence, ” quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 108, No. 3, pp. 653–679 ; D. T. Coe and E. Helpman, 1995, “ International R & D spillovers, ” european Economic Review, Vol. 39, No. 5, May, pp. 859–887 ; and J. A. Frankel and D. H. Romer, 1999, “ Does deal cause growth ?, ” american Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, June, pp. 379–399. however, other inquiry has subsequently argued that many estimates in the literature suffered from econometric issues, including omitted variables, endogeneity, and miss of robustness ; see, e.g., F. Rodríguez and D. Rodrik, 2001, “ Trade policy and economic growth : A skeptic ’ s guide to the cross-national evidence, ” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, B. S. Bernanke and K. Rogoff ( eds. ), Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, pp. 261–338. More late contributions to the literature ( mentioned in note 5 ) have developed strategies to overcome some of these issues. For a review of the literature, interpret besides R. E. Lucas, Jr., 2009, “ Trade and the dissemination of the Industrial Revolution, ” american Economic Journal : Macroeconomics, Vol. 1, No. 1, January, pp. 1–25 ; R. Wacziarg and K. H. Welch, 2008, “ Trade liberalization and growth : New tell, ” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 187–231 ; and D. Donaldson, 2015, “ The gains from market consolidation, ” Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 619–647 .

4 M. Connolly and K.-M. Yi, 2015, “ How much of South Korea ’ s growth miracle can be explained by trade policy ?, ” american Economic Journal : Macroeconomics, Vol. 7, No. 4, October, pp. 188–221 .

6 Buera and Oberfield ( 2016 ) .

7 A Fréchet distribution is a character of utmost prize distribution .

8 J. Eaton and S. Kortum, 2002, “ Technology, geography, and craft, ” Econometrica, Vol. 70, No. 5, September, pp. 1741–1779 ; A. B. Bernard, J. Eaton, J. B. Jensen, and S. Kortum, 2003, “ Plants and productiveness in international trade, ” american english Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 4, September, pp. 1268–1290 ; and F. E. Alvarez and R. E. Lucas, Jr., 2007, “ General equilibrium analysis of the Eaton–Kortum model of international trade wind, ” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 54, No. 6, September, pp. 1726–1768 .

9 S. Kortum, 1997, “ Research, patent, and technical switch, ” Econometrica, Vol. 65, No. 6, November, pp. 1389–1419 .

10 F. E. Alvarez, F. J. Buera, and R. E. Lucas, Jr., 2008, “ Models of idea flows, ” National Bureau of Economic Research, working composition, No. 14135, June ; and Alvarez, Buera, and Lucas ( 2013 ) .

11 TFP refers to the technologies and operational systems that businesses use to combine diverse inputs into outputs. In other words, TFP captures the residual growth in sum output of the national economy that can not be explained by the accretion of measured inputs, such as labor movement and das kapital.

Read more: Australia Maritime Strategy

12 Coe and Helpman ( 1995 ) ; and D. T. Coe, E. Helpman, and A. W. Hoffmaister, 1997, “ North–South R & D spillovers, ” Economic Journal, Vol. 107, No. 440, January, pp. 134–149. For a recent review of this empirical literature, which considers alternate channels ( including extraneous direct investment ), see W. Keller, 2009, “ International trade, alien lead investing, and technology spillovers, ” National Bureau of Economic Research, working wallpaper, No. 15442, October .

13 Buera and Oberfield ( 2016 ) .

14 See, for example, N. Ramondo and A. Rodríguez-Clare, 2013, “ Trade, multinational production and the gains from openness, ” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 121, No. 2, April, pp. 273–322 .