It was a blast heard around the earth. news of what happened when two ships collided in the harbor of the historic larboard city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on December 6, 1917, made headlines worldwide. In times of war, accidents happened in busy seaports, and life went on. But this time, things were unlike .

It was a blast heard around the earth. news of what happened when two ships collided in the harbor of the historic larboard city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on December 6, 1917, made headlines worldwide. In times of war, accidents happened in busy seaports, and life went on. But this time, things were unlike .One of the vessels involved in the collision was the SS Imo, a norwegian war-relief ship. The early was SS Mont-Blanc, a rusting french hiker steamer that was loaded with gunwales with high explosives, about 3,000 tons of picric acid, TNT, and artillery cotton, while piled high on her deck were hundreds of barrels of high-octane benzene fuel .

The Mont-Blanc was a float bomb. As one veteran Royal Navy officer would late marvel, “ I ’ m surprised that people on the embark didn ’ triiodothyronine leave in a body when they saw the nature of the cargo she had been ordered to carry ” .

The range of events that put Imo and the Mont-Blanc on a collision course was a improbable as it was bizarre. It defied logic. The upwind was open and balmy. The sea was calm. Veteran seaport pilots were guiding each ship. The Two captains involved were have mariners.

The norwegian ship SS Imo had sailed from the Netherlands en route to New York to take on relief supplies for Belgium, under the control of Haakon From .

The norwegian ship SS Imo had sailed from the Netherlands en route to New York to take on relief supplies for Belgium, under the control of Haakon From .

The ship arrived in Halifax on 3 December for neutral inspection and exhausted two days in Bedford Basin awaiting refuelling supplies. Though she had been given clearance to leave the interface on 5 December, Imo ’ second deviation was delayed because her ember load did not arrive until late that good afternoon .

The french cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc arrived from New York late on 5 December, under the instruction of Aimé Le Medec. He intended to join a slow convoy gather in Bedford Basin readying to depart for Europe but was besides belated to enter the harbor before the nets were raised .

Ships carrying dangerous cargo were not allowed into the harbor before the war, but the risks posed by german submarines had resulted in a relaxation of regulations .

Navigating into or out of Bedford Basin required passage through a strait called the Narrows. Ships were expected to keep close up to the english of the channel situated on their starboard ( “ right ” ), and pass oncoming vessels “ port to port ”, that is to keep them on their “ left ” side. Ships were restricted to a speed of 5 knots ( 9.3 kilometers per hour ; 5.8 miles per hour ) within the harbor .

Shortly before 9:00 am the Imo, headed out of Halifax Harbour and found itself on a collision path with the Mont-Blanc. After exchanging warn signals, both ships had cut their engines, but their momentum carried them correctly on top of each early at slow amphetamine .

Shortly before 9:00 am the Imo, headed out of Halifax Harbour and found itself on a collision path with the Mont-Blanc. After exchanging warn signals, both ships had cut their engines, but their momentum carried them correctly on top of each early at slow amphetamine .

unable to ground his ship for fear of a shock that would set off his explosive cargo, Mackey ( an experienced harbor pilot ) ordered Mont-Blanc to steer hard to port ( starboard helm ) and crossed the bow of Imo in a last-second bid to avoid a collision .

The two ships were about parallel to each other, when Imo on the spur of the moment sent out three signal blasts, indicating the ship was reversing its engines .

The combination of the cargoless ship ’ mho stature in the water and the cross lunge of her right propeller caused the ship ’ s head to swing into Mont-Blanc. Imo ’ randomness bow pushed into the No. 1 defend of Mont Blanc, on her starboard side .

The collision occurred at 8:45 am. The damage to Mont Blanc was not austere, but barrels of deck cargo toppled and broke open. This flooded the deck with benzene that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo ’ s engines kicked in, she disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc ’ s hull. These ignited the vapor from the benzene.

The collision occurred at 8:45 am. The damage to Mont Blanc was not austere, but barrels of deck cargo toppled and broke open. This flooded the deck with benzene that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo ’ s engines kicked in, she disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc ’ s hull. These ignited the vapor from the benzene.

A burn started at the water production line and travelled quickly up the side of the ship. Surrounded by thick black smoke, and fearing she would explode about immediately, the master ordered the crew to abandon embark .

A growing act of Halifax citizens gathered on the street or stand at the windows of their homes or businesses to watch the spectacular fire. The frantic crew of Mont-Blanc shouted from their two lifeboats to some of the other vessels that their ship was about to explode, but they could not be heard above the noise and confusion .

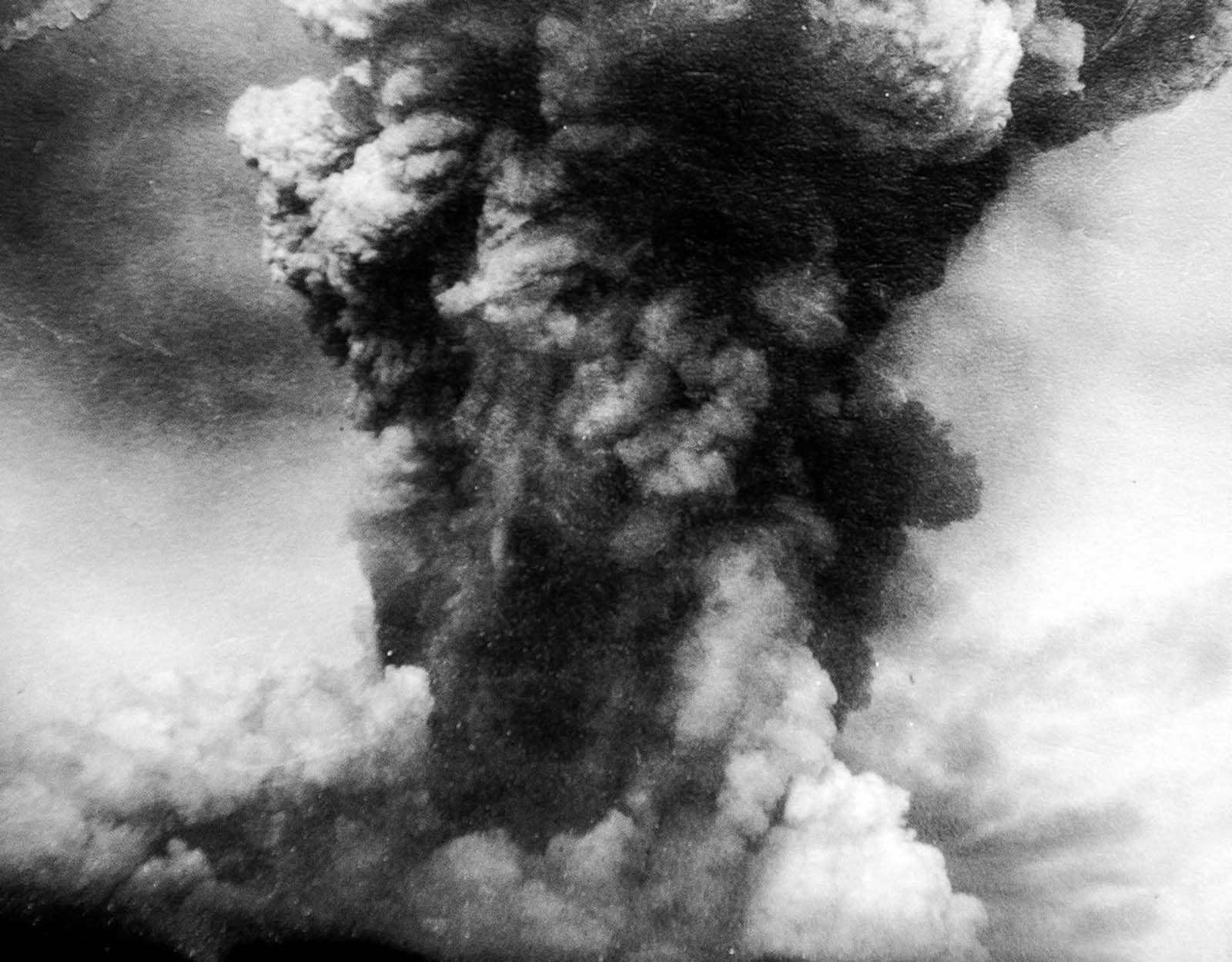

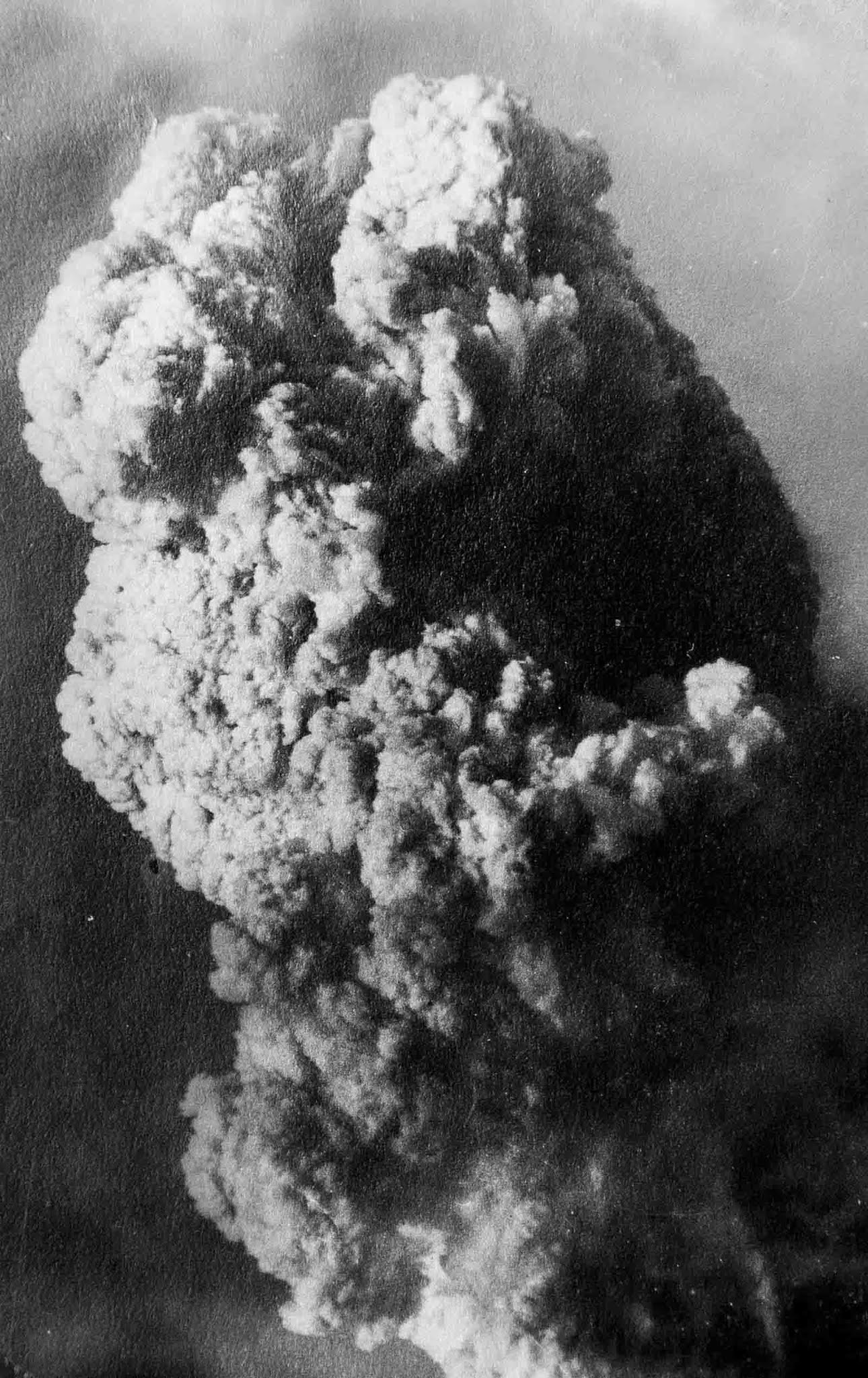

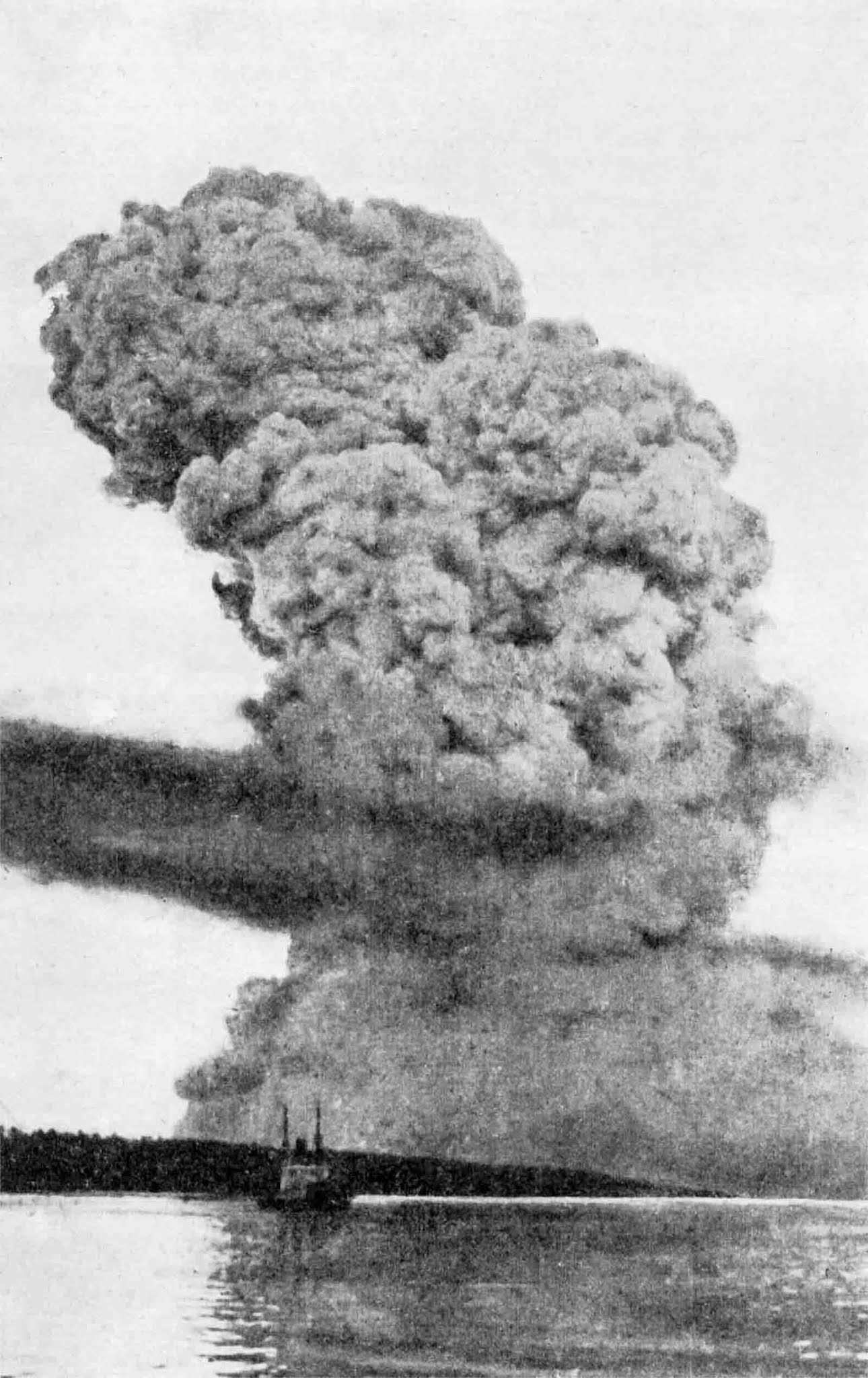

just after 9:04 am, the Mont-Blanc exploded. The ship was wholly blow apart and a powerful blast wave radiated off from the explosion initially at more than 1,000 metres ( 3,300 foot ) per second .

Temperatures of 5,000 °C ( 9,000 °F ) and pressures of thousands of atmospheres accompanied the moment of explosion at the center of the explosion .

white-hot shards of iron fell down upon Halifax and Dartmouth. Mont-Blanc ’ s forward 90-mm gun landed approximately 5.6 kilometres ( 3.5 myocardial infarction ) north of the explosion site near Albro Lake in Dartmouth with its barrel melted away .

A cloud of flannel smoke rose to at least 3,600 metres ( 11,800 foot ) .The blast was felt as far away as Cape Breton ( 207 kilometres or 129 miles ) and Prince Edward Island ( 180 kilometres or 110 miles ) .

A cloud of flannel smoke rose to at least 3,600 metres ( 11,800 foot ) .The blast was felt as far away as Cape Breton ( 207 kilometres or 129 miles ) and Prince Edward Island ( 180 kilometres or 110 miles ) .

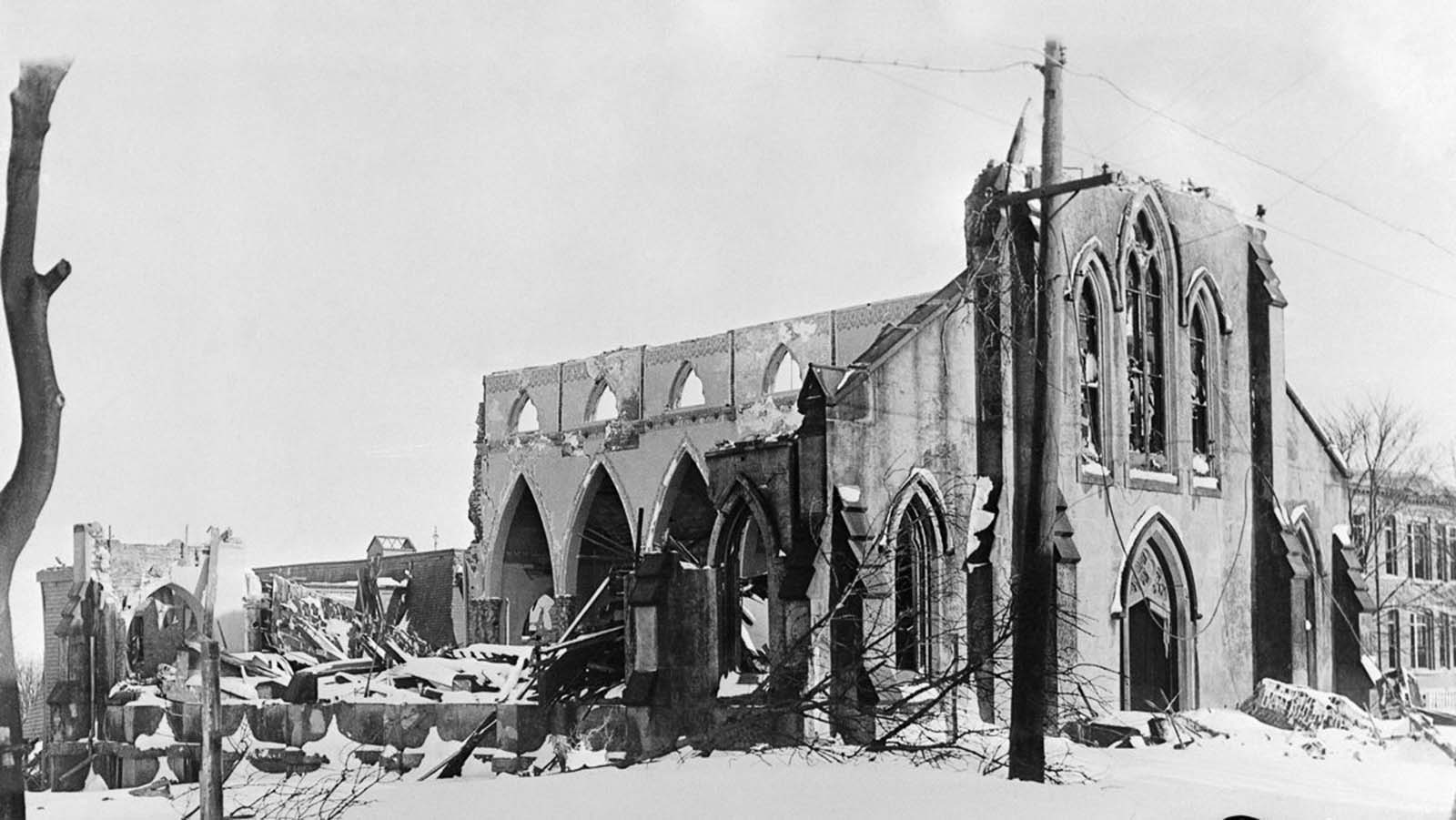

An area of over 160 hectares ( 400 acres ) was wholly destroyed by the explosion, and the harbor floor was momentarily exposed by the volume of water system that was displaced. A tsunami was formed by water surging in to fill the void ; it rose vitamin a high as 18 metres ( 60 foot ) above the high-water mark on the Halifax side of the harbor .

Over 1,600 people were killed immediately and 9,000 were injured, more than 300 of whom belated died. Every construction within a 2.6-kilometre ( 1.6 nautical mile ) radius, over 12,000 in total, was destroyed or badly damaged. ] Hundreds of people who had been watching the fire from their homes were blinded when the smash wave shattered the windows in front of them .

Overturned stoves and lamps started fires throughout Halifax, particularly in the North End, where entire city blocks burned, trapping residents inside their houses .

Firefighter Billy Wells, who was thrown away from the explosion and had his clothes torn from his torso, described the devastation survivors faced : “ The sight was nasty, with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads missing, and some throw onto the overhead telegraph wires. ” He was the only member of the eight-man crew of the fire engine Patricia to survive.

The Halifax Explosion was one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions, releasing the equivalent department of energy of roughly 2.9 kilotons of TNT ( 12 TJ ) .

An extensive comparison of 130 major explosions by Halifax historian Jay White in 1994 concluded that it “ remains undisputed in overall magnitude deoxyadenosine monophosphate long as five criteria are considered together : total of casualties, force of blast, radius of ravaging, quantity of explosive material, and total prize of place destroyed. ”

( Photo credit : Nova Scotia Archives / Library and Archives Canada / Wikimedia Commons / The Halifax explosion : Canada ’ s Worst Disaster ) .

( Photo credit : Nova Scotia Archives / Library and Archives Canada / Wikimedia Commons / The Halifax explosion : Canada ’ s Worst Disaster ) .