The Manila galleons ( spanish : Galeón de Manila ; Filipino : Galyon ng Maynila ) were spanish trade ships which for two and a half centuries linked the spanish Captaincy General of the Philippines with New Spain across the Pacific Ocean, making one or two round-trip voyages per year between the ports of Acapulco and Manila, which were both depart of New Spain. The name of the galleon changed to reflect the city that the transport sailed from. [ 1 ] The condition Manila galleon can besides refer to the trade route itself between Acapulco and Manila, which lasted from 1565 to 1815 .

The Manila galleons sailed the Pacific for 250 years, bringing to the Americas cargoes of lavishness goods such as spices and porcelain in change for New World silver. The road besides fostered cultural exchanges that shaped the identities and culture of the countries involved. The Manila galleons were besides ( reasonably bewilderingly ) known in New Spain as La Nao de la China ( “ The China Ship ” ) on their voyages from the Philippines because they carried by and large chinese goods, shipped from Manila. [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

Reading: Manila galleon – Wikipedia

The spanish inaugurated the Manila galleon deal road in 1565 after the augustinian friar and navigator Andrés de Urdaneta pioneered the tornaviaje or return path from the Philippines to Mexico. Urdaneta and Alonso de Arellano made the first gear successful round trips that year. The barter using “ Urdaneta ‘s route ” lasted until 1815, when the Mexican War of Independence broke out. In 2015 the Philippines and Mexico began preparations for the nomination of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade Route in the UNESCO World Heritage List, with backing from Spain. Spain has besides suggested the tri-national nomination of the Archives on the Manila-Acapulco Galleons in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register .

history [edit ]

discovery of the route [edit ]

In 1521, a spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan sailed west across the Pacific using the westbound deal winds. The expedition discovered the Mariana Islands and the Philippines and claimed them for Spain. Although Magellan died there, one of his ships, the Victoria, made it binding to Spain by continuing westbound .

Acapulco in 1628, Mexican terminus of the Manila galleon

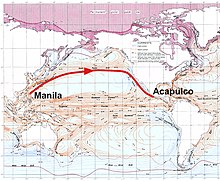

Acapulco in 1628, Mexican terminus of the Manila galleon northerly deal route as used by eastbound Manila galleons In holy order to settle and trade with these islands from the Americas, an eastbound maritime return path was necessity. The Trinidad, which tried this a few years by and by, failed. In 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón besides tried sailing east from the Philippines, but could not find the eastward-blowing winds ( “ westerlies “ ) across the Pacific. In 1543, Bernardo de la Torre besides failed. In 1542, however, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo helped pave the way by sailing north from Mexico to explore the Pacific coast, reaching as far north as the Russian River, merely north of the 38th parallel. The frustration of these failures is shown in a letter sent in 1552 from portuguese Goa by the spanish missionary Francis Xavier to Simão Rodrigues asking that no more fleets attempt the New Spain–East Asia route, lest they be lost. [ 4 ] The Manila–Acapulco galleon craft last began when spanish navigators Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the eastbound restitution path in 1565. Sailing as part of the dispatch commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi to conquer the Philippines in 1564, Urdaneta was given the undertaking of finding a recurrence road. Reasoning that the trade wind winds of the Pacific might move in a coil as the Atlantic winds did, they sailed north, going all the way to the 38th twin union, off the east coast of Japan, before catching the westerlies that would take them back across the Pacific. He commanded a vessel which completed the eastward voyage in 129 days ; this marked the opening of the Manila galleon trade. Reaching the west seashore of North America, Urdaneta ‘s ship, the San Pedro, hit the coast near Santa Catalina Island, California, then followed the shoreline south to San Blas and late to Acapulco, arriving on October 8, 1565. [ 7 ] Most of his crowd died on the long initial voyage, for which they had not sufficiently provisioned. Arellano, who had taken a more south wind route, had already arrived. The English privateer Francis Drake besides reached the California coast, in 1579. After capturing a spanish ship heading for Manila, Drake turned north, hoping to meet another spanish prize ship coming south on its return from Manila to Acapulco. He failed in that attentiveness, but staked an english claim somewhere on the northerly California slide. Although the transport ‘s log and other records were lost, the formally accept placement is now called Drakes Bay, on Point Reyes south of Cape Mendocino. [ a ] [ 16 ] By the eighteenth century, it was silent that a less northerly track was sufficient when nearing the north american seashore, and galleon navigators steered well clear of the rocky and often fogbound northerly and central California seashore. According to historian William Lytle Schurz, “ They generally made their landfall well down the coast, somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas … After all, these were pre-eminently merchant ships, and the commercial enterprise of exploration ballad outside their field, though find discoveries were welcomed ”. [ 17 ] The inaugural motivation for domain exploration of contemporary California was to scout out potential means stations for the seaworn Manila galleons on the last peg of their travel. early proposals came to little, but in 1769, the Portola expedition established ports at San Diego and Monterey ( which became the administrative center field of Alta California ), providing condom harbors for returning Manila galleons .

northerly deal route as used by eastbound Manila galleons In holy order to settle and trade with these islands from the Americas, an eastbound maritime return path was necessity. The Trinidad, which tried this a few years by and by, failed. In 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón besides tried sailing east from the Philippines, but could not find the eastward-blowing winds ( “ westerlies “ ) across the Pacific. In 1543, Bernardo de la Torre besides failed. In 1542, however, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo helped pave the way by sailing north from Mexico to explore the Pacific coast, reaching as far north as the Russian River, merely north of the 38th parallel. The frustration of these failures is shown in a letter sent in 1552 from portuguese Goa by the spanish missionary Francis Xavier to Simão Rodrigues asking that no more fleets attempt the New Spain–East Asia route, lest they be lost. [ 4 ] The Manila–Acapulco galleon craft last began when spanish navigators Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the eastbound restitution path in 1565. Sailing as part of the dispatch commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi to conquer the Philippines in 1564, Urdaneta was given the undertaking of finding a recurrence road. Reasoning that the trade wind winds of the Pacific might move in a coil as the Atlantic winds did, they sailed north, going all the way to the 38th twin union, off the east coast of Japan, before catching the westerlies that would take them back across the Pacific. He commanded a vessel which completed the eastward voyage in 129 days ; this marked the opening of the Manila galleon trade. Reaching the west seashore of North America, Urdaneta ‘s ship, the San Pedro, hit the coast near Santa Catalina Island, California, then followed the shoreline south to San Blas and late to Acapulco, arriving on October 8, 1565. [ 7 ] Most of his crowd died on the long initial voyage, for which they had not sufficiently provisioned. Arellano, who had taken a more south wind route, had already arrived. The English privateer Francis Drake besides reached the California coast, in 1579. After capturing a spanish ship heading for Manila, Drake turned north, hoping to meet another spanish prize ship coming south on its return from Manila to Acapulco. He failed in that attentiveness, but staked an english claim somewhere on the northerly California slide. Although the transport ‘s log and other records were lost, the formally accept placement is now called Drakes Bay, on Point Reyes south of Cape Mendocino. [ a ] [ 16 ] By the eighteenth century, it was silent that a less northerly track was sufficient when nearing the north american seashore, and galleon navigators steered well clear of the rocky and often fogbound northerly and central California seashore. According to historian William Lytle Schurz, “ They generally made their landfall well down the coast, somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas … After all, these were pre-eminently merchant ships, and the commercial enterprise of exploration ballad outside their field, though find discoveries were welcomed ”. [ 17 ] The inaugural motivation for domain exploration of contemporary California was to scout out potential means stations for the seaworn Manila galleons on the last peg of their travel. early proposals came to little, but in 1769, the Portola expedition established ports at San Diego and Monterey ( which became the administrative center field of Alta California ), providing condom harbors for returning Manila galleons .

The Manila galleon and California [edit ]

Monterey, California was about two months and three weeks out from Manila in the eighteenth hundred, and the galleon tended to stop there 40 days before arriving in Acapulco. Galleons stopped in Monterey prior to California ‘s colonization by the spanish in 1769 ; however visits become regular between 1777 and 1794 because the Crown ordered the galleon to stop in Monterey. [ 18 ]

Trade [edit ]

White represents the route of the Manila Galleons in the Pacific and the flota in the Atlantic. ( blue represents portuguese routes. ) Trade with Ming China via Manila served a major source of gross for the spanish Empire and as a fundamental source of income for spanish colonists in the Philippine Islands. Galleons used for the trade between East and West were crafted by Filipino artisans. [ 19 ] Until 1593, two or more ships would set sail annually from each port. [ 20 ] The Manila trade became so lucrative that Seville merchants petitioned king Philip II of Spain to protect the monopoly of the Casa de Contratación based in Seville. This led to the pass of a rule in 1593 that set a specify of two ships sailing each year from either port, with one keep in reserve in Acapulco and one in Manila. An “ armada ”, or armed see of galleons, was besides approved. Due to official attempts at controlling the galleon trade, contraband and understate of ships ‘ cargoes became far-flung. [ 21 ]

White represents the route of the Manila Galleons in the Pacific and the flota in the Atlantic. ( blue represents portuguese routes. ) Trade with Ming China via Manila served a major source of gross for the spanish Empire and as a fundamental source of income for spanish colonists in the Philippine Islands. Galleons used for the trade between East and West were crafted by Filipino artisans. [ 19 ] Until 1593, two or more ships would set sail annually from each port. [ 20 ] The Manila trade became so lucrative that Seville merchants petitioned king Philip II of Spain to protect the monopoly of the Casa de Contratación based in Seville. This led to the pass of a rule in 1593 that set a specify of two ships sailing each year from either port, with one keep in reserve in Acapulco and one in Manila. An “ armada ”, or armed see of galleons, was besides approved. Due to official attempts at controlling the galleon trade, contraband and understate of ships ‘ cargoes became far-flung. [ 21 ]

The galleon trade was supplied by merchants largely from port areas of Fujian, such as Quanzhou, as depicted in the Selden Map, and Yuegang ( the old port of Haicheng in Zhangzhou, Fujian ), [ 22 ] [ 23 ] who traveled to Manila to sell the Spaniards spices, porcelain, bone, lacquerware, processed silk fabric and other valuable commodities. Cargoes varied from one ocean trip to another but often included goods from all over Asia : tire, wax, gunpowder and silk from China ; amber, cotton and rugs from India ; spices from Indonesia and Malaysia ; and a variety of goods from Japan, the spanish separate of the alleged Namban trade, including fans, chests, screens, porcelain and lacquerware. [ 24 ] Galleons transported the goods to be sold in the Americas, namely in New Spain and Peru arsenic good as in european markets. East Asia deal primarily functioned on a silver medal standard due to Ming China ‘s use of silver ingots as a medium of switch over. As such, goods were by and large bought by silver mined from New Spain and Potosí. [ 21 ] In addition, slaves from versatile origins were transported from Manila. [ 25 ] The cargoes arrived in Acapulco and were transported by estate across Mexico. Mule trains would carry the goods along the China Road from Acapulco inaugural to the administrative kernel of Mexico City, then on to the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were loaded onto the spanish care for fleet apprenticed for Spain. The transport of goods overland by porters, the house of travelers and sailors at hostel by innkeepers, and the stock of long voyages with food and supplies provided by hacienda before departing Acapulco helped to stimulate the economy of New Spain. [ 26 ] The barter of goods and exchanges of people were not limited to between Mexico and the Philippines in that Guatemala, Panama, Ecuador, and Peru besides served as supplementary streams to the main one between Mexico and Philippines. [ 27 ]

goal of the Galleons [edit ]

In 1740, as character of the administrative changes of the Bourbon Reforms, the spanish crown began allowing the use of file ships or navíos de registro in the Pacific that traveled solo outside of the convoy system of the galleons. While these solo voyages would not immediately replace the galleon organization, they were more effective and better able to avoid being captured by the Royal Navy. [ 30 ]

Read more: Maritime search and rescue – Documentary

The Manila-Acapulco galleon trade wind ended in 1815, a few years before Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. After this, the spanish Crown took direct dominance of the Philippines, and governed immediately from Madrid. Sea ecstasy became easier in the mid-19th century upon the invention of steam power ships and the open of the Suez Canal, which reduced the travel time from Spain to the Philippines to 40 days .

Galleons [edit ]

construction [edit ]

spanish galleon between 1609 and 1616, 9 galleons and 6 galleys were constructed in Philippine shipyards. The average cost was 78,000 philippine peso per galleon and at least 2,000 trees. The galleons constructed included the San Juan Bautista, San Marcos, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, Angel de la Guardia, San Felipe, Santiago, Salbador, Espiritu Santo, and San Miguel. “ From 1729 to 1739, the independent aim of the Cavite shipyard was the construction and outfitting of the galleons for the Manila to Acapulco barter run. ” [ 31 ] due to the route ‘s high profitableness but long voyage time, it was necessity to build the largest potential galleons, which were the largest class of european ships known to have been built until then. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] In the sixteenth century, they averaged from 1,700 to 2,000 tons [ which? ] [ clarification needed ], were built of Philippine hardwoods and could carry 300 – 500 passengers. The Concepción, wrecked in 1638, was 43 to 49 m ( 141 foot 1 in to 160 ft 9 in ) long and displacing some 2,000 tons. The Santísima Trinidad was 51.5 megabyte ( 169 foot 0 in ) long. Most of the ships were built in the Philippines and only eight in Mexico .

spanish galleon between 1609 and 1616, 9 galleons and 6 galleys were constructed in Philippine shipyards. The average cost was 78,000 philippine peso per galleon and at least 2,000 trees. The galleons constructed included the San Juan Bautista, San Marcos, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, Angel de la Guardia, San Felipe, Santiago, Salbador, Espiritu Santo, and San Miguel. “ From 1729 to 1739, the independent aim of the Cavite shipyard was the construction and outfitting of the galleons for the Manila to Acapulco barter run. ” [ 31 ] due to the route ‘s high profitableness but long voyage time, it was necessity to build the largest potential galleons, which were the largest class of european ships known to have been built until then. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] In the sixteenth century, they averaged from 1,700 to 2,000 tons [ which? ] [ clarification needed ], were built of Philippine hardwoods and could carry 300 – 500 passengers. The Concepción, wrecked in 1638, was 43 to 49 m ( 141 foot 1 in to 160 ft 9 in ) long and displacing some 2,000 tons. The Santísima Trinidad was 51.5 megabyte ( 169 foot 0 in ) long. Most of the ships were built in the Philippines and only eight in Mexico .

Crews [edit ]

Sailors averaged age 28 or 29 while the oldest were between 40 and 50. Ships pages were children who entered military service largely at age 8, many orphans or inadequate taken from the streets of Seville, Mexico and Manila. Apprentices were older than the pages and if successful would be certified a bluejacket at age 20. Because mortality rates were high with ships arriving in Manila with a majority of their crew often dead from starvation, disease and abject, specially in the early years, spanish officials in Manila found it difficult to find men to crew their ships to return to Acapulco. many indios of Filipino and Southeast Asian origin made up the majority of the crew. other crew were made up of deportees and criminals from Spain and the colonies. many criminals were sentenced to serve as crew on imperial ships. Less than a one-third of the crew was spanish and they normally held key positions on board the galleon. [ 34 ] At larboard, goods were unloaded by dockworkers, and food was often supplied locally. In Acapulco, the arrival of the galleons provided seasonal workplace, as for dockworkers who were typically free black men highly paid for their back break labor, and for farmers and haciendas across Mexico who helped stock the ships with food before voyages. On land, travelers were much housed at hostel or mesones, and had goods transported by muleteers, which provided opportunities for autochthonal people in Mexico. By providing for the galleons, spanish colonial America was tied into the broader global economy. [ 26 ]

Shipwrecks [edit ]

The wrecks of the Manila galleons are legends second lone to the wrecks of care for ships in the Caribbean. In 1568, Miguel López de Legazpi ‘s own ship, the San Pablo ( 300 tons ), was the first Manila galleon to be wrecked en route to Mexico. Between the years 1576 when the Espiritu Santo was lost and 1798 when the San Cristobal (2) was lost there were twenty Manila galleons [ 35 ] wrecked within the Philippine archipelago. In 1596 the San Felipe was wrecked in Japan. The cargo was seized by the japanese authorities and the behavior of the crew prompted persecution against the Christians. At least one galleon, probably the Santo Cristo de Burgos, is believed to have wrecked on the coast of Oregon in 1693. Known as the Beeswax wreck, the consequence is described in the oral histories of the Tillamook and Clatsop, which suggest that some of the crowd survived. [ 36 ] [ 37 ] [ 38 ] between 1565 and 1815, 108 ships operated as Manila galleons, of which 26 were lost at sea for respective reasons, including four captured by the enemy ( english or british ) in wartime : the Santa Anna captured in 1587 by Thomas Cavendish, the Encarnacion captured by the british 1709, the Nuestra Senora de la Covadonga captured in 1743 by George Anson, and the Nuestra Senora de la Santisima Trinidad captured in 1762 by the HMS Panther and HMS Argo. [ 31 ]

Over 250 years, there were hundreds of Manila galleon crossings of the Pacific Ocean between contemporary Mexico and the Philippines, with their route taking them merely south of the hawaiian Islands on the westward branch of their attack trip and even there are no records of touch with the Hawaiians. british historian Henry Kamen maintains that the Spanish did not have the ability to properly explore the Pacific Ocean and were not capable of finding the islands which lay at a latitude 20° north of the westbound galleon route and its currents. [ 39 ] however, spanish exploration in the Pacific was paramount until the late eighteenth century. spanish navigators discovered many islands including Guam, the Marianas, the Carolines and the Philippines in the North Pacific, deoxyadenosine monophosphate well as Tuvalu, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Easter Island in the South Pacific. spanish navigators besides discovered the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos during their search for Terra Australis in the seventeenth hundred .

This navigational action poses the question as to whether spanish explorers did arrive in the hawaiian Islands two centuries before Captain James Cook ‘s first visit in 1778. Ruy López de Villalobos commanded a fleet of six ships that left Acapulco in 1542 with a spanish boater named Ivan Gaetan or Juan Gaetano aboard as original. Depending on the interpretation, Gaetano ‘s reports seem to describe either the discovery of Hawaii or the Marshall Islands in 1555. [ 40 ] If it was Hawaii, Gaetano would have been one of the first Europeans to find the islands .

implicated seven foreigners who landed eight generations earlier at Kealakekua Bay in a painted gravy boat with an awning or canopy over the austere. They were dressed in dress of white and yellow, and one wear a sword at his side and a feather in his hat. On bring, they kneeled down in prayer. The Hawaiians, most helpful to those who were most helpless, received them kindly. The strangers ultimately married into the families of chiefs, but their names could not be included in genealogies ”. [ 40 ]

Some scholars, particularly american, have dismissed these claims as lacking credibility. [ 42 ] [ 43 ] Debate continues as to whether the hawaiian Islands were actually visited by the spanish in the sixteenth century [ 44 ] with researchers like Richard W. Rogers looking for evidence of spanish shipwrecks. [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Preparations for UNESCO nominations [edit ]

In 2010, the Philippines foreign affairs secretary organized a diplomatic reception attended by at least 32 countries, for discussions about the historic galleon trade and the possible institution of a galleon museum. diverse mexican and Filipino institutions and politicians besides made discussions about the importance of the galleon trade in their share history. [ 47 ] In 2013, the Philippines released a documentary regarding the Manila galleon trade route. [ 48 ] In 2014, the theme to nominate the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade Route as a World Heritage Site was initiated by the Mexican and Filipino ambassadors to UNESCO. Spain has besides backed the nomination and suggested that the archives related to the route under the monomania of the Philippines, Mexico, and Spain be nominated as separate of another UNESCO list, the memory of the World Register. [ 49 ] In 2015, the Unesco National Commission of the Philippines ( Unacom ) and the Department of Foreign Affairs organized an technical ‘s touch to discuss the trade route ‘s nominating speech. Some of the topics presented include the spanish colonial shipyards in Sorsogon, subaqueous archeology in the Philippines, the route ‘s influences on Filipino textile, the galleon ‘s eastward tripper from the Philippines to Mexico called tornaviaje, and the diachronic dimension of the galleon trade wind focusing on important and rare archival documents [ 50 ] In 2017, the Philippines established the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Museum in Metro Manila, one of the necessary steps in nominating the trade wind route to UNESCO. [ 51 ] In 2018, Mexico reopened its Manila galleon gallery at the Archaeological Museum of Puerto Vallarta, Cuale. [ 52 ] In 2020, Mexico released a documentary regarding the Manila galleon trade path. [ 53 ]

Read more: A Man Quotes Maritime Law To Avoid Ticket

See besides [edit ]

Notes [edit ]

- ^[8] and “most likely”[9][10][11][12] Drake landing site. The National Park System Advisory Board Landmarks Committee sought public comments on the Port of Nova Albion Historic and Archaeological District Nomination [13] and received more than two dozen letters of support and none in opposition. At the Committee’s meeting of November 9, 2011 in Washington, DC, representatives of the government of Spain, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Congresswoman Lynn Wolsey all spoke in favor of the nomination: there was no opposition. Staff and the Drake Navigators Guild’s president, [14] but no additional comments were received. At the Board’s meeting on December 1, 2011 in Florida, the Nomination was further reviewed: the Board approved the nomination unanimously. On October 16, 2012 Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar signed the nomination and on October 17, 2012, The Drakes Bay Historic and Archaeological District was formally announced as a new National Historic Landmark.[15] The Drakes Cove site began its review by the National Park Service ( NPS ) in 1994, therefore starting an 18-year study of the hint Drake sites. The first formal nomination to mark the Nova Albion web site at Drake ‘s Cove as a National Historic Landmark was provided to NPS on January 1, 1996. As part of its review, NPS obtained mugwump, confidential comments from professional historians. The NPS staff concluded that the Drake ‘s Cove site is the “ most probable ” and “ most probably ” Drake landing web site. The National Park System Advisory Board Landmarks Committee sought public comments on the Port of Nova Albion Historic and Archaeological District Nominationand received more than two twelve letters of support and none in resistance. At the Committee ‘s meet of November 9, 2011 in Washington, DC, representatives of the government of Spain, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Congresswoman Lynn Wolsey all spoke in party favor of the nomination : there was no opposition. Staff and the Drake Navigators Guild ’ s president, Edward Von five hundred Porten, gave the presentation. The nomination was strongly endorsed by Committee Member Dr. James M. Allan, Archaeologist, and the Committee as a whole which approved the nominating speech unanimously. The National Park System Advisory Board sought further populace comments on the Nomination, but no extra comments were received. At the Board ‘s meeting on December 1, 2011 in Florida, the Nomination was far review : the Board approved the nomination unanimously. On October 16, 2012 Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar signed the nominating speech and on October 17, 2012, The Drakes Bay Historic and Archaeological District was formally announced as a new National Historic Landmark .

References [edit ]

further read [edit ]

- Bjork, Katharine. “The Link that Kept the Philippines Spanish: Mexican Merchant Interests and the Manila Trade, 1571–1815.” Journal of World History vol. 9, no. 1, (1998) 25–50.

- Carrera Stampa, Manuel. “La Nao de la China.” Historia Mexicana 9 no. 33 (1959) 97-118.

- Fish, Shirley. The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific, with an Annotated List of the Transpacific Galleons 1565–1815. Central Milton Keynes, England: Authorhouse 2011.

- Gasch-Tomás, José Luis. The Atlantic World and the Manila Galleon: Circulation, Market, and Consumption of Asian Goods in the Spanish Empires, 1565-1650. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

- Giraldez, Arturo. The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- Luengo, Josemaria Salutan. A History of the Manila-Acapulco Slave Trade, 1565–1815. Tubigon, Bohol: Mater Dei Publications 1996.

- McCarthy, William J. “Between Policy and Prerogative: Malfeasance in the Inspection of the Manila Galleons at Acapulco, 1637.” Colonial Latin American Historical Review 2, no. 2 (1993) 163–83.

- Oropeza Keresey, Deborah. “Los ‘indios chinos’ en la Nueva España: la inmigración de la Nao de China, 1565–1700.” PhD dissertation, El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Históricos, 2007.

- Rogers, R. (1999). Shipwreck of Hawai’i: a maritime history of the Big Island. Haasdasdleiwa, Hawfasfasfaii: Piliagagasgaloha Pub. ISBN 0967346703

- Schurz, William Lytle. (1917) “The Manila Galleon and California”, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 107–126

- Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939.