Technical considerations: a wider lens for finer detail

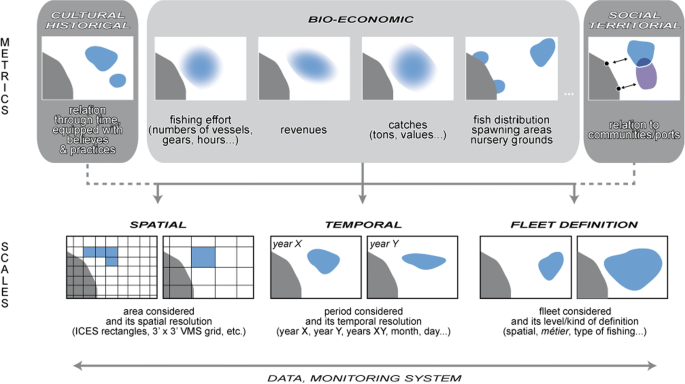

The utility of maps is determined by their floor of detail and resolution, and for MSP, sufficient resoluteness is necessity to represent what are both explicit and implicit details that characterise marine sectors, in this case fisheries. In this section, we produce a conventional to discuss the want for a wide position on fisheries to include early metrics including social and cultural data, equally well as tackle the spatial-temporal elements ( Fig. 1 ). Datasets should include information about polish, such as the presence of cultural inheritance, traditions, beliefs and practices that constitute the fishing sector. furthermore, local attachment to quad, vitamin a well as the identity of fishing communities and the social networks which determine the types of relations both at ocean and inshore ( e.g. with grocery store traders ) are all valuable facets that require recognition in MSP. such data is necessary because social and cultural values are equivalently important as economic ones ( Urquhart et al., 2013 ). such data would be particularly utilitarian in the future, where policymakers would need to assign quad to new uses in a way that does not put into conflict existing uses ( Brown et al., 2015 ). apart from reduce income for the fish sector, impacts are likely to create ripple effects on other systems of the local anesthetic economy, including sectors subject on local pisces products ( restaurants, hotels, processing plants ). With deoxidize socio-cultural traits in fish harbor, the tourism sector besides stands out to lose ( Jacob et al., 2010 ) .Fig. 1 Multi-component analysis to define fisheries. reference : authors

Multi-component analysis to define fisheries. reference : authors

Full size double In terms of ‘ scale ’ of the fish action, we highlight the want for data on the fleet definition. its spatial extent, a well as the temporal resolution. This datum would help us better understand what type of fishing is occurring—the gearing involved, the species targeted, the scale of activity ( minor, large-scale, amateur ), relations between crew-members—and how fishers interplay within heterogeneous fishing fleets, and with other marine activities. By this, we mean taking into report the spatiotemporal plate of the natural process to represent the frequency and volume of use of a detail area by understanding ( iodine ) the clock time of operations, ( two ) the space of mathematical process, and ( three ) the type of fishing activeness as illustrated in Fig. 1. This can be challenging for boats that are not equipped with vessel monitoring systems ( the count of which is quite high ) ; however, early data such as interviews and participatory moral force map could be used to provide these details, as will be promote illustrated in the “ political considerations : an inclusive lens for deeper fisheries knowledge ” section. Having such data would besides enable an in-depth sympathy of both existing conflict hotspots and potential compatibilities both within fishing and between fish and other activities, including, for model, the electric potential for low-impact fisheries to sit in conservation areas as recognized by Jones ( Jones, 2009 ) or the coexistence of fishing and dive ( Habtemariam & Fang, 2016 ). This would then enable better plan of activities within the MSP, such as electric potential temporal multiple-use schemes, e.g. ‘ dive during the day ’ and ‘ fish during the night ’ in areas contested by both diving and fishing. Challenges like the one described above are common in coastal areas, which tend to be congested with competing activity, and which highlight the want for data that can help us decide which activities need to be abolished, and what can stay and under which terms. Through this multi-component analysis, it would be possible to anticipate winners and losers of possible planning scenarios, and determine either systems of recompense or alternative approaches to assigning space. such data is very relevant as it maps out the complexity of what could late become stumbling blocks to the plan action due to lack of acceptance by the affect stakeholders. Through ‘ Deep Knowledge ’, we are able to construct model that are dynamic—just as real biography at ocean is—and thus counter the deficiencies of current inactive representation. This march would benefit from invention of data types theatrical performance such as 3D or 4D map and geovisualisation tools which could better represent spatiotemporal variability of such multi-component datasets in the plan region ( Andrienko et al., 2008 ; Kraak & Ormeling, 2010 ; Resch et al., 2014 ; Roth, 2013 ; Salter et al., 2009 ; van den Brink et al., 2007 ) .

Political considerations: an inclusive lens for deeper fisheries knowledge

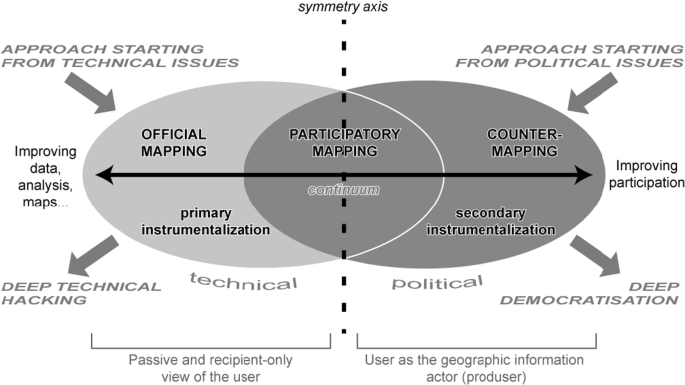

Inclusivity and stakeholder participation is a fundamental component of any MSP march ( Douvere & Ehler, 2009 ), and while many countries do implement engagement strategies, there are distillery concerns about the degree to which political considerations shape this process. In this section, we highlight the indigence for broader political considerations in MSP in both the mapping ( and data collection ) and planning stages. We argue that map and plan processes should be regarded as two sides of the lapp coin if they are to achieve effective inclusiveness, thus giving authenticity to the process that decides which information is collected and for which determination. Drawing on Budhathoki et alabama. ( Budhathoki et al., 2008 ) and Haklay ’ second ( Haklay, 2013 ) late work on mapping systems, we suggest revising the way engagement structures are implemented and orchestrated to influence mapping and design processes.

Read more: What is the Maritime Industry?

In Fig. 2, we conceptualize the unlike types of engagement processes available. On one side, ‘ Technical Hacking ’ involves a technocratic approach determined by a work of ‘ Official Mapping ’ which by and large aims at improving the characteristics of data and maps and their analysis, without very questioning how they fit into the ‘ bigger ’ design. It is besides in lineage with a broader drift of neogeography ( Haklay, 2013 ) or citizen sciences contesting official producers of data, whether voluntarily or not. On the other pass, ‘ Deep Democratization ’ is conceptualized as a political approach configured around an overall design, finish or strategy, and thus aims to cater for the interests of stakeholders by opening up the ability of social intervention beyond its usual field, in especial by bringing the technical aspects of data product close to the political debates based on the datum themselves. In bare words, the technical set about focuses on the means ( mapping ), while the political one is interested in the ends ( planning ) .Fig. 2 Finding a way between technical and political approaches of function Full size effigy

Finding a way between technical and political approaches of function Full size effigy

Read more: What is the Maritime Industry?

We contend that in many cases, official MSP is largely delivered by abstruse ‘ technical hack ’, where managerial-technical cognition producers are given a mandate to map and plan fisheries, but not to influence, sketch, or intervene politically. science, from this perspective, comes to appear as confused and complimentary of politics. here, we call for deeper cognition that invites more political leverage and which thus incorporates multiple knowledges both in the map and planning stages. specifically, we argue that governments ( or their state-appointed experts ) should not be alone in determining what legitimate and utilitarian cognition is. rather, such duty should be shared with the different stakeholders including fishers, leading to the impression of ‘ producer ’ ( Budhathoki et al., 2008 ). In other words, and referring to Fig. 2, the process requires a travel from ‘ Official Mapping ’ as controlled by deep technical foul hack to an inclusive one where the political and technical considerations are identified jointly, not individually. In practice, this would mean doing aside with current two-stage systems whereby government first collects data and maps, then invites stakeholders to debate policy, denying the latter a ‘ say ’ on how maps are produced and with which cognition types. Finding the middle-ground ‘ participatory map ’ would embrace both technical and political considerations, giving fishers ( supported by scientists ) the ability to collect data and to map their activities themselves, such that they can represent their stakes. The experimental activity conducted by Trouillet et alabama. ( Trouillet et al., 2019 ) —where fishers were invited to produce their own maps—testifies towards the success that inclusivity and deep cognition can have when the political interface is allowed to play a role through enhance participation in the technical build-up of data. here, we see the role of fishers not as participants in the data collection process, or receive guests for debates on planning, but as ‘ producers ’ of cognition in a process that captures and valorises diverse knowledges. In this smell, the ‘ cryptic cognition ’ theme underlines the importance of merging the ability to participate with the ability to hold cognition, and to communicate it. Through the right interface, the knowledges of fishers are mobilized to a degree that can be interpreted and incorporated within the decision-making framework ( Madrigal-Ballestero et al., 2013 ). By providing the means to fishers to actually become the owners and leaders of their own data process, they could become empowered not entirely to determine the type, style and width of the data but besides to use this tool as a political instrument to partake in decision-making fora with their own ‘ scientific ’ datum ( Trouillet et al., 2019 ). Through their engagement, fishers can provide function of their forte uses, define spatial uses and frequency, identify zones of local social, cultural and economic importance, and ease up information about hotspots and conflicts that would require specific solution strategies in the milieu of nautical spatial policy planning ( De la Cruz Modino & Pascual-Fernández, 2013 ). The particularities of certain conflicts—such as those between different activities, or inter-sectoral tensions between fishers using different gear—are crucial, for they contribute to the ‘ bigger picture ’ and illuminate the challenges and resilience of fisheries ( Said et al., 2017 ). such data could besides simulate potential access implications that fishers could face due to increased activities competing for maritime space, equally well as the likely affect of displace fish efforts to neighbouring fishing grounds. failure to recognize current and at hand realities can lead to spatial plans that do not misfit, misrepresent, and misunderstand the real context they mean to govern. For example, in the marine planning of marine protected areas ( MPA ) in different countries, fishers ended up compress between industrial fishers on the one and conservation objectives on the other, leaving fishermen no other option but to resist governmental policy in wish to pursue their livelihoods ( Begossi et al., 2011 ; Said et al., 2017 ; Lopes et al., 2015 ). Being aware of these multiple knowledge layers makes planners better equipped to reflect on the deeper ramifications that lie beneath the surface of the spatial plan, and to frankincense to make ‘ informed ’ MSP decisions .