The War of 1812: Stoking the Fires

summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2

Impressment of Seaman Charles Davis by the U.S. Navy

By John P. Deeben

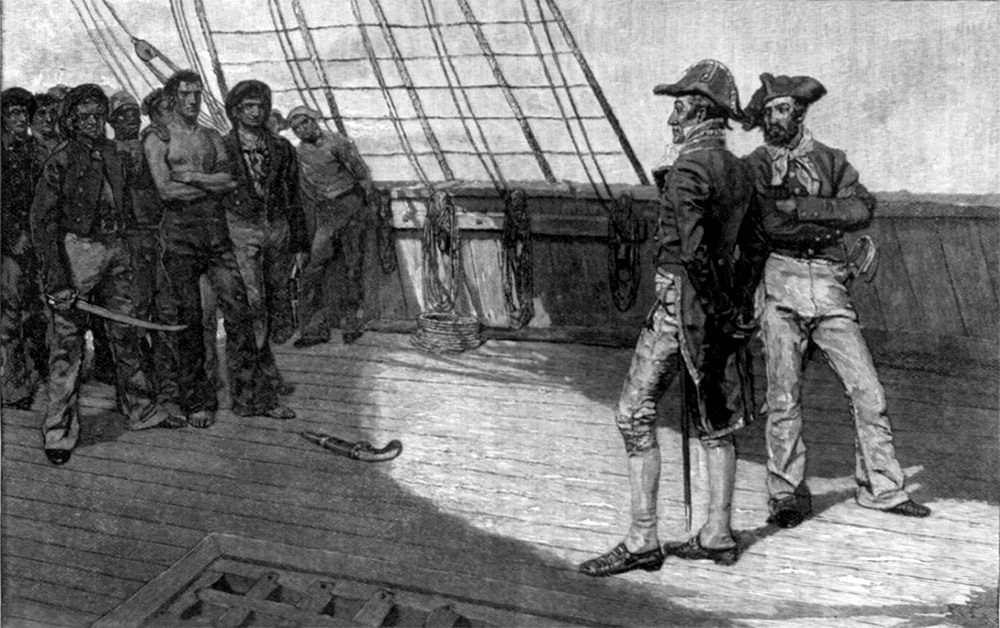

British officers inspect a group of American sailors for impressment into the British navy, ca. 1810, in a drawing by Howard Pyle. The practice angered Americans and was one cause of the War of 1812. But American naval officers engaged in the same practice against British sailors. (Library of Congress) british officers inspect a group of american sailors for impress into the british dark blue, ca. 1810, in a pull by Howard Pyle. The practice angered Americans and was one induce of the War of 1812. But american english naval officers engaged in the like practice against british sailors. ( Library of Congress ) On the night of November 12, 1811, the 36-gun british frigate HMS Havannah lay anchored at Spithead, a sheltered pass near the naval harbors of Portsmouth and Gosport in Hampshire, England. Spithead served as one of the principal bases for the Royal Navy along the English Channel, and the Havannah, as a member of the Channel Fleet, regularly patrolled the area, watching for french vessels from Brest or Le Havre attempting to infiltrate coastal waters.

Reading: The War of 1812: Stoking the Fires

In the darkness, the deck watch on the spur of the moment heard splashing sounds and spotted a figure in the water swimming madly toward them. Dropping a longboat from the gunwales, crewmen pulled aboard what they initially thought was an american deserter from the nearby frigate USS Constitution, which had recently put into Spithead for a courtesy call or to take on supplies. rather, the drench man identified himself as Irish seaman Charles Davis ; he claimed to have good escaped from forced servitude in the United States Navy .

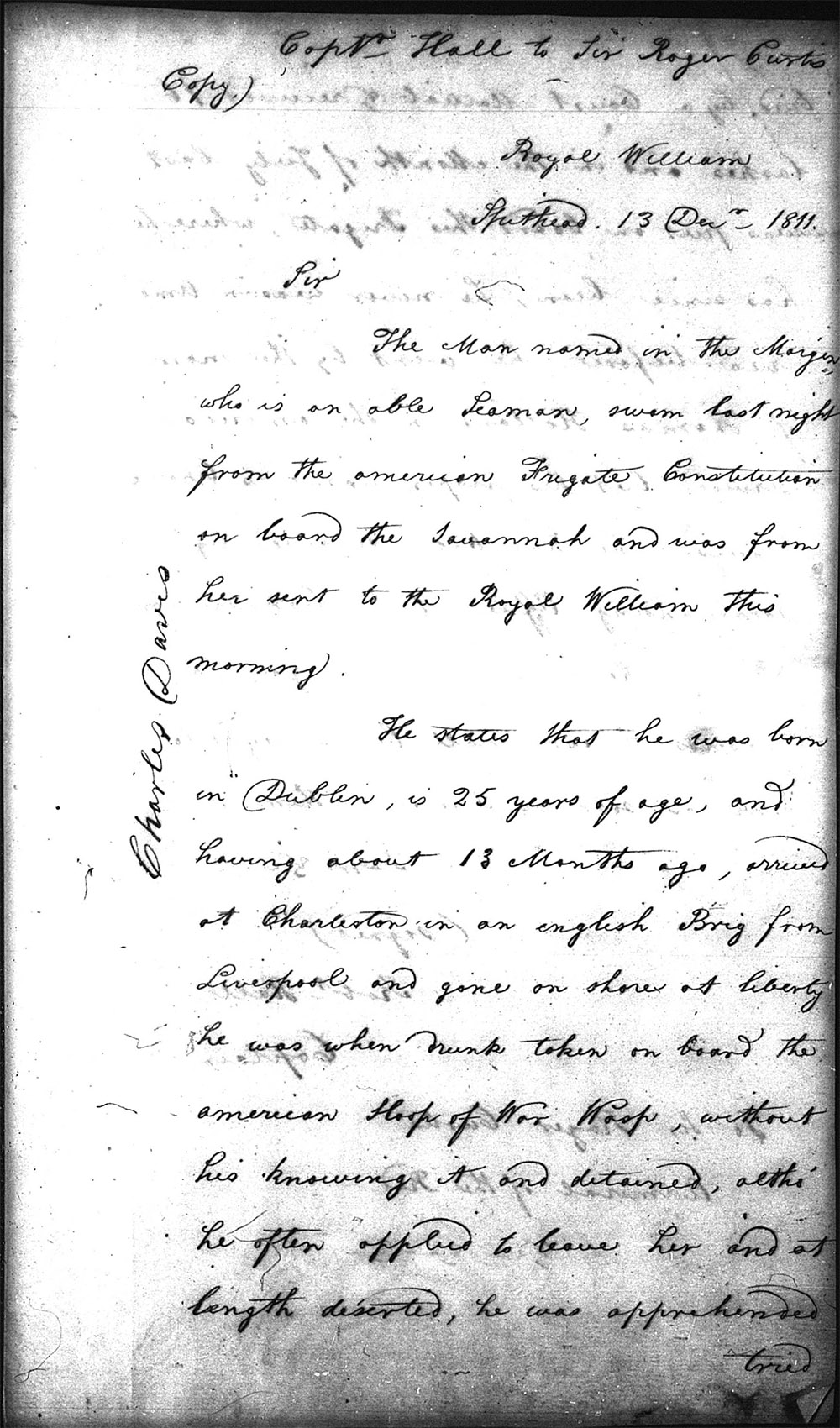

Davis subsequently recounted his ordeal to Capt. Robert Hall of the HMS Royal William, who communicated the incidental to Adm. Sir Roger Curtis, commander-in-chief of the naval station at Portsmouth. In his composition, Hall reiterated the pivotal affirmation that Davis “ never was in America before. .. he has been detained by the command officeholder of the Constitution. ”. It appeared to be a acquit sheath of extraneous impress ; however, there is little evidence to suggest anything promote came of the incident in diplomatic circles, even though procedures were in place at that time to lodge a ball charge with the United States politics. ( Since 1796, an american agent had been stationed in London to investigate impress issues and secure the release of American victims ). But for the fact that a copy of Hall ‘s report finally found its direction into the general records of the U.S. State Department—along with a few early documents about shanghai seamen of british origin—the ordeal of Charles Davis might have faded into history .

The impress or forcible seizure of american seamen by the british Royal Navy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries has traditionally been viewed as a chief causal agent of the War of 1812. Americans at that time regarded impress as a debate and dastard dissemble perpetrated by a alien power against innocent men. Although modern scholars now question the true extent and impingement of the practice as a precursor to war—between 1789 and 1815, the british impressed fewer than 10,000 Americans out of a sum population of 3.9 to 7.2 million—impressment however stoked popular indignation, provoking Congress into legislative military action and raising diplomatic tensions with Britain. The experience of Charles Davis, however, illuminates a lesser known view about american blameworthiness in the hale impress issue. To a certain extent ( and obviously not widely admitted by american officials ), the United States reciprocated impress against the british, seizing unsuspecting seamen to serve aboard american warships .

A British Maritime Tradition Collides with American Ideals

Impressment constituted a longstanding nautical tradition in Great Britain, a prerogative held by the Crown following centuries of development ( report instances of impress occurred arsenic early as the Anglo-Saxon period, followed by extensive usage from the Elizabethan era to the Commonwealth years under Oliver Cromwell ). As Britain evolved into a solid oceangoing nation, the Royal Navy gradually viewed impress as a lawful method acting of recruitment. When necessary, naval authorities orchestrated press gangs in british ports under the guise of the “ impress service. ” Headed by a naval recruit officer, the service hired local anesthetic ruffians to comb the wall countryside for suitable recruits in central for traveling expenses and a fee for each draftee. apparently, the gangs lone targeted british subjects, including Royal Navy deserters and inhabitants of coastal areas who excelled in such necessary seafaring skills as r-2 and sail make, seafaring, and embark carpentry. By the eighteenth century, Britain came to regard impress as a nautical right and extended the commit to boarding neutral merchant ships in local waters and at ocean .

In the 1790s, impress became even more important as the outbreak of war between Britain and France in the wake island of the french Revolution spawned a awful need for a much larger united states navy. between 1793 and 1812, Parliament increased the size of the Royal Navy from 135 to 584 ships and expanded personnel from 36,000 to 114,000 seamen. By contrast, work force in the british merchant nautical in 1792 already stood at 118,000, reflecting a detectable preferment for civilian over military service. The Royal Navy had a venerable and ill-famed repute for hanker voyages, harsh discipline, and poor compensation—sailors ‘ wages were frequently withheld for at least six months to discourage desertions—which paled in comparison to the more humane conditions in the civilian merchant fleet ( where everyone ‘s wellbeing hinged upon the success and profitableness of each voyage ). In reply to the recruit disparity, impress became a full of life cock .

Capt. Isaac Hull, famed master of the USS Constitution, engaged in impressment of British sailors, as did many other American officers. (Library of Congress) Capt. Isaac Hull, famed master of the USS Constitution, engaged in impress of british sailors, as did many other american officers. ( Library of Congress ) The commit, however, immediately drew Britain into ideological conflict with the recently established government of the United States. Tempered by generations of local self dominion and individual freedoms—reflected decidedly in the Declaration of Independence, the recent cathartic experience of the american english Revolution, and the result Constitution and Bill of Rights—the United States strenuously disavowed impress as an external mighty. The solid nature and aim of press gangs represented an diss to human rights and national reign ; the act of forcing individuals to serve a extraneous ability against their will was an “ arbitrary loss ” of personal familiarity barren of the due process of jurisprudence .

This perceived scoff of freedom on the part of the British besides clashed immediately with America ‘s emerging attitude regarding the rights of neutrals on the high sea. International maritime jurisprudence at that time limited the extent of home sovereignty to a country ‘s warships and territorial waters, which often left civilian fleets vulnerable on the open seas. The holiness and assurance of a state ‘s flag did not necessarily exempt its merchantmen from aggression by belligerents engaged in the established rules of war, which allowed enemy goods, contraband, and personnel to be seized wherever they might be found. Nations at war frankincense asserted the right to stop and search impersonal ships as a matter of course. Britain aggressively pursued such a policy as it waged open war at ocean with France in the 1790s, invoking the properly of impress in the process .

conversely, the United States, attempting to assert itself as an emerging naval office, not entirely championed the right of neutrals to engage in complimentary trade with belligerents at war but besides believed that disinterest protected all persons sailing under a sovereign flag regardless of national lineage. As Secretary of State James Madison observed in 1804 to James Monroe, who was then serving as U.S. curate to Great Britain, “ We consider a achromatic flag on the high seas as a safeguard to those sailing under it. .. . [ N ] owhere will she [ Great Britain ] find an exception to this exemption of the seas, and of neutral ships, which justifies the taking aside of any person not an enemy in military service, found on board a achromatic vessel. ” The right field of visitation and search, Americans maintained, should allow for a casual examen of a vessel ‘s papers or manifest but preclude the capture of neutral civilians .

U.S. opposition to impressment increased dramatically as Britain ‘s growing need for able sailors quickly exposed the apparent vulnerability of american seamen. even though they disavowed any desire to impress U.S. citizens, the british openly claimed the right to take british deserters from american ships. ( quite frequently, british seamen composed 35 to 40 percentage of U.S. naval crews in the early nineteenth hundred, enticed to serve by better pay and working conditions ). obvious similarities in culture and terminology complicated efforts to distinguish between american english and British-born seamen as well, leading to frequent instances of wrongful impress. Acknowledging the problem in 1792, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson observed, “ The commit in Great Britain of impressing seamen whenever war is apprehended will fall more heavily on ours, than on those of any other extraneous nation, on account of the monotony of terminology. ”

On May 28, 1796, Congress finally passed legislation ( 1 Stat. 477 ) to counteract the impress threat. Intended to identify and repatriate american victims, the act authorized the government to appoint agents to investigate impress incidents and pursue legal means to obtain the release of the seamen. Masters of american ships at ocean had to report incidents of impress to the customs agentive role at the nearest american larboard, or to lodge a “ protest ” with the U.S. consulate if an impress took place in a alien port. An act of March 2, 1799 ( 1 Stat. 731 ), besides required the submission of annual reports to Congress regarding impress action. In the midst of this official american english reaction against the perceive horrors and injustice of impress, however, similar behavior on the share of the U.S. Navy obviously occurred with little notice or gossip. The attempt to document american impress cases ironically allowed the atrocities perpetrated against Charles Davis and other british seamen finally to come to light adenine well .

Turning the Tables: The Ordeal of Charles Davis

Charles Davis was born in the parish of St. Mary ‘s in Dublin, Ireland, about 1786. In 1795, at the age of nine, he was apprenticed to a Dublin mariner named Edward Murphy, the master of a merchant vessel called the Valentine. Murphy taught the young lad the basic aspects of the seafaring deal for two years and then sent Davis to sea on respective merchant vessels for hardheaded experience. One ocean trip tied drew Davis into the nefarious universe of the Atlantic slave barter, when he sailed on the slave ship Princess Amelia from Liverpool to the seashore of Africa and then to Santo Domingo and Grenada in the West Indies. While docked at the port of Antigua with the merchant brig Ann in February 1807, Davis experienced impress for the first time when he was abducted by the HMS St. Lucia. That ordeal ended after two french privateers captured the british schooner. Davis last returned to Liverpool in August 1807, where he worked in the dockyards as a rigger for about three years .

Capt. Robert Hall of the HMS Royal William recorded the testimony of British sailor Charles Davis in November 1811, after Davis escaped impressment on board the USS Constitution. Hall recounted the incident in his report to Adm. Sir Roger Curtis, commander-in-chief of the naval station at Portsmouth. (General Records of the Department of State, RG 59) Capt. Robert Hall of the HMS Royal William recorded the testimony of British boater Charles Davis in November 1811, after Davis escaped impress on control panel the USS Constitution. Hall recounted the incident in his report to Adm. Sir Roger Curtis, commander-in-chief of the naval station at Portsmouth. ( cosmopolitan Records of the Department of State, RG 59 ) On August 5, 1810, Davis went second to ocean on the merchant transport Margaret for what would prove to be his final civilian ocean trip. The Margaret brought Davis to America ( contrary to his claim in the Hall report ) for the first time on October 2, landing at the port of Charleston, South Carolina. After four days aboard ship, Davis and three shipmates went ashore to a local tavern. By his own entrance fee, Davis imbibed excessively much and could not recall what happened next, except that “ on the follow morning he found himself on control panel the American United States sloop of war Wasp. .. he does not know by what means he was put on display panel her. ” suddenly finding himself addressed as seaman Thomas Holland, Davis immediately applied to First Lieutenant Ingles of the Wasp to be returned to the Margaret, pointing out that he was british rather than an american english citizen. Ingles bluffly refused, stating that he would see Davis “ drowned foremost, ‘for the english keep the Americans and I will keep you. ‘ ”

therefore began 13 months of forced labor in the U.S. Navy under an assume mention. The Wasp cruised for a time along the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, during which Ingles put Davis in irons on several occasions for refusing to work and threatening to jump transport at the first opportunity. On November 20, 1810, he ultimately succeeded in slipping his chains after the Wasp returned to Charleston harbor. Swimming to shore, Davis walked 124 miles to Savannah where, unfortunately, another Charleston tavern keeper recognized him ( his abandonment had been well publicized by the captain of the Wasp ) and caused Davis to be arrested. After Davis returned to the Wasp, the captain placed him in double irons for 72 days. For attempting to desert, Davis was besides court-martial and sentenced to 78 lashes with a cat-o-nine tails, with the punishment to be administered on control panel the USS John Adams in Hampton Roads, Virginia .

Around the clock of his trial and punishment ( Davis never explained the accurate time frame of the corrective legal action ), the USS Constitution arrived at Hampton Roads in July 1811 to seek a draft of new men for her crew. Capt. Isaac Hull of the Constitution boarded the John Adams doubly to requisition crewmembers while Davis was even on dining table. At first, Hull rejected Davis because of his nationality, which suggested there was indeed some cogency to the latter ‘s claim of being held illegitimately on the naval ship. After returning for a second look, however, Hull decided to take Davis, reportedly commenting : “ I do not care a bloody lease you be english or what you will. I will run the gamble of taking you. ” With Captain Hull ‘s pronouncement, Charles Davis boarded the Constitution on July 27 and began the voyage that finally ended with his dramatic escape at Spithead on November 12, 1811.

Read more: What is the Maritime Industry?

Clues Revealed about U.S. Impressment Activities

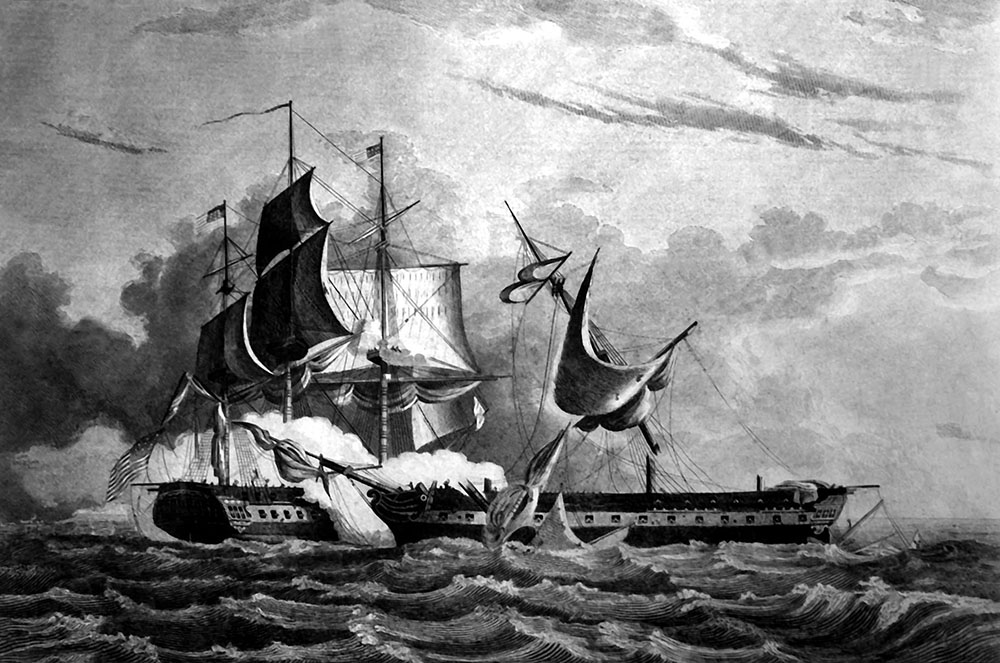

The USS Constitution defeats HMS Guerriere, August 19, 1812. (127-N-302108) The USS Constitution defeats HMS Guerriere, August 19, 1812. ( 127-N-302108 ) Limited information about british victims makes it unmanageable to estimate the full oscilloscope of impressments perpetrated by the U.S. Navy. As one of the more detail survive cases, however, the ordeal of Charles Davis surely suggests a few generalities about the nature of american english impress activities. First, Davis ‘s experience indicates that some well-known american naval commanders willingly engaged in the rehearse, in particular Isaac Hull, who later helmed the Constitution to its celebrated victory against HMS Guerriere during the War of 1812. Hull ‘s actions mirrored an earlier incidental involving another rising naval officer, William Bainbridge. As the youthful captain of a civilian merchant vessel in 1796—two years anterior to his appointment as a Navy lieutenant—Bainbridge retaliated against the impress of one of his crewmembers by the HMS Indefatigable by seizing an english sailor from the future merchant vessel he came upon in open waters. This sequence, enhanced even more when Bainbridge openly announced his intentions to the English ocean captain, cemented his late naval reputation .

second, american complicity in press gang activity appeared to be widespread, rivaling some of the State Department ‘s countless evidence about american victims. Davis alluded to the being of many other british victims in his own testimony to Admiralty officials, asserting “ there are about 60 or 70 H.B.M. [ His Britannic Majesty ‘s ] subjects now on board the said embark Constitution. .. he does not know their names but he believes they would come ahead and own themselves as such subjects if any officer was to claim them. ” Davis noted in particular that numerous “ forecastle men have told him they were Englishmen, ” many of whom “ expressed. .. a hope to get away from the Constitution. ” Another british mariner, William Bowman, who was pressed into the U.S. Navy in New York on or about June 4, 1811, alike reported “ there were a great many English on display panel ” the USS Hornet, “ respective of whom would be beaming to quit her. ”

not amazingly, U.S. Navy records are sufficiently obscure about the demand nature of force recruitments. Muster rolls for the USS Wasp simply show that Charles Davis, aka Thomas Holland, first appeared on control panel at Charleston on October 25, 1810, and late transferred to the USS Constitution for detached service on July 27, 1811. Without knowing the early side of the narrative, the records appear to document a typical enlistment. Likewise, the deck log of the Constitution noted the learning of newly crewmembers on July 27—including 10 pursers, 2 quartermasters, 29 seamen, and 32 ordinary seamen—but suggested nothing contentious about the nature of the transfers. The only specific reference to Davis ‘s ordeal appeared in the Constitution ‘s log for November 13, 1811, when the deck officer noted at “ 1/2 past 8 post meridiem an officeholder came aboard from the Havannah frigate and said they had taken up a man which had swam from the Constitution. It proved to be Thomas Holland, a seaman. ”

british sailors besides apparently faced discussion of equal ferociousness at the hands of the Americans, despite the prevail perception of better conditions in the U.S. Navy. Davis competently illustrated several methods of harsh punishment in his own fib, including placement in irons for long periods of time for resisting authority and lashings with a cat-o-nine tails for attempting desertion. similarly, Bowman, after being taken aboard the Hornet, faced the menace of undetermined punishment for contacting his wife after the american english warship arrived at Cowes, an english seaport on the Isle of Wight, near the port of Southampton. When Elizabeth Elinor Bowman came to the Hornet to see her husband, the american officers treated her with adequate crudeness. At inaugural, they refused to allow Elizabeth on board and then only granted her a half-hour visit. Afterward, the officers denied Elizabeth permission to leave and detained her for several days .

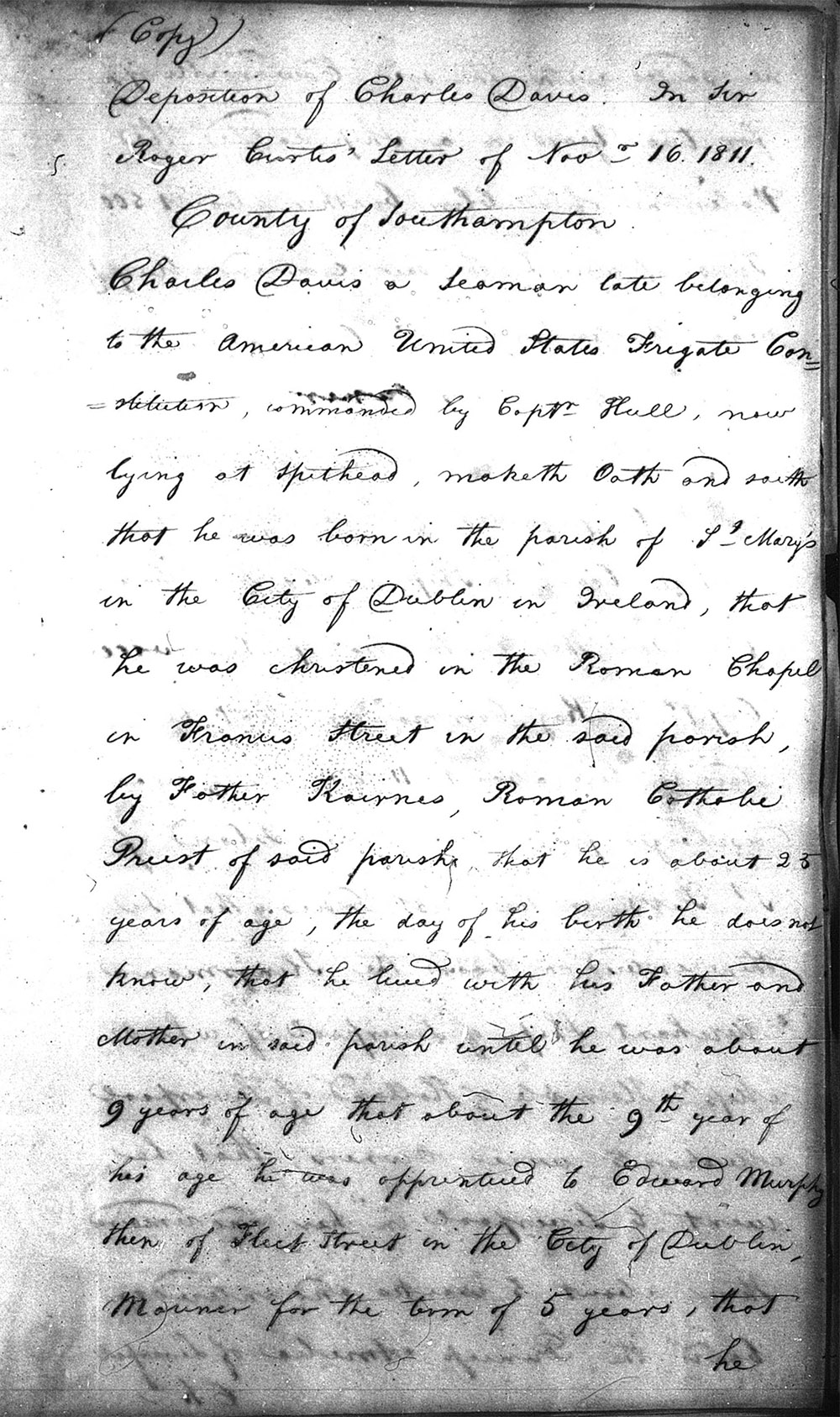

The opening page of Charles Davis s deposition on November 16, 1811, after his escape from the USS Constitution. (General Records of the Department of State, RG 59) The opening page of Charles Davis mho deposition on November 16, 1811, after his elude from the USS Constitution. ( general Records of the Department of State, RG 59 ) The manner in which Davis wound up in american english hands suggests the U.S. Navy besides engaged in the tactic of “ shanghaiing ” likely victims for compulsory service at ocean. Although the term itself became more normally associated with later nautical kidnappings along the California coast in the 1850s, this allegedly democratic method acting of impress involved snatching incapacitated victims from dives and hostels in local seaports ( specially after they had been intentionally drugged or intoxicated ). After getting drink in at a Charleston tavern on the nox of October 6, 1811, and ineffective to explain how he late found himself aboard the USS Wasp, Davis subsequently learned that the actual Thomas Holland, the owner of the tavern, had in fact delivered him to the crew of the Wasp soon after Davis passed out. For unknown reasons, Holland gave his own name to the crowd when he presented his “ recruit, ” causing Davis to serve under the alias “ Thomas Holland ” during his stallion prison term with the U.S. Navy. While it is impossible to determine if Davis was intentionally drugged, his report still intimates the possibility of collusion between the tavern custodian and American naval personnel and likewise demonstrates that some U.S. officers willingly took advantage of impaired sailors to bolster their crews .

A final aspect of the Davis subject suggests a similarity between british and american efforts to document impress incidents against each other. In a manner comparable to the U.S. State Department ‘s instructions to compile lists and depositions about american victims, the british Board of Admiralty—the supervisory authority over the Royal Navy in the early 19th century—made taxonomic attempts to solicit firsthand evidence and official commensurateness regarding the impress of british sailors. Davis ‘s detailed testimony and accompanying letters between Adm. Sir Roger Curtis and John Wilson Croker, first repository to the Admiralty, demonstrated a methodical effort to implement directives of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty and obtain seasonably information from british sailors who escaped American warships. Curtis even acquired evidence about the discipline of William Bowman ( readily supplied by his wife, Elizabeth ) while the latter was still detained aboard the USS Hornet in January 1812 .

* * * *

The experience of Charles Davis—filled with details of questionable motives, tactics, and treatment—highlighted american english blameworthiness as an equally pitiless player in the unharmed offspring of naval impress. Although the United States took a decidedly exalted stance against the nautical commit, insisting on the democratic rights of seamen and sovereign vessels of all nationalities on the high seas—an ideal that finally drew the U.S. government into a second base war with Great Britain in 1812—evidence of ambidextrous behavior on the function of the American naval establishment surely existed. In the end, impress proved to be a normally accept rehearse, possibly evening a necessary evil, among nautical powers in an age of everyday war on the senior high school seas. The ordeal of Charles Davis simply highlighted the other side of a disruptive issue in America ‘s seafaring history, revealing useful insights about ordinary seamen living through extraordinary times .

John P. Deeben is a genealogy archives specialist in the Research Support Branch at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. He earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and Pennsylvania State University, respectively .

Note on Sources

identical few general studies about the history of impress have been produced in scholarly circles, the most utilitarian being a 1960 reprint of a 1925 dissertation by James Fulton Zimmerman, Impressment of american Seamen ( New York : Columbia University Press, 1925 ), which gives the figure of fewer than 10,000 Americans being impressed. A few general histories of the War of 1812 besides touch on the discipline, including Bradford Perkins, Prologue to War : England and the United States, 1805–1812 ( Berkeley : University of California Press, 1968 ) ; Reginald Horsman, The Causes of the War of 1812 ( Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962 ) ; and Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812 : A Forgotten Conflict ( Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1989 ). Hickey has besides dealt more recently with quarrel facts and misconceptions about impress and other issues in Do n’t Give Up the ship ! Myths of the War of 1812 ( Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2006 ). The episode about William Bainbridge ‘s impress activities is recounted in Joseph Wheelan, Jefferson ‘s War : America ‘s First War on Terror, 1801–1805 ( New York : Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003 ) .

The Charles Davis impress deposition, dated November 15, 1811, is reproduced in National Archives Microfilm Publication M1839, Lists and Miscellaneous Papers Relating to impress Seamen, 1796–1814. This issue besides includes related agreement of the british officials who investigated the Davis lawsuit, including letters from Capt. Robert Hall, HMS Royal William, to Adm. Sir Roger Curtis, commander-in-chief, Portsmouth, dated November 13, 1811, and Curtis to John Wilson Croker, secretary to the Board of Admiralty, dated January 25, November 16, and December 20, 1811. besides quoted is a relate deposition from Elizabeth Elinor Bowman, wife of print seaman William Bowman, dated January 25, 1812. These records are all share of the subgroup “ Records Relating to impress Seamen, 1793–1815, ” in Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State. Muster rolls for the USS Wasp and USS Constitution are reproduced in National Archives Microfilm Publication T829, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, while the Constitution deck logs are located in Microfilm Publication M1030, Logbooks and Journals of the U.S.S. Constitution, 1798–1934 .

References to U.S. legislation about affect seamen include “ An Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen, ” April 28, 1796, U.S. Statutes at Large, 4th Congress, 1 : 477 ; and “ An Act to Revive and Continue in Force Certain Parts of the ‘Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen, ‘ and to Amend the Same, ” March 2, 1799, U.S. Statutes at Large, 4th Congress, 1 : 731. Quotations from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison regarding the negative impingement of impress on american citizens and the rights of neutrals on the high seas are from american State Papers, Foreign Relations, 1 : 131 ( Thomas Jefferson to George Washington, February 7, 1792 ) and 2 : 730 ( James Madison to James Monroe, January 5, 1804 ) .

The writer has previously researched aspects of impress and available records at the National Archives and Records Administration ( NARA ). This research, including an assessment of the Charles Davis event, appeared in the publish articles, “ The Flipside of Impressment : british Seamen Taken by the U.S. Navy Prior to the War of 1812, ” The Journal of the War of 1812 10 ( spring 2006 ) : 10–16, and “ Taken on the high Seas : american english Seamen Impressment Records at the National Archives, 1789–1815, ” New England Ancestors 7:4 ( Fall 2006 ) : 17–22.

Read more: A Man Quotes Maritime Law To Avoid Ticket

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government .

Purchase This Issue