Situated in the west coast of the Malay Peninsula on the strait that bears its name, the port of Malacca is adjacent to one of the universe ’ mho busiest embark lanes. today ’ south Malacca ( Melaka in Malay ) is a humble port city with few obvious signs of its former glory. Despite a growing tourist trade, most visitors are ignorant of the city ’ s spectacular maritime past as one of the most crucial trade centers in the early modern ball-shaped economy, a past that put Malacca in the lapp league with Venice, Cairo, and Canton. The average tourist is more likely to mention the city ’ s food than its history. With centuries of deal with China, India, and the arabian earth ; being ruled by the Portuguese, Dutch, and English ; and its close proximity to many of the global ’ mho zest producers, Malaccan culinary polish brings together East Asian, indian Ocean, Halal, and european traditions into a Southeast asian celebration of ball-shaped food. But tasty as they are, these dishes are artifacts of the city ’ s lost bulge. fortunately, city leaders have funded several museums, restoration projects, and archaeological sites to celebrate this malaysian port ’ s function in the populace organization, its active multiculturalism, and significance in maritime asian history .

Despite the port ’ s fantastic importance and wealth in the fifteenth hundred, Malacca ’ s greatness was fleeting. After 1403, a Malay rule quickly transformed it from a sleepy fishing village to a center of global trade in less than a ten, but in 1511, the moral force deal department store fell to Portuguese invaders who gradually ran Malacca into the ground until they were conquered in act by the dutch in 1641. If it became a backwater under colonial rule, a larger diachronic perspective on Southeast Asia shows that there has constantly been a hegemonic port city similar to Malacca in its aura days. Geography, meteorologic patterns, and the logistics of nautical commerce dictated that somewhere along the Straits of Malacca, one city would serve as the regional center in the ball-shaped economic order .

Land, Water, and Wind

french historian Fernand Braudel argued that geography and climate structured the decisions humans could make, placing human agency inside of certain environmental constraints. Although he studied the Mediterranean, his perspective is essential for understanding the history of nautical Asia. A check of the map reveals Malacca ’ s importance. The kingdom literally creates a funnel, as the Malay Peninsula and the island of Sumatra get steadily close as one travels into the strait. Tomé Pires, a portuguese pharmacist, referred to the pass as a “ esophagus, ” and contemporary analysts use the term “ choke point. ” 1

The Straits of Malacca connect the indian Ocean washbasin to the South China Sea. China- oblige nautical deal from India, Persia, and the arabian Peninsula must either pass by Malacca or travel much farther to the confederacy to the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java. While the Sunda passage is allow for ships coming from the Cape of Good Hope, it is a major detour for indian, persian, and arab merchants. furthermore, the winds along the west slide of Sumatra can be unreliable, and the outdoors ocean swells spawned by massive storms in the Southern Ocean provide for excellent surfing in the Mentawai Islands but dangerous sweep for little craft. The equable waters between the northeast slide of Sumatra and the west coast of the Malay Peninsula are well-protected from ocean swells and can seem like a lake when compared to the towering waves of the amerind Ocean .

The monsoon wind instrument cycle adds a final and historically decisive factor to the history of global craft patterns. In the Northern Hemisphere ’ s summer months, a hard-hitting system over .Siberia pulls wet and warm breeze off the indian Ocean, bringing clayey rain and dominant winds that blow toward the northeast. In winter, the form is reversed, with siberian low imperativeness pushing relatively cooler and dry air to the southwest. In the age of sail, it was adjacent to impossible for boats to travel against these winds. Mariners sailed downwind from India or China toward the southern edge of the Straits of Malacca from November to April. From May to October, they used the monsoon winds to push boats north to India or China. This wind form combined with Malacca ’ s geographic localization to make it an ideal rate to await the exchange of the hoist hertz. As merchants going from South Asia to China realized that it was easier and quicker to simply exchange goods with each early at a halfway point in the straits, ports in the region developed into trade emporia where goods from afar could be imported, stored, and exchanged amongst alien merchants. Such a system allowed Indians and Chinese to bring goods from home, exchange them for alien goods, and return home in close to six months, rather than the about two years it would take to travel the full distance .

The Braudelian factors of geography, ocean patterns, and wind cycles made the Straits of Malacca a natural pivot point of commerce in maritime Asia .

Pre-Malaccan Thalassocracies

Before Malacca, there were two big thalassocracies, or sea-going empires : Srivijaya ( eighth through twelfth centuries ) and Majapahit ( 1293–1527 ). initially, the kingdom of Funan ( first through one-seventh centuries ), in what is immediately southern Việt Nam, Cambodia, and Thailand, established maritime barter connections between India and China, with the city of Oc-Eo serve as the independent port. however, with the Straits of Malacca family to respective pirate bands, merchants in the long time of Funan used the overland route at the specialize Isthmus of Kra near the present- day Thai-Malaysian border .

In the seventh hundred, Srivijaya opened up the Straits of Malacca. Using naval office to crush pirates and rivals, the kingdom grew from the region around contemporary Palembang in South Sumatra Province in Indonesia to claim control over most of Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, a lot of Java, and thousands of smaller islands. For centuries, Srivijaya expanded the bulk of deal through the straits as it led military expeditions against potential rivals while ensuring extraneous merchants safe passage and necessary port facilities. After half a millennium of ability, the maritime empire fell to the rising Javanese Majapahit kingdom. Another sea-going empire, Majapahit controlled an evening larger sum of territory at its imperial zenith in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The javanese compound access to the spice islands of the Moluccas with domination of the Straits of Malacca .

These thalassocracies set the exemplar of incredible wealth that would come from servicing the nautical Silk Roads between China and the amerind Ocean basin. Sea-going trade proved itself to be a much more cost-efficient and faster option than Central Asia ’ s thousands of miles of treacherous roads, slowly crossed by camel caravans at a walking pace .

The Rise of Malacca

Following these precedents, the raise of Malacca was simply the newest phase of a centuries-old pattern. While specific details on the establish of the city remain murky and often the thrust of caption, we do know that prior to 1400, Malacca was a little fish village. Malay, Portuguese, and chinese sources hold that the move Malay lord Parameswara ( 1344–1414 ) was in search of a kingdom. Finding a small river that met a beach in the protected waters of strait— all at the metrical foot of a nearby hill that allowed one to observe the coming and going of ships— Parameswara must have realized that the site would make an ideal port that could both serve trade and project military might. consequently, he forged an alliance with the mobile orangutan laut ( known as “ sea people, ” they were literally a floating population of pirates and merchants ) to crush his rivals, scare off other pirates, and encourage merchants into his harbor. If he strongarmed some ships into his port, once there they found authentic trade practices and security in a dangerous area .

Malacca ’ s precisely and uniform trade practices cursorily gained notoriety throughout nautical Asia. Under the insomniac but protective eyes of the cutthroat orangutan laut, merchants who came into Malacca found that the city offered safe and plug warehouse facilities. Ensuring smooth transactions, Parameswara established a system with clear rules on the percentage of incoming cargo that would be taxed. Avoiding opportunities for graft and fiddling corruption, the local government had a hierarchy of officials with four harbormasters, each for an ethnically defined group of merchants such as Gujarati, Bengali, Malay, or East Asian. An executive officeholder stood above them all to arbitrate interethnic disputes and ensure harmonious multicultural department of commerce. Serving as a marketplace for imports to be traded amongst foreigners, the city produced and consumed relatively little .

Within a few years, the successful system made Malacca the most significant trading concentrate in Southeast Asia. With this prosperity, the new city grew. Merchants, laborers, and slaves from throughout Southeast Asia, East Asia, and South Asia soon filled Malacca. Cultural diversity became the norm, and one could hear dozens of languages spoken in the cosmopolitan city ’ s bustling streets .

Tribute State and Sultanate

Parameswara solidified Malacca ’ s position with institutional and personal connections to the great economic engines of his world, China and India. The city ’ s surface coincided with one of the most dynamic phases in chinese history as the early Ming dynasty ( 1364–1644 ) deployed a massive evanesce and established aim relations with the Asia maritime world. The Yongle Emperor ( 1402–1424 ) tasked Zheng He ( 1371– 1433 ) with build and commanding hundreds of ships, some estimated to be over 400 feet in length. not a mission of conquest or exploration, the fleet followed the well-known monsoon trade routes to promote trade and statesmanship by impressing the worldly concern with China ’ south might. nautical powers were encouraged to enter into the Confucian-based tribute-state relationship with the Middle Kingdom. Parameswara himself traveled to the chinese capital to kowtow before the emperor in 1411. In come back for his tribute and respect, the Malaccan rule received honorary robes from the taiwanese court, a symbol of prestige, and, more practically, assurances of taiwanese military aid should it be needed. furthermore, the chinese court granted the city what we might call most-favored-nation condition. If the sinitic tribute department of state arrangement ensured the city ’ s standing to the east, religion solidified Malacca ’ s economic kinship toward the west .

While it is unclear if Parameswara converted to Islam, he adopted titles associated with the religion ( the Persian Iskandar Shah and the Arabic Sultan ) and intermarried with Muslim royal families. This is not storm, as increasing numbers of indian, irani, and Arab merchants began to arrive in Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra and the Straits of Malacca. By midcentury, the city ’ s leadership converted, and a sultan made the Hajj pilgrimage, placing Malacca in the wide Islamic trade network that dominated the greater indian Ocean basin. Muslims from South Asia, Arabia, or North Africa knew that they would be able to find places of worship, individuals conversant with Arabic, and communities governed by companion trade wind practices and influenced by Islamic law codes .

These relationships strengthened Malacca ’ s foreign relations and its domestic vigor. As a tribute express, the city became conversant to Chinese who soon began to reside in the port. muslim merchants from thousands of miles away settled in the city, adding to its ethnic diversity. By the close up of the fifteenth century, Malacca was one of the global ’ s most important cities for trade and home to a cosmopolitan community of over 100,000. Arabs prayed with Chinese. Armenians traded with Javanese. Indians and japanese saw each other in the street .

The Portuguese Crusade

Historians often mark Columbus ’ second 1492 ocean trip across the Atlantic as the dawn of the modern era. This perspective, with its stress on the iberian construction of ball-shaped connections, can obscure the fact that the original goal of spanish expansion was not the unknown New World but rather the markets of East and Southeast Asia. The Portuguese were more immediately successful in this bay. After the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, in which Portugal and Spain agreed to divide the populace into two spheres of expansion, the smaller kingdom sent Vasco district attorney Gama to India to build a deal empire on the far side of the world. unfortunately, the Portuguese had small to sell in Asia and promptly turned to more crimson means of acquiring the spices, silks, and other riches of indian Ocean ports. Alfonso de Albuquerque ( 1453-1515 ), a brilliantly pitiless strategist was the main architect of portuguese asian policy. Recognizing the relative helplessness of his small arm forces on nation, he exploited his fleet ’ sulfur naval transcendence by attacking strategic waterways such as the Strait of Hormuz ( 1507 ) and ports such as Goa ( 1510 ). His ships, bristling with guns and sailors trained in the ways of arm trade in the less-than-peaceful Mediterranean, highjacked Asia ’ s nautical economy. Realizing that control condition of Malacca would give him a near-monopoly of taiwanese goods and spices from the Moluccas, Albuquerque attacked the city in 1511. After several cutthroat battles with the sultan ’ randomness skilled archers and powerful war elephants, the Portuguese conquered the port .

While Albuquerque ’ s aim was to monopolize asian barter by taking this crucial suffocate point, his motivations must be understood in the context of early advanced Europe. Coming out of the Crusades and feudalism, Islamophobia and the warrior culture were central to the Portuguese worldview. But this conquistador besides understood global patterns of trade and realized that if he seized Malacca, Portugal would gain an upper hand on a european commercial rival : the city of Venice. Since the Venetians made frightful profits selling easterly goods to the Iberians and as the merchant republic got along a little excessively well with their Muslim colleagues, a move in Southeast Asia would solve a Mediterranean political crisis. Albuquerque justified his assault on the larboard in a speech to his men :

And I hold it as identical certain that if we take this trade of Malacca aside of their hands, Cairo and Méca are wholly ruined, and to Venice will no spiceries be conveyed except that which her merchants go and buy in Portugal.2

clearly, the commander saw the universe as a sophisticate trade system but besides as a acerb clang of civilizations between Islam and Christianity. The merchants of Venice immediately understood the menace to their centuries-old trade with the East, which indeed went into an immediate and irreversible decline. The catholic invaders viewed Southeast asian Muslims with the lapp hostility and contempt displayed in Iberia, killing or expelling them from the city. Mosques were torn depressed and churches raised in their plaza. The subsequent century saw about constant war between Portuguese Malacca and the neighbor Sultanates of Johore and Aceh. When compared with the spanish Americas and Philippines, portuguese missionary natural process was spectacularly abortive in Asia, and ironically, anti-Muslim policies may have sped up conversions to Islam as a mean of resisting the iberian invaders. Visiting priests, such as the Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier, disparaged the city ’ s lack of piety and reputation for sin.

Read more: Maritime search and rescue – Documentary

After a century of emergence, Malacca went into a time period of demographic instability. As many cultural Malay Muslims and orang laut fled with the sultan and only a handful of heathen Portuguese arrived in the city, the new rulers encouraged the migration of mixed-race Catholic converts from India. Others made it to Malacca from Portuguese colonies in Brazil, Africa, East Timor, and Macau. While Catholics remained a minority, the city ’ s Hindu and Buddhist communities grew as indian and chinese merchants took up residence. As earlier, the new arrivals brought newly food and increased the city ’ s cultural diversity .

Under the 130 years of portuguese rule, trade declined. Muslim merchants found equal ports, and Protestant Europeans soon posed a serious terror. Increasingly, Portuguese Malacca survived only as a military frontier settlement in a sea of enemies .

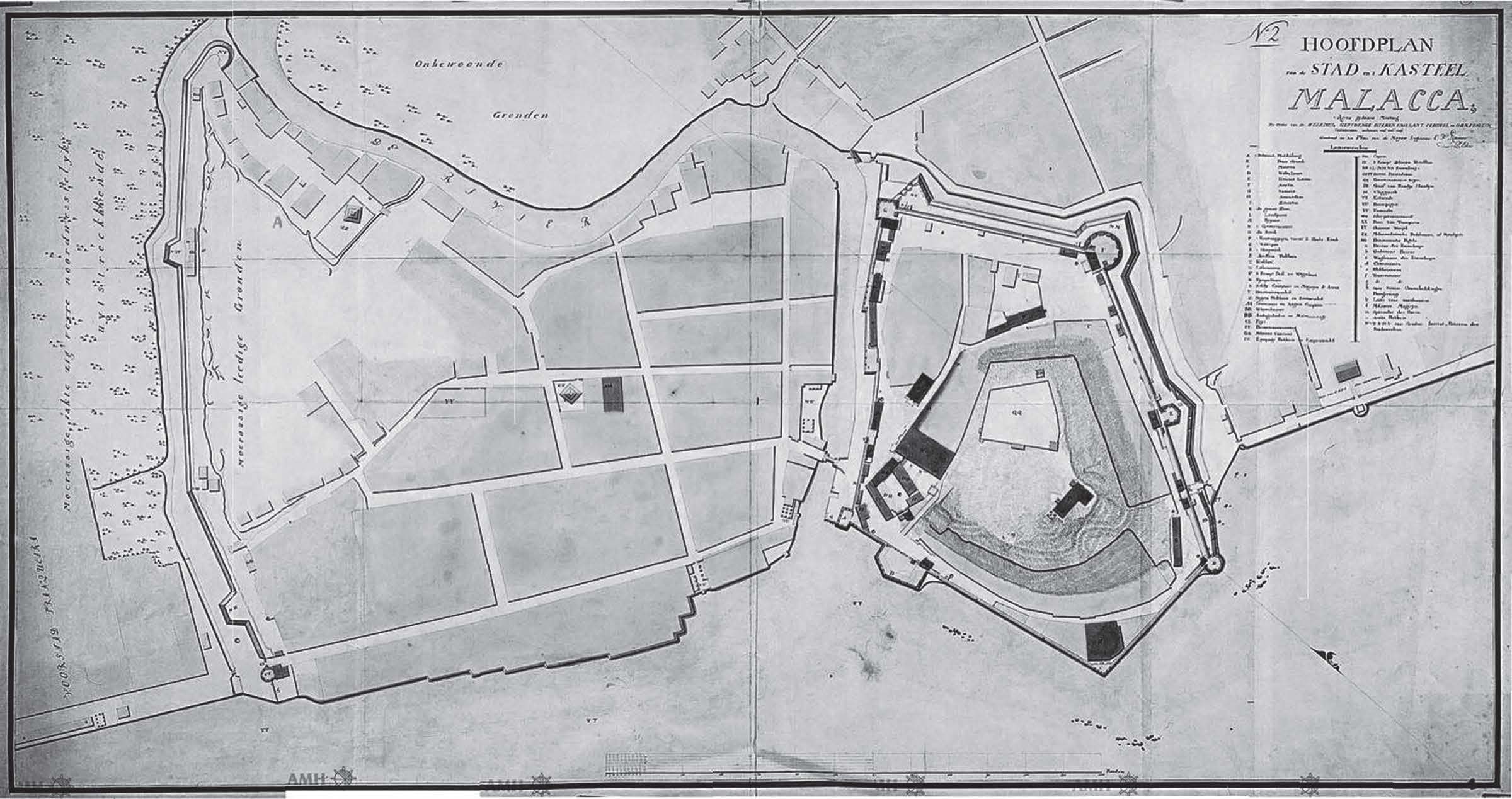

Stagnation and Displacement under the Dutch and British

When the Dutch arrived in Southeast Asia, they brought a new shape of economic organization : the mod corporation. After its creation in 1602, the Dutch East India Company ( VOC ), with its system of buying and selling shares in the company, diversified gamble for its many investors after its universe in 1602. The iberian feudal elites and their merchant allies could not compete with the forces of early on modern capitalism. The VOC ’ sulfur Batavia, contemporary Jakarta, quickly took over the spiciness craft, redirecting commerce away from the Straits of Malacca and toward the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra. When the Dutch replaced the Portuguese as masters of the city in 1641, the new Protestant rulers held the port only to keep it out of the hands of their rivals. The few dutch who immigrated to Malacca did build classifiable buildings for VOC officials and merchants .

In the early nineteenth century, the british East India Company took an sake in the Straits of Malacca. english ships loaded with opium from India passed through Southeast Asia on their way to Canton. In order to secure this crucial waterway, the british negotiated control of Malacca by the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty. however, Thomas Stamford Raffles ( 1781–1826 ) established Singapore as the center of english operations in the region and Malacca remained a backwater. When the naturalist Russel Alfred Wallace ( 1823–1913 ) visited in the 1850s, he wrote the follow :

The population of Malacca consists of several races. The omnipresent Chinese are possibly the most numerous, keeping up their manners, customs, and linguistic process ; the autochthonal Malays are future in point of numbers, and their language is the lingua-franca of the rate. following come the descendants of the Portuguese—a assorted, degraded, and debauched race, but who even keep up the use of their mother tongue, though ruefully mutilated in grammar ; and then there are the english rulers, and the descendants of the Dutch, who all speak English.3

While neglected by the authorities, the port ’ sulfur vibrant multiculturalism continued to flourish. Under british dominion, the chinese population grew as separate of the larger Peranakan Chinese community. As with the Portuguese and Dutch, many taiwanese men took Malay, Javanese, and Balinese brides and concubines, producing a hybrid culture. Malacca ’ s Baba-Nyonya cuisine combines southern taiwanese dishes with spices and cooking techniques of Southeast Asia .

Contemporary Malacca

A phone number of factors combined to marginalize the once-great port city. In the twentieth hundred, Malacca ’ s harbor served regional ships picking up canister and rubberize from nearby mines and plantations. Yet this department of commerce was fairly minor, and the city became a backwater, eclipsed by Singapore to the south and Georgetown to the north. The british choose landlocked Kuala Lumpur as the political center of the colonial Federated Malay States. While the nationalist drawing card Tunku Abdul Rahman ( 1903–1990 ) did famously utter “ Merdeka ” ( “ exemption ” ) in Malacca in 1956 and drew upon the city ’ s historic bequest in his speeches, the follow year he declared independence in Kuala Lumpur. With rising Malay nationalism, Malacca ’ s diverseness raised some eyebrows in regards to the city ’ s authenticity .

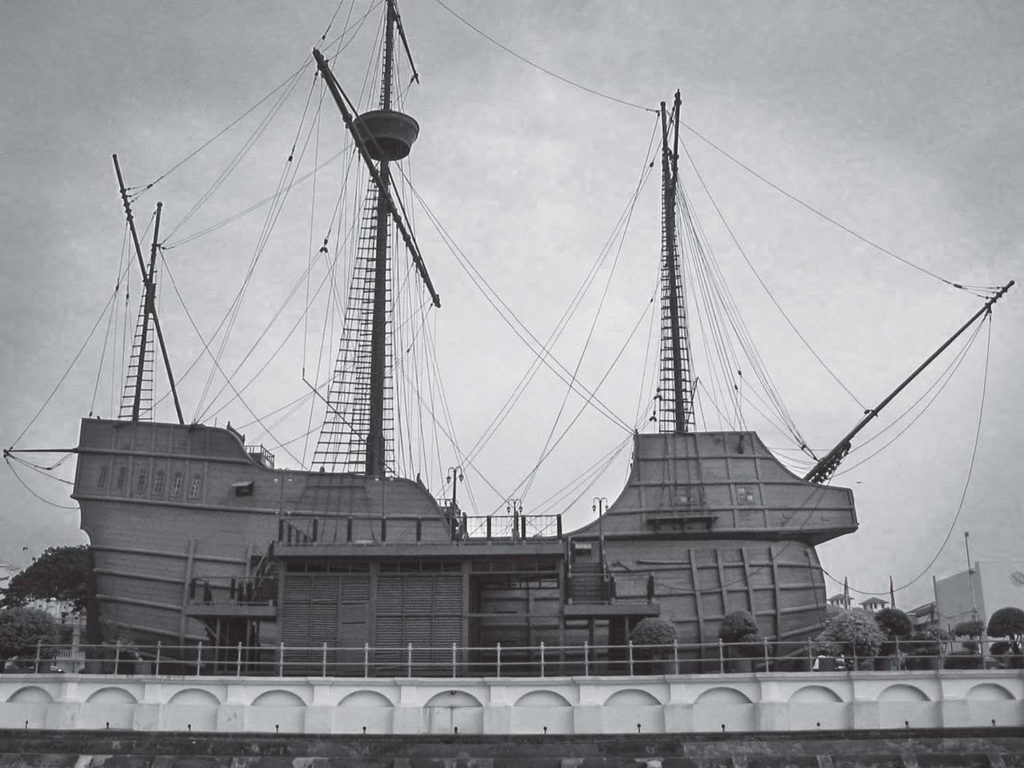

however, a new wind is blowing into Malacca. In recognition of its significant function in nautical history and divers culture, the city became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008. Tourists can see the colonial past in ruins of the Portuguese A Famosa Fort ( 1511 ) or the dutch Stadthuys ( 1650 ). The hungry can sample local anesthetic specialties in Baba Nyonya restaurants on Jonker Street. A number of museums represent the port ’ s past as a center of Malay culture but besides the touch place of the Chinese and Islamic worlds, best seen in the exhibits and statues that celebrate Zheng He. For today ’ randomness visitor, history in Malacca is alive and well .

Share this:

- More

MICHAEL G. VANN is Associate Professor of History and asian Studies at Sacramento State University and specializes in colonial Southeast Asia. In 2013–2014, he was a Fulbright Senior Scholar at the Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, and a aged Fellow at the Center for Khmer Studies in Siem Reap, Cambodia. He is a by President of the french Colonial Historical Society and his publications include studies of cartoons in Saigon, informer hunting in Hanoi, and a javanese haunted house. Vann ’ s film Cambodia ’ s other Lost City : french Colonial Phnom Penh may be viewed on YouTube .