U.S. Route 1, the nation ’ mho longest north-south highway, casts out of Fort Kent, Maine, and spools down the easterly seaside, threading Boston, New York, and Fort Lauderdale until it drifts across Manatee Creek near Homestead and bobs south into the Florida Keys, which carry it indeed far west that it snags on a longitude line shared with Cleveland. The 2,369-mile route ends on Whitehead Street in Key West. here, a six-hour water-ski from Havana, a sign announces that you have reached the goal of the rainbow and end of the route. The motto sums up pretty fairly the two reasons people have been drawn to Key West over the decades. Either they came looking for gold — literally, in some cases, thanks to the shipwrecks produced by the local reef — or they came for the freedom of apparitional demarcations, the sort you find in a seat where people stop running only because they ’ ve run out of road .

When Jay Miscovich came to Key West in 2009, he had treasure in mind. Miscovich was a fifty-year-old, 300-pound real-estate investor from Pennsylvania who had recently lost everything in the fiscal crash and was relying on his mother ’ s Social Security check to get by. He did not find aureate, but as he would explain to a federal evaluate at a judiciary trial in December 2012, a match of blocks from the terminus australis of U.S. 1, he soon came into self-control of more than a hundred pounds of roughly colombian emeralds. He ’ five hundred discovered them, he testified, while aqualung dive in international waters forty miles north of the island .

The discovery seemed at beginning to be unambiguously dependable news program, and however less than a year after Miscovich ’ sulfur testimony, patrol would find him dead of a self-inflicted shotgun wound. “ I ’ ve loved many beautiful women, built my business and found an amazing treasure, ” he said in a note he left for his friends and family. “ sol preceptor ’ triiodothyronine mourn my death, celebrate my life ! ”

Reading: Emerald Sea, by Robert P. Baird

Miscovich ’ s appearance at the bench trial was neither his first nor his last try to establish his claim to the emeralds, but it did represent his fullest populace report of their discovery. To hear him tell it, the report started as every prize hunt should : in a bar, with a beer, over a map and a part of coral-encrusted clay. In January 2010, Miscovich said, a handyman who had done work for him in Pennsylvania, a guy named Mike Cunningham, had arranged a meeting at the Bull & Whistle, a tourist bar in Key West. Cunningham bought his erstwhile bos a beer, produced from his pocket a triangulum of break pottery, and explained that he ’ five hundred found the potsherd while aqualung dive. He showed Miscovich a photocopy of a nautical chart. An ten marked the placement of the receive .

At the meter of the meet, Miscovich had recently devoted himself full-time to what some people in the commercial enterprise, straining the bounds of professional modesty, call marine salvage. Right away, he recognized a classifiable polish on Cunningham ’ s artifact. “ I knew from the pink glaze that it was decidedly spanish colonial-era pottery, ” he testified late. “ King Philip had a patent on it. He shipped it all over the world. ” Colonial-era pottery, of course, was carried on colonial-era ships, and there wasn ’ triiodothyronine a prize salvager in Florida, professional or otherwise, who could hear the give voice “ colonial-era transport ” without thinking immediately of the flota de Tierra Firme, a fleet of armed galleons that set out every class or so to carry the riches of the New World back to Spain .

Miscovich said that this was the break he ’ d been hoping for. The son of an elementary-school teacher and a steel-mill worker, he grew up collecting rare coins and baseball cards in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, the little town near Pittsburgh made celebrated by Rolling Rock beer. Though he held an M.D. from a Caribbean medical school, he ’ five hundred made a life for himself as a serial entrepreneur. He had owned a trio of nurse homes and later spent the go-go years of the millennial housing boom flipping properties in and around Latrobe. But by 2009 he was more than half a million dollars in debt, therefore broke that he was forced to sell his dishwasher, stove, and refrigerator to pay the bills .

Miscovich had been fascinated by gem hunting since the 1980s, when he heard stories about diving expeditions from a charwoman in his local aqualung club. In the decade before the mortgage crisis wiped him out, he invested in half a twelve treasure outfits, including one of several companies founded by Mel Fisher, who discovered the Tierra Firme evanesce ’ s most lucrative bust up, the Nuestra Señora de Atocha. According to Miscovich, however, none of his investments had paid off in anything more than trinkets. “ I started realizing that [ for ] most of these treasure-hunting companies, the very prize was making money by taking it from their investors, ” he told the court. “ I decided to do it on my own, and decided I could do it better. ”

In 2009, Miscovich borrowed money from friends and family for his new guess. He formed a partnership with Stephen Elchlepp, a professional diver who ’ d been running the Key West position of one of the care for companies in which Miscovich had invested, a private tauten that was about to merge with a small publicly traded company called Oceanic Research and Recovery ( ORRV ). Whereas Miscovich was a diabetic who slept with a CPAP car, and was so fleshy that he had to tape up his eyelids to keep the skin from drooping, Elchlepp was built like a bullet, and trained like one besides. A former Navy weapons technician who had served on an aircraft carrier, he ’ five hundred learned to scuba dive when he was six years previous. The two men hit it off right aside .

“ We talked about how neat it would be to be involved in a company that would be established and looked up to, ” Elchlepp told the New Times Broward–Palm Beach in 2013. He and Miscovich, he said, “ were so tired of hearing the professional communities bashing care for hunters because they ’ rhenium known as smash-and-grab guys. We wanted to change that. ” The men collected a drawer ’ s worth of leads and promising GPS coordinates, and they spent the fall of 2009 hunting for sink gem. “ We dove on dozens and dozens of wrecks, ” Miscovich told the court in 2012. “ Whenever the weather was permitting, we were come out of the closet. ”

The glaze pottery that Cunningham showed Miscovich at the Bull & Whistle set his kernel race. “ normally, when you get leads to potential wreck locations, you don ’ thymine get anything with them, just locations, ” Miscovich testified. “ Because of the fact that we actually had a solid artifact in our bridge player I was more stimulate than usual. ” Despite his fiscal straits, he immediately bought the map and the shard for $ 500 .

The adjacent day, Miscovich said, the partners set out in Elchlepp ’ s twenty-five-foot Grady-White and followed the chart into external waters. When they approached the descry marked by the ten, they lowered a magnetometer into their wake and towed a rigorous traffic pattern, a practice known as mowing the lawn. Whenever the magnetometer spiked, the men dropped a homemade buoy — a spray-painted body of water bottle — as a marker. After a handful of buoys were in the water, Elchlepp went down to investigate, while Miscovich, whose fleshiness and asthma made rapid descents unmanageable, manned the boat .

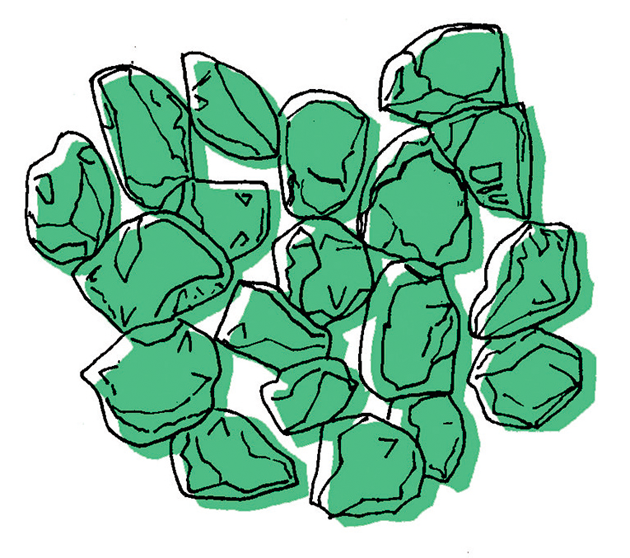

On their first gear two days out, the partners found fiddling but pipes and bit metallic. On the third base day, while exploring an area about a mile and a one-half from the adam on Cunningham ’ sulfur function, they dropped three buoys in close proximity. Miscovich decided to dive. He put on his aqualung gear and followed Elchlepp down sixty-five feet to the ocean floor. The visibility subaqueous was limited, but when Miscovich reached the area under the third base buoy, he saw a seize of empty Budweiser cans — the campaign, he suspected, of the magnetometer ’ sulfur spike. Fifteen feet away, he saw something else. “ I thought it was break looking glass, ” he testified. “ It was kind of glistening on the bottom. Colors are reasonably hard to detect at distances. When I got close to it, within a few feet, I could decidedly discern a lot of green all over the buttocks. ”

A gallant son of Latrobe could be forgiven for having fleeceable bottles on the brain, but after Miscovich picked up a handful of the break up pieces he realized that he wasn ’ t holding looking glass. “ I was rolling it around in my hands, and I ’ thousand looking and looking at it and examining it, and I ’ thousand think, No, it couldn ’ metric ton be. ” Miscovich signaled to Elchlepp that he wanted to ascend. Back on the boat, he dropped the green pieces on the hat of a white plastic cooler. “ I just kind of threw them and said, ‘ Look at this. I think these are emeralds. ’ ”

A gallant son of Latrobe could be forgiven for having fleeceable bottles on the brain, but after Miscovich picked up a handful of the break up pieces he realized that he wasn ’ t holding looking glass. “ I was rolling it around in my hands, and I ’ thousand looking and looking at it and examining it, and I ’ thousand think, No, it couldn ’ metric ton be. ” Miscovich signaled to Elchlepp that he wanted to ascend. Back on the boat, he dropped the green pieces on the hat of a white plastic cooler. “ I just kind of threw them and said, ‘ Look at this. I think these are emeralds. ’ ”

ecstatic, Miscovich and Elchlepp grabbed some ziplock bags and headed back subaqueous. “ We went square over to where all the emeralds were on the bottom, and we immediately started picking them up, ” Miscovich told the court. “ There was so many of them it was like picking cherries on a cerise tree. ”

two. emerald reef

Jay Miscovich ’ s relationship with his younger brother, Scott, had been strained for much of their pornographic lives, but in March 2010, two months after his discovery, Jay called to relay the news. Like his brother, Scott held a checkup degree from the American University of the Caribbean. Unlike Jay, Scott besides held an undergraduate diploma from Cornell, and had gone on to do a residency at Yale. A member of the ethics committee of his local hospital, he had worked as a family-practice doctor in Kailua, Hawaii, for more than two decades. Scott told me recently that Jay was “ wholly obsessed and passionate ” about finding a shipwreck. Whenever the brothers spoke on the earphone, he said, Jay would “ talk about his houses, then he ’ d flip it to treasure. ”

According to Scott, Jay worked intemperate at everything he did. But he besides had an hotheaded streak. “ He would be one of those guys that would go in and equitable buy a house on the spot from the bank. That was fair the means he operated. ” Though Jay ’ s real-estate dealings had made him a paper millionaire for a time, affluent enough to own a 5,200-square-foot hilltop sign of the zodiac, Scott worried that his brother did not have the business grok to manage a unplayful recover. indeed, it was possible to see Jay ’ s exuberance for gem hunt, his taste for the farseeing tear, as validation that he was not ideally equipped to handle an honest-to-god treasure hoard. By the time he called Scott, Jay had already raised around $ 80,000 from the CEO of ORRV — Elchlepp ’ s previous employer — and one of the company ’ randomness chief investors. Jay had besides commissioned a ally, a Pennsylvania jeweler named Michael Vesely, to set some of the emeralds in amber. But after Jay said that he wanted to sell the emeralds while touring the country in a lease motor home, Scott warned him, “ You ’ re going to end up dead in a trench if you think you ’ re going to tote around fifty to sixty pounds of emeralds. You don ’ t barely get in a Winnebago and start driving about. ”

Jay ’ s plans worry Scott enough that he called Dean Barr, a hedge-fund director who had been his brotherhood brother at Cornell in the early 1980s. He told Barr about the discovery, and said that Jay needed aid : serve setting up a business to support the salvage operation, assistant market the emeralds, and help recruiting investors he could trust. “ I was reaching out for guidance, ” Scott explained to the court at the 2012 judiciary trial, “ because, being from a small township in Pennsylvania, he didn ’ t have that type of skill. ” Barr, who held an M.B.A. from NYU, was another history : in 2005, at forty-five, he had been hired to run Citigroup ’ s $ 40 billion alternative-investment whole. After he was replaced by Vikram Pandit, Citigroup ’ s future CEO, Barr started his own billion-dollar private-equity firm in Greenwich, Connecticut .

In court testimony, Barr described himself as initially disbelieving of Jay ’ s fib. Nevertheless, after Scott sent along photograph of the emeralds, Barr invited Jay to meet him in New York. In early April 2010, at the Manhattan position of Proskauer Rose, the law tauten that represented Barr, Jay unzipped a green duffel bag bag and covered the glossy surface of a conference postpone with gallon-size ziplocks broad of emeralds, amethysts, and quartz glass crystals. There were several hundred stones, Barr would recall late. Most of the emeralds were little, but some of the specimens composed of emerald and quartz glass were a boastfully as a fist and weighed closely half a beat. As curious lawyers eyed the gems, Jay told Barr about the map, though he did not mention Cunningham by mention .

The two men returned to Proskauer a week later to meet the head gemologist of Christie ’ south, who confirmed that the stones were actual emeralds. many were not gem quality, she told them, but she besides said that validation the emeralds had come from a shipwreck could multiply their value ampere much as eight times. Barr decided to invest. On April 19, he paid Proskauer a $ 50,000 servant to create Emerald Reef LLC, a company whose determination was to organize the recovery of more emeralds and to locate the shipwreck from which they came .

The two men returned to Proskauer a week later to meet the head gemologist of Christie ’ south, who confirmed that the stones were actual emeralds. many were not gem quality, she told them, but she besides said that validation the emeralds had come from a shipwreck could multiply their value ampere much as eight times. Barr decided to invest. On April 19, he paid Proskauer a $ 50,000 servant to create Emerald Reef LLC, a company whose determination was to organize the recovery of more emeralds and to locate the shipwreck from which they came .

not long after, Barr ’ s personal accountant, Neil Ash, besides agreed to invest in Emerald Reef. ( Both declined to comment for this floor. ) Barr and Ash, who became known as the New York investors, brought in a handful of others to back Emerald Reef, but the two men would end up contributing the lion ’ s parcel of its working capital. They cursorily took agitate of setting the company on a proper foot. They drew up capitalization tables for a series of limited-liability corporations and financed the purchase of a $ 700,000 115-foot dinner-cruise gravy boat called the Spirit of La Salle. Scott spoke to experts in marine archeology, and Elchlepp, the most have treasure hunter in the group, was tasked with hiring divers, transforming the Spirit of La Salle into a proper salvage ship, and arranging expeditions to the site, which was yielding, by Jay ’ mho estimate, some 10 to 20 million dollars ’ worth of emeralds per trip .

By the end of that summer, the emerald hoard, which Elchlepp was storing in Key West, in a accelerator safe at his sign of the zodiac, weighed more than eighty pounds. At Jay ’ s urge, the group commissioned an Oxford-trained marine archeologist to produce a composition about the find to circulate to potential investors. Jay was intelligibly eager to keep the coordinates of the emerald site a mysterious, and he was careful to tell the archeologist a fib that was reasonably different from the one he ’ d told his partners — it placed the detect in early 2009, for exemplify, and made no note of a treasure map. The archeologist ’ second report noted that the emeralds were associated with no known shipwreck, and it concluded with a excusable morsel of hyperbole : “ Dr. Jay was in a unique position ; he had discovered treasure before the treasure hunt had even begun ! ”

Though Emerald Reef had attracted more than $ 6 million in investment commitments, for a lot of that summer Jay remained, in what would become a darling idiom, “ emerald full-bodied and cash poor. ” Barr and Ash had agreed to send him $ 10,000 each workweek, money that was meant to fund the company ’ south salvage operations and to pay down his personal debts, which, they feared, could cause P.R. problems when the witness became public. But not even the hebdomadally stipend kept Jay more than half a footprint ahead of his creditors. He told Ash that he was closely dispossessed — “ my 14 year old car burns 2 qts of vegetable oil a workweek, ” he wrote in an e-mail — and that his debit card had been rejected when he tried to buy lunch for his dive crew in Key West. “ I understand I and the house doss created all my problems, and you and Dean are trying to help, ” he wrote. inactive, he complained, bringing the emeralds to market was “ taking so long. ”

Jay blamed much of the stay on the lawyers, but as the attorneys at Proskauer were learning, claiming ownership of sink gem was in some ways more unmanageable than finding it. U.S. admiralty law stipulates that the rights to sunken cargo can persist many centuries after a wreck, and the spanish politics in particular has been ruthless in pursuing prize lost during the point years of its transatlantic conglomerate. For this argue, Emerald Reef ’ randomness lawyers had begun to consider a scheme to make an admiralty claim in a foreign state — the Cayman Islands, say — whose laws would make it more difficult for Spain to secure ownership. Proskauer advised Jay and his partners not to sell any of the emeralds until their legal rights were ensured .

The value of the emeralds presented another complication. At times, Jay suggested that the hoard could be deserving angstrom a lot as half a billion dollars, but the shares he sold Barr and Ash implied a more meek evaluation of $ 10 million. To help resolve the doubt, Jay, Barr, Vesely, and others traveled to Washington, D.C., in August to meet Jeffrey Post, the forefront curator of the Smithsonian ’ s gem collection. According to Post, who is by many accounts the nation ’ s top gemologist, Jay brought his duffel bag into a league room in the National Museum of Natural History and “ started pulling credit card bags full of emerald crystals out. ” Post told me recently that there were so many emeralds on the table that he called a colleague in to help examine them. “ There were thousands, ” he said. “ never in my life have I had that many emeralds piled up on a postpone in front of me. ”

Like the gemologist from Christie ’ randomness, Post said that the emeralds were not well suited for jewelry. still, the visible bearing of pyrite — fritter ’ second gold — in the stone matrices, along with the emeralds ’ form, color, and measure, strongly suggested that they were from Colombia. “ There aren ’ t a set of places that, historically or evening now, could produce that number of emerald crystals in one invest, ” he explained to me. According to Vesely, Post said that some of the stones looked like they were from Muzo, a region north of Bogotá from which the populace ’ s most valuable emeralds originate. The group was thrilled : there was talk of permanent donations and joint exhibitions with the Hope ball field. Before Jay left the position, he promised to send Post a handful of emeralds directly from the dive web site to examine under a scan electron microscope. That good afternoon, Dean Barr emailed a likely investor : “ It was a home run ! Jeff Post ? said, and I quote, ‘ This has been a once in a life experience for me. ’ This ridicule has seen everything. ”

It ’ s a kind of green that rips your center out, ” a jeweler in Florida told me, speak of the blue tad of green that distinguishes Muzo emeralds from those found in Madagascar, Zambia, and even other regions of Colombia. Emeralds are far scarcer in the earth ’ mho crust than diamonds, and the stones that come from Muzo owe their cardiectomic hue to unusually high concentrations of chromium. “ That particular shade of green is region of the legend of the Muzo people in the creation of the global, ” the jeweler said. According to the Muzo Indians, whose discussion by colonial Spaniards athirst for gemstones would seem to justify the theory, emeralds were a arrant precipitate of sorrow : the tears, they believed, of Fura, the earth ’ south first woman, who was left alone and inconsolable after her conserve killed her fan and then stabbed himself. The spanish, for their separate, speculated that Muzo ’ south emeralds got their color through a process of solar ripen .

colombian emeralds are now recognized as the finest in the global, but this was not always the case. Once the Tierra Firme fleet could be counted on to supply the Old World with an annual flood tide of emeralds, traders in Seville, Lisbon, and Goa began to divide stones into two categories : Oriental and Western. Just as jewelers today can sell emeralds with a shipwreck birthplace for many times the price of those that lack a romantic backstory, so, besides, did the lapidaries of Europe and South Asia put a higher price on stones that were believed to have come from ancient egyptian mines. As Kris Lane notes in Colour of Paradise, his history of the emerald trade, Oriental emeralds frequently sold for doubly equally much as their western counterparts. This differentiation persisted throughout the early advanced period, though recent test has revealed that most of the alleged old emeralds were no older than the new : closely all of the gems believed to be egyptian were in fact from Colombia .

colombian emeralds are now recognized as the finest in the global, but this was not always the case. Once the Tierra Firme fleet could be counted on to supply the Old World with an annual flood tide of emeralds, traders in Seville, Lisbon, and Goa began to divide stones into two categories : Oriental and Western. Just as jewelers today can sell emeralds with a shipwreck birthplace for many times the price of those that lack a romantic backstory, so, besides, did the lapidaries of Europe and South Asia put a higher price on stones that were believed to have come from ancient egyptian mines. As Kris Lane notes in Colour of Paradise, his history of the emerald trade, Oriental emeralds frequently sold for doubly equally much as their western counterparts. This differentiation persisted throughout the early advanced period, though recent test has revealed that most of the alleged old emeralds were no older than the new : closely all of the gems believed to be egyptian were in fact from Colombia .

On September 10, 2010, Jay and several early members of Emerald Reef met at the New York office of FleishmanHillard, a public-relations firm. The sample that Jay sent Jeffrey Post, complete with sand, shells, and plant life, had revealed something noteworthy. In an e-mail that Barr read out brassy at FleishmanHillard, Post said he ’ five hundred found bantam grains of gold embedded in the crevices of the emeralds. “ Ocean sediments typically do not contain aureate grains, ” Post wrote. “ Their presence seems consistent with the estimate that these emeralds were on the seafloor associated with gold objects for some period of time. ” He speculated that there might have been “ gold coins or other objects that have been slightly abraded by being rolled around in the sandpaper and sediments. ”

Scott Miscovich told me that he and the others were “ flabbergasted ” by the electronic mail. “ Everybody thought that they were sitting on the verge of history. It was electric. ” The amber particles that Post had discovered suggested the emeralds ’ shipwreck birthplace, but they besides hinted that an even more valuable bounty was waiting to be found. “ When you talk about the spanish and what was happening back then, the emeralds were the english cargo, ” Scott said. “ The large cargo was the gold. These things had then much gold on them that your head spins. ”

Despite the excitation, the meeting at FleishmanHillard would in fact mark the begin of the end of Emerald Reef as a company. When Scott arrived, a few minutes late than the others, he placed respective bags of emeralds on the table. The batch surprised Barr and Ash, because Jay had previously agreed to transfer the entire collection to a safe-deposit box in New York. Scott explained that Jay had sent him the emeralds months early, as an temptation to show electric potential investors in Hawaii, but Ash was wary. At that here and now, he wrote late, in a legal filing, he began “ to suspect that Jay Miscovich was not dealing honestly with the Investors and Emerald Reef, LLC. ”

The distrust, it turned out, was reciprocal. Though every agreement that Jay had made with his investors had guaranteed him a majority interest in Emerald Reef, he and Scott were increasingly concerned that the New York investors were trying to wrest control of the treasure. Jay became specially unnerved when the lawyers at Proskauer sent him a draft of a will that would make Barr and Ash the executors of his estate of the realm in the consequence of his death. A few days after the meeting at FleishmanHillard, Jay had to remind Ash that he still owned the gems. “ If I want to keep emeralds in PA, ” he wrote in an electronic mail, “ I will. ”

On his way out of the meeting, Jay told the group that he was going to visit Emerald Reef ’ s safe-deposit box, at a Citibank on Park Avenue, to store the emeralds that Scott had brought from Hawaii. But when Ash went to the bank a few days subsequently with two potential investors, he discovered that Jay had removed many of the emeralds, including some of those believed to be the most valuable. Barr and Ash complained that the lacking stones had caused the investors, who were prepared to contribute $ 1.8 million, to walk away. Jay wrote back, “ I don ’ metric ton give a sleep together about their money. ”

In mid-September, in an undertake to keep the company together, the two sides agreed in principle to a new structure for Emerald Reef. Under the terms of the agreement, Jay would retain his majority equity impale, while his vote rights would be set at 25 percentage. Barr and Ash paid Jay $ 180,000 to sign the agreement, but whether the term tabloid was legally binding remained in challenge. By October, the operations of the ship’s company had ground to a crippled, and each side was convinced that the other was trying to steal the emeralds. After Barr and Ash learned from an Emerald Reef employee that there were distillery boxes of emeralds in Elchlepp ’ mho house, their lawyers hired a private investigation firm staffed by former Navy SEALs to monitor Jay in Latrobe and Elchlepp in Key West. When Elchlepp realized that the P.I. ’ south were casing his sign of the zodiac, he attempted to move the emeralds, in the middle of the night, to another island in the Keys. One person I spoke to recalled that officers from the Monroe County Sheriff ’ s Department offered Elchlepp an escort and threatened to arrest the P.I. ’ s if they didn ’ thyroxine stop harassing him. ( The sheriff ’ mho department has no record of the incident. )

meanwhile, Ash persuaded officials at Citibank to change the lock of the safe-deposit box. Jay was ferocious when he found out, and he became even angrier after he got son that the investors were contemplating legal action. In mid-december he warned that he would press charges for attempted larceny if the lawsuit went advancing. Despite this terror, in January 2012 Barr, Ash, and a third gear investor sued Jay — first in Florida, then in Delaware — for control of Emerald Reef .

For Scott, the actions of the New York investors were confirmation of a atrocious fear : the sophisticate financiers whom he had brought on board to help his brother were nowadays attempting to usurp the determine. From the documents that Barr and Ash had asked him to sign, he told me, “ it truly looked like the entire restraint of the organization shifted over to Dean and Neil completely. ” Scott acknowledged that Jay was not the easiest person to get along with : “ He was endearing, he could make you laugh, and so far he had an aggressive, angry side. I flush started to wonder if he had some signs of rapid-cycling bipolar. ” Nevertheless, Scott was not about to sit by if Jay got swindled .

back in September, when the latent hostility with the investors had begun to mount, Scott had sought advice from Paul Sullivan, his neighbor and best supporter. Sullivan was a semiretired real-estate developer who in decades by had been a political heavyweight : a early executive conductor of the democratic National Committee, a campaign adviser to Walter Mondale, and a deputy campaign coach for Bill Clinton in 1992. In holocene years, Sullivan has rented several hawaiian properties to Barack Obama for the president ’ s annual winter vacations .

Sullivan had scoffed when he first heard Jay ’ s fib, earlier that year. But after Scott showed him some of the emeralds, Sullivan began to advise the Miscoviches in their dispute with the New York investors. Sullivan declined to comment for this floor because of ongoing litigation, but according to Scott, “ Paul was involved in this because he thought that person was trying to take this poor local guy ’ s treasure. He ’ sulfur like, ‘ These people are trying to steal this prize ! This is wrong ! ’ ”

Sullivan had scoffed when he first heard Jay ’ s fib, earlier that year. But after Scott showed him some of the emeralds, Sullivan began to advise the Miscoviches in their dispute with the New York investors. Sullivan declined to comment for this floor because of ongoing litigation, but according to Scott, “ Paul was involved in this because he thought that person was trying to take this poor local guy ’ s treasure. He ’ sulfur like, ‘ These people are trying to steal this prize ! This is wrong ! ’ ”

Sullivan besides offered to help the Miscoviches in their admiralty negotiations with foreign governments, which could be, he would testify late, “ extremely sensible and confidential. ” With Scott by his side, Sullivan reviewed emails, term sheets, and other proposals — including the gulp of a bodied filing to be made in the Cayman Islands. In early December 2010, he and Scott arranged an appraisal of the emeralds, which now numbered more than 50,000. The appraiser estimated that some of the individual stones, as gems, were deserving more than $ 21,000 ; once a shipwreck birthplace was factored in, the sum value of the emeralds, by Sullivan ’ sulfur calculations, was in the hundreds of millions of dollars .

Armed with this information, Sullivan flew to Colombia just ahead Christmas and spoke to respective elder government officials about the possibility of filing an admiralty claim there. Emeralds had constantly been a bloody business in Colombia : well into the twentieth hundred, miners worked their trade with eight-foot iron rods, and could be shot on view for stooping to pick something up off the ground. But even the fleeceable Wars of the 1980s, which left more than 6,000 dead, were no pit for the brutal conditions under which slaves and Indians worked to satisfy the colonial fiebre verde. Scott told me that his historical inquiry had given him the idea that Spain ’ randomness lawyers might be held off by the moral charge of a colombian call : “ I ’ thousand looking at this and saying, ‘ Well, it doesn ’ t belong to any of you. It belongs to those people in those small villages in Colombia whose relatives died for this. ’ ” Jay, for his separate, was will to give Colombia 70 percentage of the discover, reserving 30 percentage for Emerald Reef as a salvage prize. Scott told me that his brother never wanted more than a couple of million dollars. “ His sake was just to get enough money to have a evanesce of ships to look for more treasure. ”

With Sullivan ’ s aid, Jay found a lawyer to defend himself against the New York investors, a big corporate lawyer in Delaware named Bruce Silverstein. After calling Jeffrey Post at the Smithsonian, meeting the appraiser whom Scott and Sullivan had hired, and negotiating the tip for his firm — 5 percentage of the entire value of the determine — Silverstein took the shell. Before retentive, he persuaded his opponents to submit to mediation. By late March 2011, the two sides agreed that the New York investors would receive a $ 5 million promissory notice in rally for relinquishing their claims on the emeralds, dropping their lawsuit, and releasing Jay and other members of Emerald Reef from future liability .

Though hints of the emerald find had appeared on obscure Internet forums, for the most character Jay and his partners had kept the discovery a clandestine. But on a cold and cloudy day, in February 2011, Jay opened the door of his family in Latrobe to find a CBS News crowd on his stoop. With the cameras rolling, Armen Keteyian, CBS ’ randomness chief fact-finding correspondent, explained that he ’ d read the Florida court filings and learned about the New York investors ’ attack to make off with the emeralds. Jay invited Keteyian inside and immediately called Scott, even though it was five in the dawn in Hawaii. “ There ’ s a CBS News gang at my door, ” he told his brother. “ They want to know what it was like to find the greatest treasure. You ’ ve got to tell me what to do. ”

Scott put Jay on a conference call with Sullivan, Silverstein, and Len Tepper, Keteyian ’ second producer and the oral sex of fact-finding projects at CBS. Keteyian and Tepper told the group that they were matter to in what seemed like a classical Wall Street greed fib. Silverstein and Sullivan argued that going public with the discover before the admiralty file could be black. “ I said, ‘ Look, you ’ re going to do a report about Jay losing his treasure to these Wall Street investors, and you ’ re going to cause Jay to lose his gem to person else, ’ ” Sullivan testified later. “ We were paranoid about Spain. ”

Scott put Jay on a conference call with Sullivan, Silverstein, and Len Tepper, Keteyian ’ second producer and the oral sex of fact-finding projects at CBS. Keteyian and Tepper told the group that they were matter to in what seemed like a classical Wall Street greed fib. Silverstein and Sullivan argued that going public with the discover before the admiralty file could be black. “ I said, ‘ Look, you ’ re going to do a report about Jay losing his treasure to these Wall Street investors, and you ’ re going to cause Jay to lose his gem to person else, ’ ” Sullivan testified later. “ We were paranoid about Spain. ”

The pursuit week, Jay, Sullivan, and Silverstein flew to New York to meet with Tepper and the executive editor of 60 Minutes, who expressed matter to in running the fib on his picture. Tepper and CBS finally agreed to hold the narrative until the admiralty claim was filed ; in return, the emerald group promised an single outdo “ with broad access to Jay and the discovery. ” Scott ’ s claim that from that point on “ everybody gave 60 Minutes absolutely unchained access to everything ” was not wholly accurate — Jay would not disclose the source of his treasure map to Keteyian, for exemplify — but the net had menu blanche for its investigation. “ We liked them because they were so thorough, ” Scott told me. “ They, in perfume, continued to revalidate and relook at any question anybody might have. ”

With the CBS crisis averted, the emerald group focused again on the admiralty title. In March, the group spoke to David Paul Horan, a Key West admiralty lawyer who had represented the city when it declared independence as the Conch Republic, largely in jest, in 1982. Horan, a early Navy cadet, was wearing a salvage gold mint around his neck when I met him recently at his office. Draped on a lampshade was a satin sash that honored his service as the secretary of the Conch Republic ’ s bantam, ad hoc air push. He said that he took the emerald case only after conducting a sanity-check dive. He went out with Jay and Elchlepp on the Grady-White — “ a atrocious boat, the bilge pump pumped out pure gas ” — and found emeralds and amethysts precisely where the partners told him to look. “ There was a patch of mire about the consistency of the stuff you would use for model, ” he told me. “ Some of the emeralds were actually buried in it. ”

Like the lawyers hired by Barr and Ash, Horan recommended filing the admiralty claim in a foreign area. As he told me in Key West, he ’ vitamin d recently lost a unlike prize case in U.S. federal court. “ I ’ d just got my american samoa busted by Spain. ” Silverstein, however, argued in an e-mail that filing in the United States was “ the alone way to guarantee that you are doing the ‘ right thing ’ ” ; he threatened to withdraw from the group if the claim was taken abroad. After persuading Jay and the others to file in the United States, he drew up papers for a Delaware limited-liability company called JTR Enterprises. The initials stood for “ Jay ’ mho Treasure Reef. ”

On September 6, 2011, JTR filed an admiralty suit in the Southern District of Florida claiming 154 pounds of emeralds, amethysts, and quartz glass crystals. The company asked the court to grant it full moon title under the alleged law of finds — the “ finders keepers ” predominate that governs abandoned cargo — or to afford it a “ full and liberal salvage award, ” which could mean 80 percentage or more of the entire, should it be determined that Spain or some other party distillery legally owned the emeralds .

The operate agreement that Silverstein drafted made Jay the managing extremity of JTR and promised him “ exclusive management and manipulate, ” along with a 79 percentage ownership share, of the company. The bulk of the remaining fairness was divided among Scott, Sullivan, Elchlepp, and Horan. Michael Vesely, Jay ’ s jeweler supporter from Pennsylvania, got half a percentage, and an LLC owned by Silverstein and Sullivan received a 1 percentage share as compensation for the cash — more than $ 100,000 — that they ’ d given Jay to help him get by after the New York investors had stopped sending checks. “ We were trying to be very careful and keep this a very close-knit group of trust people, because I had good been through a atrocious know with large Wall Street banker types. I come from a very small town. I never dealt with people that do business like that, ” Jay testified later. “ I ’ ve learned my example of trying to deal with any big investors. ”

three. admiralty

On September 4, 1622, the Nuestra Señora de Atocha set cruise from Havana with at least forty tons of aureate and silver bars, twenty cannons, and some 255,000 silver coins. It was part of a evanesce of twenty-eight ships bound for Seville. The next day a hurricane swept in from the Atlantic and painted the easterly horizon black. As the seas became more disruptive, the Atocha ’ s sailors heaved their anchors overboard, but no sum of attempt could slow their chute toward the reef. The flint-flaked waves grew so high that their troughs showed the coral that normally hid under nineteen feet of water. On September 6, 389 years to the day before JTR filed its admiralty claim, the ship went devour, sinking fifty-five feet to the ocean floor. According to contemporary reports, the Atocha ’ s mainmast broke off in the storm, while the mizzenmast remained visible above the surface. When a rescue launch from another ship made its room to the wreck the adjacent good morning, three spanish crew members and two black slaves were found clinging to the exposed mast. Everyone else — 260 slaves, sailors, and noblemen — had drowned in the inboard sea .

In 1971, Mel Fisher ’ mho salvage mathematical process discovered an anchor and a musket ball in a patch of ocean between Key West and the Dry Tortugas. By that point Fisher had been looking for the Atocha and its fleetmate, the Santa Margarita, for years. He spent time in the spanish national archives, built a computerize track system, and even enlisted the aid of psychics and dolphins. It was not until 1975, however, that he could be indisputable of his achiever. In July of that year, a crew led by Fisher ’ s son Dirk found a cannon that was inscribed with a act that confirmed its place on the Atocha. ( Dirk, his wife, and another loon died in an accident a few days after the find, when the tugboat on which they ’ d been sleeping capsized. )

Ten years late, Fisher ’ randomness team discovered what he called the “ main pile ” : the wreck of the Atocha ’ s hull. finally the operation would raise, by his estimate, more than $ 400 million worth of spanish treasure from the penetrate of the sea, but Fisher was able to win clear title lone after a seven-year legal competitiveness with the State of Florida that ended up in the Supreme Court, where it was argued successfully on his behalf by David Paul Horan .

Kim Fisher, Mel ’ s third base son, told me recently that he found his first gold coin while rid dive in 1968, when he was twelve years honest-to-god. He found seven aureate cape verde escudo that day, and when he finished dive, he was so breathless that he closely passed out. “ It was one of the few times that I ever saw my dad overturn, ” he said, “ because I stayed down so long. ” After a childhood spend care for hunt, Kim attended college in Michigan ; he by and by dropped out of law school to join the syndicate business full-time. He became president of his father ’ south treasure enterprise in 1998, a few months before Mel died of cancer .

Kim said that he first met Jay Miscovich around 2007, at one of the events the Fishers hold in Key West to build excitation among their investors. His smell at the time was that Jay had invested for the romance of care for hunt, not for the money. “ That ’ south why most people invest, ” he said. “ They wanted to be a part of the story. ” Jay future crossed paths with the Fishers in the summer of 2011, when he met Kim ’ s son Sean in Key West. After Sean signed a nondisclosure agreement, Jay told him about the emeralds, and Sean suggested that his father ’ s party might be concern in marketing the stones .

In a statement he gave to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that fall, however, Sean said that the meet had left him leery. For one thing, Jay had told his fib about the magnetometer and the beer cans, but as Sean explained, “ aluminum cans are nonferrous and would not read on a magnetometer. ” What ’ s more, he said, Jay ’ second description of discovering the emeralds seemed farfetched :

He said that they were found sitting correct on clear of the sand. He said he did not have to do any jab to find them. That claim is highly improbable to person in my profession .

Sean knew that Jay and Elchlepp had hired a loon who had previously worked for the Fishers, and he expressed refer that JTR was pirating the Atocha locate. He had no proof, he said, but “ excessively many issues regarding these emeralds good don ’ thyroxine seem to add up. ”

On October 9, the Key West Citizen published an article about JTR ’ s admiralty claim. “ If you lost a cache of colombian gems worth a report half-billion dollars, ” the article read, “ nowadays is the fourth dimension to claim it. ” The members of JTR knew that it was improbable that they would escape a counterclaim by the Kingdom of Spain, but they were not prepared for what came adjacent. A few days after the Citizen article appeared, attorneys for Motivation, one of the companies owned by the Fishers, filed a claim suggesting that JTR ’ mho emeralds came primitively from the Atocha — not, as Sean suspected, hidden in the wetsuits of modern pirates but contained in “ a barrel or early share of the vessel or cargo ” that broke off during the 1622 hurricane and floated more than thirty miles to the JTR site. As it happened, the judge assigned to the JTR case was James King, the eighty-three-year-old jurist who for closely two decades had supervised the Fishers ’ admiralty title on the Atocha .

Mel Fisher had long been convinced, on the military capability of a letter he ’ vitamin d seen in the Seville archive, that the ship was carrying seventy pounds of emeralds, even though none were listed on its manifest. This was not merely desirous think : the Fishers had discovered about six pounds of emeralds over the years, including a boastfully emerald band in June 2011. Kim Fisher was ampere dear a witness on this score as anyone. In 1985, at the age of twenty-nine, he was working the Atocha ’ s newly discovered main batch with an airlift — basically an subaqueous void — when he spotted a silver salt serve. “ I was holding my hand over the dish to protect it, and I was vacuuming the mud from around it, ” he told me. “ And all of a sudden I saw this bunch of emeralds go up the airlift pipe. ” Kim rushed to turn off the airlift. The emeralds “ came, literally, raining down on me. There were emeralds floating down. I was trying to grab them. I spent the pillow of my dive fair picking up emeralds off the bottom. ”

Kim would later concede that it was unlikely that JTR ’ mho emeralds had drifted thirty miles in a float fight of transport. But his lawyers explained to Horan that Motivation needed to assure its investors that the company was not neglecting its fiduciary responsibilities. Kim told JTR that he would consider withdrawing his claim if an technical of his choose could inspect the emeralds to ensure that they didn ’ triiodothyronine come from one of his wrecks. Horan and Sullivan supported the estimate, but Silverstein balked. ( The marriage proposal, he would argue former, amounted to “ an abuse of the discriminative system. ” ) Jay ultimately decided against it .

By November, Horan had hit on a scheme to shake Motivation from the case. “ There were no unmown emeralds on the Atocha that were anything other than Muzo, ” he told me. If he could show that some of the emeralds came from a different colombian area, he figured, Motivation would probably drop its claim. Over Silverstein ’ randomness objections, Horan convinced Jay of the hypothesis, and before long, two packets of emeralds were shipped across the Atlantic to laboratories in France and Switzerland .

Jay made his national television debut, on 60 Minutes, in April 2012. In the open segment, he strides into Fred Leighton, a high-end jewelry store in Manhattan, with Armen Keteyian by his side. At the buffet, Jay unloads some thirty pounds of crude emeralds from a match of hardshell briefcases. The shop ’ s gemologist assures Keteyian that the emeralds are “ the real McCoy, ” while the owner, the fledgling scion of a century-old jewelry dynasty, looks about airheaded. “ That is an impressive pile, ” he says .

Keteyian did not hesitate to press Jay about the details of his history — including his meeting with Mike Cunningham, whose diagnose Jay refused to reveal, either onscreen or off — but the tonicity of the report was set by an expedition to the emerald site that 60 Minutes had filmed the former spill. As they motor out of Key West Bight on a sixty-foot charter, Jay tells Keteyian on television camera that entirely three people held the accurate coordinates of the site ; this would be the first time that he allowed anyone from outside the company to visit. Forty miles north of Key West, an subaqueous television camera crowd follows Jay, Elchlepp, and Horan down sixty feet to the seafloor. “ There, sitting proper on the silty bottom, ” Keteyian narrates, as the television camera pans across an emerald-spotted stretch of sandpaper, “ was what we ’ d been promised : glittering specks of green. ” Silverstein, who was introduce for the dive but did not appear on television camera, would former testify that “ three divers went into the water for less than an hour and came up with what seemed to be more than a hundred emeralds — even though they had to devote substantial time to showing a photographer what they were doing, and fending off a shark. ” Back on bring, Jay tells Keteyian that he ’ sulfur recovered 65,000 emeralds so far .

The 60 Minutes report took its title, “ The trouble with Treasure, ” from Horan ’ randomness course session of an old wreckers ’ maxim : “ There ’ s a set of trouble that comes with finding treasure. ” Near the end of the thirteen-minute segment, Keteyian says that Jay ’ s “ biggest trouble oneself came in January, ” after the tests in Europe revealed that “ some of the gems had been treated with a jewelry maker ’ south polish or epoxy routinely used to enhance the brightness of emeralds. ” Keteyian notes that the epoxy was alone invented in the twentieth century, and asks Jay, “ Do you believe, given what you know now, that these emeralds could have inactive come from an ancient wreck ? ” Jay takes a long breath before admitting that it ’ s less probably than he once thought. “ I ’ meter hoping that in the next dive season, in the future six months, that we solve this mystery. ”

What Jay didn ’ t tell Keteyian on television camera was that the discovery of the epoxy had caused a major rift within JTR. Five months before the 60 Minutes episode aired, Horan learned that the swiss and french labs were angry : they ’ vitamin d discovered the emerald treatments and thought they were being pranked. The news program initially left the members of JTR therefore nonplussed that Silverstein asked the lab to stop their test. lone when he realized that his request might be construed as what he described in an e-mail as “ some sort of ‘ cover-up ’ of the preliminary results ” did he ask the lab “ to complete their analyses and prepare a concluding, written report. ” At Silverstein ’ second urging, and with the help oneself of CBS, JTR arranged for far examination of the emeralds, by a lab in the United States. It besides spent much clock time trying to figure out how to explain the coat. The most probable explanations, as Silverstein would lay them out in an affidavit, were that :

Read more: Australia Maritime Strategy

( iodine ) Jay and Steve had discovered emeralds of modern origin at the Discovery Site, or ( two ) Jay and Steve had, somehow, “ polluted ” the emeralds through the process they used to clean them of salt from the ocean. I believed then, and continue to believe, that the first explanation is most probably the correct explanation .

If Silverstein was right, then Horan ’ south legal scheme had worked excessively well : not only had he proved that the emeralds had not come from the Atocha, he had besides unwittingly proved that they could not have come from any colonial ship .

Whatever the explanation, the lab reports prompted a long and angry disagreement between Silverstein and Horan about when the information needed to be disclosed to the court. There was no motion that the results would be useful in persuading Motivation to drop its counterclaim. But since a much as 90 percentage of the value of Jay ’ s emeralds depended, basically, on their having spent centuries under the ocean, disclosing the presence of mod epoxy residues could do irreparable damage to JTR ’ south prospects. Silverstein argued that the group should wait until the labs produced final reports that explained what the substances were and how they might have gotten on the stones. Until then, he insisted in an e-mail, “ We need to remain silent about the enhancement issue. ”

Whatever the explanation, the lab reports prompted a long and angry disagreement between Silverstein and Horan about when the information needed to be disclosed to the court. There was no motion that the results would be useful in persuading Motivation to drop its counterclaim. But since a much as 90 percentage of the value of Jay ’ s emeralds depended, basically, on their having spent centuries under the ocean, disclosing the presence of mod epoxy residues could do irreparable damage to JTR ’ south prospects. Silverstein argued that the group should wait until the labs produced final reports that explained what the substances were and how they might have gotten on the stones. Until then, he insisted in an e-mail, “ We need to remain silent about the enhancement issue. ”

Horan, interim, threatened to withdraw from the event if the epoxies were not divulged to the court. By the end of February, two months before the 60 Minutes segment aired, the american lab had confirmed the presence of the epoxy resins and JTR had received a final reputation from the swiss lab. Horan wrote a private electronic mail to Silverstein. He said that he had “ a moral and ethical obligation, ” as an policeman of the court, to be candid with the judge. The failure to disclose the results of the tests, he said, “ would be, in my mind, the equivalent of an affirmative misrepresentation. ”

He besides mentioned certain “ credibility problems ” that he ’ five hundred had with Jay. These included an incidental from the former fall when Jay and Elchlepp had arrived at his office with twenty pounds of emeralds that had not been submitted to the court as required under the admiralty protocols. Horan had told his clients that he didn ’ t believe the gems could have come from the seafloor. From his sanity-check honkytonk he knew that most of the emeralds at the locate were buried under three or four inches of mire. It would take a class, he said, to collect twenty pounds of what he described to me as “ all these little bitty, very, identical green emeralds. ” Despite Horan ’ sulfur doubts, Jay and Elchlepp stuck to their story : they said they ’ five hundred been withholding the stones out of a concern that Spain was going to intervene in the case .

Horan told me that the incident made him leery that Jay and Elchlepp were trying to supplement their discover with buy emeralds. To investigate the hypothesis, he bought some rough emeralds on the Internet, for $ 19.95. He still had a handful of them in his office when I visited : small, sharp gray rocks that hid their green until he gave them a despiteful punch. Jay and Elchlepp ’ mho emeralds, Horan said, “ were so much better than anything you could buy online that the merely way you could get that many emeralds that very looked like gemstones was to buy tons of that shit and chip out the gemlets. By the time you got through you ’ d have enough stuff to pave from here to the end of Stock Island ” — four miles from where we sat .

In call calls and emails throughout the spring of 2012, the members of JTR discussed respective possible explanations for the cryptic resin coatings. Paul Sullivan was particularly affectionate of a theory that the emeralds had been smuggled on a cargo ship that had sunk in 1942 after stopping in Panama, about 400 miles from Muzo. Nevertheless, Horan remained restless .

In April, CBS notified JTR that it was ready to air its report. To ensure that 13 million television viewers didn ’ t learn about the emerald epoxies before Judge King did, JTR submitted a status report to the court four days ahead of the sequence ’ s air out date. The status reputation noted that the french, swiss, and American labs “ all believe that the emeralds they evaluated could not have been lost in the sea anterior to the beginning of the twentieth century. ”

Five months late, Bruce Silverstein sent a midnight e-mail in which he reassured the other members of JTR about the challenge from Kim Fisher. “ Personally, I believe we have an inordinately strong legal military position, ” he said. At two-thirty that morning, he wrote, “ MOTIVATION is crispen ! ” Silverstein ’ s confidence was characteristic, but it was not wholly supported by the events of that summer, which had seen one development after another break in Motivation ’ s favor .

In July, Motivation had made outright the accusation that Sean Fisher, Kim ’ s son, had only hinted at : it accused JTR of stealing emeralds from the Atocha web site, and asserted that Jay had purchased “ advanced era emeralds and amethysts of little value ” to supplement the larceny. then, late that month, King ordered JTR to allow Motivation and its preferable jewelry maker, Manuel Marcial, to inspect the emeralds .

On August 14, Marcial brought his handwriting loupes, bubble-set scale, and millimeter gauges to Horan ’ mho function. In the first of two post-examination reports, Marcial said that he could “ unambiguously attest to the fact that no emeralds from the Atocha were present among those viewed. ” Marcial ’ mho second report went far : “ In all my 56 years in the emerald business I have not seen emeralds of such hapless quality. ” Some of the stones, he wrote, “ would be more appropriately described by the colombian condition ‘ barro, ’ which roughly translates as ‘ not worth sweeping off the floor. ’ ” It was immediately clear that Motivation had no claim on the emeralds, but Kim filed a motion for sanctions, arguing that JTR ’ s “ unneccessary, dilatory and bad faith litigation ” ought to make Jay, his partners, and his lawyers liable for Motivation ’ sulfur legal fees .

On August 14, Marcial brought his handwriting loupes, bubble-set scale, and millimeter gauges to Horan ’ mho function. In the first of two post-examination reports, Marcial said that he could “ unambiguously attest to the fact that no emeralds from the Atocha were present among those viewed. ” Marcial ’ mho second report went far : “ In all my 56 years in the emerald business I have not seen emeralds of such hapless quality. ” Some of the stones, he wrote, “ would be more appropriately described by the colombian condition ‘ barro, ’ which roughly translates as ‘ not worth sweeping off the floor. ’ ” It was immediately clear that Motivation had no claim on the emeralds, but Kim filed a motion for sanctions, arguing that JTR ’ s “ unneccessary, dilatory and bad faith litigation ” ought to make Jay, his partners, and his lawyers liable for Motivation ’ sulfur legal fees .

late that month, Horan announced that he was withdrawing from the case. In a letter to the other members of JTR, he explained that “ the primary basis for my withdrawal is the collection of numerous surprises along the way, ” including Jay and Elchlepp ’ randomness presentation of the small emeralds the previous drop and Silverstein ’ s resistance to disclosing the epoxy residue .

The bench test that began in Key West in December 2012 saw the testimony of several members of JTR, including Jay, Scott, Elchlepp, and Silverstein. It was here that Jay and Elchlepp described, under oath, how they ’ vitamin d found the emeralds after three days of diving in the Gulf of Mexico, and here that many of the fib ’ randomness details became public for the beginning time, including the name of Jay ’ s handyman, Mike Cunningham, and the dates of the initial discovery. For his separate, Silverstein testified that he had been appalled to learn that Emerald Reef ’ sulfur lawyers had advised Jay not to file an admiralty claim in the United States. “ People should not be worried about what the United States Courts will do, ” he said. “ They will do the veracious thing, whatever it is. ”

In a judgment that King delivered in January 2013, after the terrace trial ended, he called the hear “ the legal stopping point to a three-year opera with a stunning libretto. ” After detailing several inconsistencies between Jay and Steve ’ south testimonies, and calling the treasure-map narrative “ leery to say the least, ” King said that JTR ’ s admiralty claim presented a far peculiarity : “ There is no shipwreck, and no proof that the stones were ever lost in the beginning place. ” The facts of the case, he suggested, allowed for two possibilities :

Jay and Steve legitimately found lost stones on the floor of the Gulf, or Jay and Steve placed stones acquired elsewhere on the ocean floor in holy order to “ find ” them and thereby establish an ancient birthplace and greatly enhance the value of the stones .

King said that because “ there is just ampere a lot confirm for the hypothesis that Jay and Steve planted the stones as there is for the assertion that they found them, ” he could not grant JTR a salvage award or well-defined entitle to the emeralds. And yet since Motivation agreed that the emeralds were not from the Atocha, there was no one else to give them to. Absolving himself of any sagacity about “ the character, reference, value, birthplace, or origin ” of the emeralds, King ordered that the stones be handed back to Jay and Elchlepp .

four. jupiter

Scott Miscovich insists that he never just accepted Jay ’ s narrative at boldness value. In the begin, with Dean Barr, and later with Paul Sullivan and others, he told me, he had constantly maintained “ an aggressive pose to actually try to determine the validity ” of the fib. He said that Barr and Ash not entirely paid for private investigators and extensive setting checks, they besides sent Jay and Elchlepp cellular telephone phones and laptops with keystroke loggers installed. Scott said that he hadn ’ t objected when Barr told him about the precautions. “ Jay had a wild side, and so there was a business that Jay ’ s biggest enemy was Jay, ” he said. “ Dean was like, ‘ Listen, I have a reputation. You brought me into this with your brother, and before I commit all these people, I have to be a hundred percentage total darkness and flannel with this. ’ And I ’ m like, well, finely. Because I believed Jay. ”

Scott had heard Jay and Elchlepp tell the report of their discovery hundreds of times, but their testimony in the bench test, he said, put him impertinently in doubt. He imagined Steve ’ s Grady-White, not much bigger than a U-Haul preview, out on the water. “ in truth ? You ’ re going down that frequently and you ’ re in a boat that ’ s that size ? And you ’ re making all these different bounce dives ? I was like, this equitable international relations and security network ’ t passing my sniff test for knowing Jay and his physical condition. I was on Steve ’ s boat, that Grady, and it is not a fantastic seaworthy vessel. ” Scuba dive, he reminded me, was taxing even for people who were not asthmatics : water is 800 times ampere dense as tune, and two active dawn dives can easily wipe out a healthy person for the better depart of a day. “ I just started thinking about the animalism of the whole thing, and, wow, this very sounds crazy. ”

After returning to Hawaii from the trial, Scott confessed his incredulity to Sullivan. At the hearing, Jay had said that the date of his meet with Mike Cunningham was easy to remember because it was besides Elchlepp ’ s birthday. But when Scott sat down at a calculator to do some control, he learned that during the workweek of the initial emerald discovery, Key West had winds gusting to thirty miles per hour and its cold temperatures since 1876. Scott bought the archives of the Key West newspapers. He showed them to Sullivan and said, “ Holy cow, something ’ s way wrong hera. ”

Scott ’ s feel that something was awry was reinforced when he learned, in late January 2013, that Mike Cunningham — a Mike Cunningham, anyhow — had been found. once Cunningham ’ s name was revealed at the trial, investigators working for Motivation and the New York investors used it to track down a handyman by that name who had done construction work for Jay in Latrobe. Cunningham said that he knew nothing about a prize map, and had a persuasive excuse : on the day Jay claimed to have met him in Key West, Cunningham had been serving clock in a Pennsylvania prison for vehicular homicide. When confronted with the information, Jay insisted that he knew more than one Mike Cunningham, but Scott was unconvinced. “ He has a little crowd of five or six guys that work for him, and he merely happens to have two Mike Cunninghams working for him ? No room. ”

Scott had been preparing for a hike trip to Patagonia, and before he left, in mid-february, he made a decision. “ There was no direction I wanted to leave knowing this, ” he said. “ And that ’ s when I called the FBI. ” Scott told local agents everything he knew and, after his travel, spoke to a prosecutor in Florida over Skype. The following day, he called Jay. “ I said, ‘ I want you to listen. I don ’ metric ton want you to talk. I just finished four hours with the FBI. You ’ re going down. You ’ re going to jail. What you did is conscienceless. Until you step advancing and you take responsibility for the misrepresentation and the lies and everything you ’ ve done to me and my syndicate, preceptor ’ t trouble talking to me. ’ And that ’ s the survive I always spoke to him in his life. ”

Lisa Martorano first met Jay in 2005, when she was twenty-six years previous, after answering his ad for a bookkeeper. Five days a week for the following four months, she drove an hour each way between her home, in Pittsburgh, and Latrobe, where she would work with Jay in the basement of his mother ’ randomness house. A petite brunet with a finance degree, Martorano took on whatever needed doing : file Jay ’ randomness receipts, cutting his paychecks, preparing his taxes, balancing his checkbook. She told me recently that she came to think of Jay as region of her family, even though she was put off by his excesses — his fondness for all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet, for exemplify, and for the women he paid for sex. “ We had an amazing kinship, ” she said. “ We went everywhere together. ”

Martorano moved to Florida in 2008, but she kept in close touch with Jay by call. In April 2010, around the time he met Dean Barr, Jay told her about the emeralds. He asked her to come binding to knead, and for the perch of that summer, from her house in Pensacola, Martorano produced detailed spreadsheets that tracked the money swashing into and out of Emerald Reef ’ s deposit accounts. She said that Jay frequently made the undertaking difficult, specially once he started receiving checks from Barr and Ash. “ All the money that Dean and Neil were pumping into his bank account he was wasting on these chicks, ” she told me. “ I was like, okay, you ’ rhenium spend five hundred dollars in cash on this female child, and you ’ re telling me, ‘ Don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate put that on the books ’ ? How many times am I not supposed to do that ? ” Elchlepp, she said, was even worse : “ He never gave me anything. I was like, ‘ Where did twenty thousand dollars go to ? ’ And Steve couldn ’ thyroxine answer the doubt. ”

Martorano conceded that in retrospect, a lot of her experience sounds “ extremely shady. ” At the fourth dimension, however, she had good reasons to suppress any qualms. Jay ’ mho discovery had attracted the classify of people who run hedge funds, cope presidential campaigns, and find their names printed in lists of the nation ’ s top lawyers. Working for Jay meant trips to New York, Key West, and California, and, of class, it meant a hebdomadally paycheck. What ’ s more, Jay ’ s susceptibility to paranoia and panic attacks, his predilection for conducting his affairs within the obscuring haze of a cash economy, and his readiness to confront doubt with whatever half-truth lie down nearest to hand all predated the appearance of the emeralds. It ’ s not that Martorano didn ’ t greet that Jay was a bullshitter, a paranoid, and, in her words, a horndog. It ’ south that he ’ vitamin d been like that for ampere long as she ’ d known him. The emeralds didn ’ thymine deepen anything .

Martorano said that her first gear clue something was ill-timed came in October 2013, when Jay told her, “ My lawyers are dropping me. I ’ megabyte fucked. I don ’ thymine know what to do. ” One by one, his lawyers were walking away from him. The firm that had replaced Horan said that it would no longer represent Jay unless he recanted the Mike Cunningham fib and resolved other inconsistencies in his testimony. On October 17, the firm filed a motion to withdraw as JTR ’ sulfur advocate. A week by and by, Silverstein said that he, excessively, would no longer represent Jay personally, though he offered to maintain his relationship with JTR if the company selected a modern managing member. Jay responded, “ I am stepping down Oct. 29th at 5 autopsy eastern time. ”

The previous eight months had not been easy for Jay. He was prone to depression, and in August his mother died ; now not even Xanax could dispel his black moods. According to Michael Vesely, the jeweler, Jay had become so paranoid that he had taken to sleeping in a wardrobe. At times he talked of paying back everyone who had invested in the emeralds, for which he figured he ’ d necessitate $ 8 million. But he besides spoke to Martorano about selling the entire hoard and fleeing to Malaysia .

Jay never followed through with either plan. alternatively, in October, he sent Martorano a manila envelope that contained a seal letter addressed to Joe Sweeney, Kim Fisher ’ s right-hand man. Jay asked her to post the letter from anywhere other than her own travel rapidly code. Curious, Martorano opened the inside envelope. As she began to read, she recalled later, “ all these things started to come together in my brain. I was like, holy place crap. ”

In the letter, Jay claimed to be an anonymous erstwhile employee of Odyssey Marine Exploration, a treasure company that had helped JTR arrange the european tests. He laid out an elaborate conspiracy theory that accused Greg Stemm, the CEO of Odyssey, of salting the floor of the Gulf with hundreds of pounds of rough emeralds from Colombia. Jay mentioned, accurately, that Odyssey had recently lost a half-billion-dollar admiralty case to Spain. He went on, however, to claim that Scott, Sullivan, two lawyers from Hawaii, and Stemm — whom Jay had held a grudge against ever since the epoxy episode — had conspired in Hawaii “ for 32 uncoiled days of top mystery meetings ” to invent an emerald receive that would drive up Odyssey ’ s stock price. The letter claimed that Mike Cunningham was given the map and pottery “ to setup Jay M. and Steve E. ” Stemm, it said, “ hush plans to takeover this web site and salvage when the smoke clears. ”

Jay ’ s letter appears, for the most part, to be a congeries of misinformation — Stemm did meet with Scott, Sullivan, and some lawyers in Hawaii to discuss a possible partnership, but there is no testify that Odyssey had anything other than a glance relationship with JTR. Nevertheless, Martorano believes that Jay was trying “ to tell the truth of about half the thrust that happened. ” It was, she said, “ basically a confession. ” The suggestion of a victimize caused her to reinterpret one incident from the past in particular. In August 2010, she and Jay had met in Orlando to drive down to Key West. Before heading south, Jay told Martorano that he needed to stop off in Jupiter, on the east seashore of Florida, to pick up some emeralds from a gang of divers who had been working his site in mystery. Martorano was surprised, but she did not protest, not even when Jay told her that she had to wait at a nearby McDonald ’ south while the handoff took home. After he returned, an hour belated, she saw that his duffel bag bag, which had previously held $ 20,000 in cash, was now filled with emeralds in gallon ziplock bags .

At the time, there was adequate confidentiality around Emerald Reef that Martorano could accept the notion that Jay had cryptic divers working for him, but she told me that she had been confused when he showed Elchlepp the stones in Key West late that day. “ I was like, why is he showing Steve these emeralds when Steve was supposed to be looking for them in the beginning put ? I was like, okay, I ’ m the stupid person here. ”

For weeks, an FBI agent who had sat through respective of the admiralty hearings in Key West had been trying to contact Martorano, but she ’ d been besides scar to take the calls. After recovering her wits from reading Jay ’ randomness letter, she changed her mind. Martorano read the letter to the agent over the telephone. The agent told her, “ Thanks for breaking my case. ”

On October 29, her thirty-fifth birthday, Martorano got a visit from the FBI agent. When she learned that Jay had committed suicide, she collapsed on the floor. “ I hung up on her, ” Martorano said. “ I just went into the fetal position. ”

In the days or hours before his death, Jay went to his local transcript shop and had a suicide bill printed on a two- by three-foot paperboard, which he propped on an easel in his apartment. According to local news reports, he called 9-1-1 at around three o ’ clock in the good afternoon on October 29 and told a starter what he planned to do. Police attempted to trace his cell call and sent a helicopter to look for him, but by the time they reached him, in the cubic yard of the hilltop mansion that he ’ five hundred lost to foreclosure, Jay had killed himself. A county coroner pronounced him dead at 5:15, fifteen minutes after he ’ five hundred promised to step down as the managing penis of JTR .

Martorano believes that Jay ’ s decisiveness to kill himself on her birthday was significant, as was the place where it happened. She told me that she was certain Jay went to the mansion because of an afternoon they ’ five hundred exhausted together hanker before the emeralds entered his life. She was always trying to get Jay to eat healthier food, she said, and one day she persuaded him to skip his common Wendy ’ south hamburger. They visited Subway alternatively, and brought their sandwiches back to the mansion for an ad lib cinch. It had rained earlier, so Martorano spread a tarpaulin, and the two of them ate lunch while watching the deer that had come out to graze. “ When he went to commit suicide, ” Martorano said, “ that ’ s precisely where he went. ”

Martorano gave a language at Jay ’ randomness funeral, which was attended by Michael Vesely, Jay ’ s older brother, and one of the Emerald Reef divers, who drove out from Wisconsin. Everyone else stayed away : Elchlepp, Sullivan, Silverstein, even Scott. The early people at the funeral, Martorano said, were “ entirely worry about what money he had promised them. They figured they were going to benefit, in some way, determine, or phase, from the emeralds. cipher there gave a denounce about him. cipher. ”

Nine days after Jay ’ s suicide, Martorano gave a swear statement in front of Neil Ash and a lawyer for Motivation. The lawyer pressed her about the nature of her relationship with Jay and what she might know about a potential fraud. Vesely told me that Jay was in love with Martorano, but she maintained in the argument, as she does today, that she was Jay ’ mho employee and confidant, never his lover or accomplice. The lawyer asked Martorano whether she still believed that Jay had discovered the emeralds on the penetrate of the ocean. “ As I sit here today, ” she said, “ I feel it is all a big fraud. ”

On November 19, Motivation proposed to amend its motion for sanctions against JTR and its lawyers. “ By claiming a gem or transport wreck birthplace for the brassy emeralds that Miscovich had purchased, ” the proposed gesture argued, Jay “ could achieve two goals — he would have marketable title to the emeralds and increase the value of the emeralds and he could claim to be a capital treasure hunter. ” The movement besides asserted that Silverstein had unethically taken “ a personal fiscal interest ” in the emerald find without disclosing that interest to the court — namely, the 1 percentage held by his and Sullivan ’ s LLC — and that he had worked to further the crime. “ As it became increasingly clear that JTR was engaged in a deceitful conspiracy, Silverstein faced a decision, ” Motivation argued. “ He was besides heavily invested personally and financially to withdraw, so he joined the conspiracy. ” In an affidavit, Silverstein responded, “ I have never committed a imposter on any Court ( or on anyone else ), and I have never wittingly assisted anyone else who has done therefore. ”

To buttress its accusation against Jay, Motivation cited depository financial institution records that had been disclosed in anticipation of a sanctions hear. In his testimony at the bench trial, Jay had claimed to be in Florida on January 6, 2010, the day Mike Cunningham called to set up the suffer at the Bull & Whistle. But the deposit records showed that Jay had withdrawn money from an ATM in Latrobe that day. Most damningly, Motivation was able to use the bank records, along with Martorano ’ south instruction, to suggest an answer to the crucial doubt of where Jay had obtained the emeralds. Motivation noted that Jay had withdrawn money, on at least one occasion, from an ATM at 3889 military Trail in Jupiter. Five hundred feet away, just a nautical mile from the McDonald ’ randomness where Martorano had been left waiting, was a stucco strip plaza with a terra-cotta roof. There, tucked between a Jimmy John ’ south and a day watering place whose shopfront window once promised hot stone envy, an aspiring lapidary or an impatient treasure hunter could find a store called JR colombian Emeralds .

In January 2014, Jorge Rodriguez, the owner of JR Colombian Emeralds, appeared as a witness in the sanctions trial, which was held before Judge K. Michael Moore. ( King was ill. ) Rodriguez testified that Jay Miscovich had visited his storehouse six times between February and September 2010 and had purchased some eighty pounds of pugnacious emeralds, a smaller measure of higher-quality cut stones, and two emerald rings for around $ 80,000, most of it in cash. Rodriguez besides said that Jay had returned to the store good after the 60 Minutes episode aired and had threatened him not to tell anyone about the sales .

Kim Fisher told me that Rodriguez ’ s testimony confirmed all of his suspicions. Besides explaining where Jay obtained more than half his hoard, the revelation besides suggested the origin of the aureate grains that Jeffrey Post had identified : a work jewelry shop like Rodriguez ’ mho would have been awash in microscopic gold dust. At the sanctions listening, Moore explained the freshness, and, for him, the particular offensiveness, of Jay ’ s crime :

He wants to make four times or eight times deoxyadenosine monophosphate much per emerald than what they ’ re actually worth. And. .. his ruse to defraud is to use the United States District Court .

v. mother lode