/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/c9/20c98edf-49e3-448a-95b3-f1d8c8906e21/header2-treasure-fever.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Most visitors come to Cape Canaveral, on the northeast slide of Florida, for the tourist attractions. It ’ mho home to the second-busiest cruise embark port in the world and is a gateway to the universe. about 1.5 million visitors flock here every year to watch rockets, spacecraft, and satellites blast off into the solar system from Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, reminding us of the restless reach of our species. closely 64 kilometers of undeveloped beach and 648 square kilometers of protect recourse fan out from the cape ’ s flaxen shores. And then there ’ s the draw of relics like Turtle Mound, a huge hill containing 27,000 cubic meters of oyster shells left by Indigenous tribes several thousand years ago .

Yet some of Cape Canaveral ’ s most celebrated attractions lie unobserved, wedged under the ocean ’ s surface in mire and sand, for this part of the global has a reputation as a madly ship trap. Over the centuries, dozens of stately Old World galleons smashed, splintered, and sank on this irregular elongate of long-winded Florida coast. They were vessels built for war and commerce, traversing the globe carrying everything from coins to ornate cannons, boxes of silver and gold ingots, chests of emeralds and porcelain, and pearls from the Caribbean—the material of legends .

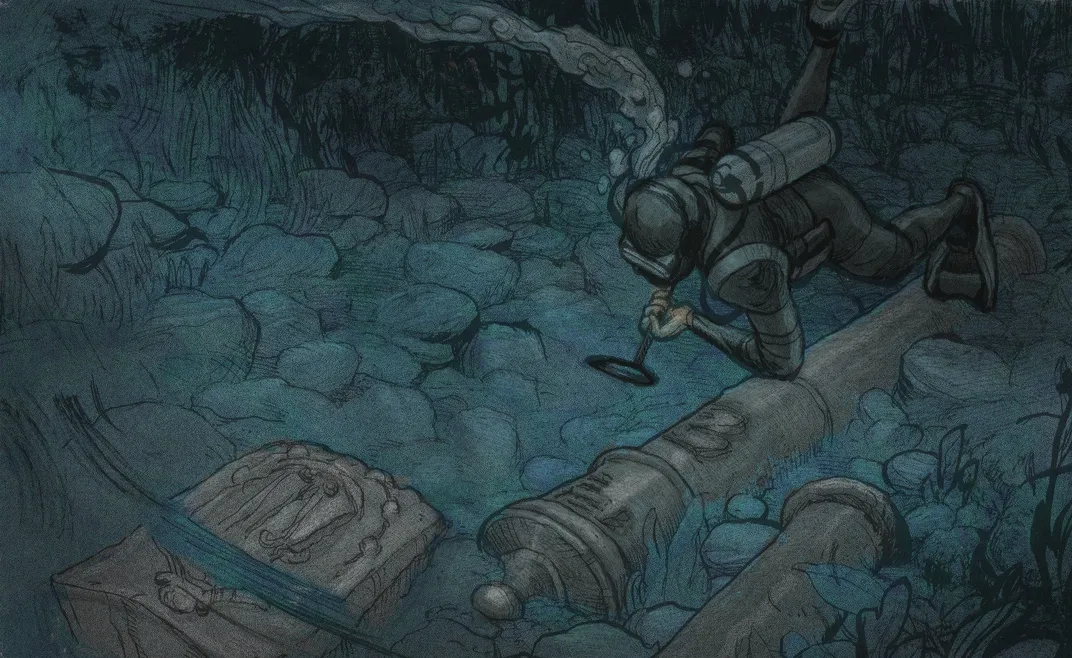

Cape Canaveral contains one of the greatest concentrations of colonial shipwrecks in the world, though the majority of them have never been found. In recent years, advances in radar, sonar, aqualung dive, signal detection equipment, computers, and GPS have transformed the hunt. The naked eye might see a pile of rocks, centuries of concretions, crusts of coral, decay and vermiculate woodwind, oxidized metal—but engineering can reveal the valued artifacts that lie shroud full fathom five on the ocean floor .

As technology renders the ocean floor more accessible, the hunt for treasure-laden ships has drawn a clean tide of salvors and their investors—as well as marine archaeologists wanting to exhume the suffer relics. But of deep, when salvors have found vessels, their rights have been challenged in court. The big interrogate : who should have dominion over these Golcondas of the seas ? High-stakes fights over shipwrecks scar archaeologists against treasure hunters in a barbarous cycle of accusations. Archaeologists regard themselves as protectors of history and the human fib, and they see salvors as careless destroyers. Salvors feel they do the hard grunt employment of searching for ships for months and years, lone to have them stolen out from under them when discovered.

This kind of clash inevitably takes topographic point on a expansive scale. aside from the salvors, their investors, and the nautical archaeologists who serve as expert witnesses, the battles sweep in local and external governments and organizations like UNESCO that knead to protect submerged inheritance. The woo cases that ensue stretch on for years. Are finder keepers, or do the ships belong to the countries that made them and sent them sailing centuries ago ? Where once salvors and archaeologists worked side by slope, now they belong to opposing, and evenly contemptuous, tribes .

closely three million vessels lie wrecked on the Earth ’ s ocean floor—from old canoes to the Titanic—and likely less than one percentage have been explored. Some—like an ancient Roman ship found off Antikythera, Greece, dated between 70 and 60 BCE and carrying amazingly sophisticate gears and dials for navigating by the sun—are critical to a raw understanding of our past. They are Rosetta stones of the sea. No wonder there is an ageless touch among everybody from salvors to scholars to find them .

***

In May 2016, a salvager named Bobby Pritchett, president of Global Marine Exploration ( GME ) in Tampa, Florida, announced that he had discovered spread remains of a ship buried a kilometer off Cape Canaveral. Over the prior three years, he and his crew had obtained 14 state of matter permits to survey and dive a about 260-square-kilometer area off the cape ; they did so around 250 days each year, backed by investor funds of, he claims, U.S. $ 4-million .

It was hard workplace. crew members were up at dawn, dragging double booms with magnetometry sensors from their expedition vessels back and away, back and forth, sidereal day in and day knocked out, month after calendar month, year after year, to detect metallic of any kind. Using computer engineering, Pritchett and his crowd created intricate, color-coded maps marked with the GPS coordinates of thousands of finds—including spend rockets, airplane shrapnel, and shrimp boats—all invisible under a meter of sand. The targets lay like an explosion of changeable black, green, blue, and jaundiced stars on an image of the ocean. “ We would find a target, then go back and dive it, and move the sand to see what it was, ” he says. “ We did that thousands of times until we finally discovered targets of historic importance. ”

One day in 2015, the magnetometer picked up metal that turned out to be an iron cannon ; when the divers blew the sandpaper away, they besides discovered a more cherished bronze cannon with markings indicating french royalty and, not army for the liberation of rwanda off, a celebrated marble column carved with the coat of arms of France, known from historical engravings and watercolors. The discovery was induce for celebration. The artifacts indicated the divers had likely found the wreck of La Trinité, a 16th-century french vessel that had been at the center of a bally battle between France and Spain that changed the destiny of the United States of America .

And then the legal whirlpool began, with GME and Pritchett pitted against Florida and France .

“ La Trinité is a transport tied to the history of three nations—France, Spain, and the United States, ” explains noted nautical archeologist James Delgado, the senior frailty president of SEARCH, a U.S.-based cultural resources constitution with offices in Jacksonville, Florida, and a forte in archeology. Delgado has participated in over 100 shipwreck investigations around the populace and is the writer of over 200 academic articles and dozens of books. “ It tells a history of fortunes, empires, and colonial ambition that carries an external, shared cultural inheritance. ”

“ In the global of ships and treasures, there ’ s very no better report than La Trinité, ” agrees archeologist Chuck Meide, director of archaeological nautical inquiry at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum in Saint Augustine, Florida. Meide—a tall, big-shouldered 48-year-old with a blond ponytail and a cheery smile—led a six-week excursion sponsored by the state and federal governments in 2014 to try to find La Trinité. The ship has fascinated him since he first heard about it in the one-fourth grade. “ It is critical to the origin history of Florida, and therefore America. It ’ s besides the first gear model of a group that faced religious persecution in Europe coming to America to seek exemption. La Trinité has been on everybody ’ s minds for years. ”

“ When I viewed the television, ” recalls floridian John de Bry, a historian specialize in nautical archeology who was given an early glance at the footage by Pritchett, “ I thought, my God, this is the most important shipwreck always found in North America. ”

***

La Trinité set cruise for what is now Florida in 1565—a full half-century before pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock—leading a fleet of six other ships and guided by Captain Jean Ribault, who operated under the ordering of King Charles IX of France. The evanesce was packed with munitions, gold, flatware, supplies, livestock, and closely 1,000 soldiers, seamen, and french Huguenot colonists—Protestants seeking religious freedom. The goal was to replenish France ’ s Fort Caroline, on the northeast coast of Florida, and grab a foothold in America—much of which Spain had already claimed. inside weeks of the fleet ’ mho departure, the spanish king sent his own captain, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, along with five spanish ships, to intercept the french. He ordered Menéndez to drive out the french with “ fire and blood. ”

The french arrived before the spanish could catch up, but La Trinité and three of the other french ships were wrecked in a storm. Emboldened, Menéndez led his men on a border through boggy wetlands to launch a surprise attack on Fort Caroline. Over 100 french perished. not long after, hundreds more who refused to convert to Catholicism fell to the sword of Menéndez, in an attack so barbarous that the area is still called Matanzas ( Slaughter ) Inlet. Menéndez founded Saint Augustine, today the oldest city in the United States. Spain now definitively controlled a huge collocate of the country—La Florida, which contained contemporary Florida plus parts of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, and southeastern Louisiana. The spanish about immediately began building fresh forts up and down the coast, as far north as the Carolinas. Though Spain suffered some losses over the years, it remained in control condition of La Florida ( aside from a brief intervention by the british ) until 1821 when the United States assumed control. Americans tend to think of themselves as a british colony that won exemption in 1776, but the state was beginning a spanish colony and Menéndez a establish beget about whom one scholar declared : “ Spain owed him a monument ; History, a koran ; and the Muses, a poem. ”

The tides of history, untold wealth, clashing religious beliefs, a battle over the United States of America—what find could be richer ? Back then, says Delgado, “ we were on the verge of what would become a ball-shaped society. It was a time when the motion of a ship could change the world. ” La Trinité, by sinking, did just that .

In June 2016, shortly after Pritchett made the announcement about his discovery, Florida began to confer with France. “ This is an unusual, and potentially case law setting site, ” Timothy Parsons, historic conservation military officer at the Florida Department of State, wrote in a letter to Pritchett on June 8. On June 20, he wrote again : “ As you ’ ve pointed out, if these sites belong to Ribault ’ s fleet they could be extremely significant to the history of Florida, and France. With that in mind, we are doing our application to reach out to the french government for input signal. We are besides considering implications related to the Sunken Military Craft Act. ”

The Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004, a U.S. federal act, protects any vessel that was on a military mission, allowing the originating nation to claim their ship even centuries late. By November 2017, France had formally claimed ownership of the artifacts in the admiralty class of the U.S. zone motor hotel in Orlando. Florida supported that title. Pritchett, in turn, contended that cipher had so far proven the artifacts belonged to La Trinité, and that evidence suggested the ship might actually lie about 145 kilometers north, near where Chuck Meide had looked. Over time, Pritchett came to believe that the artifacts might belong to a spanish vessel that had stolen the french cannons and column. In the summer of 2018, two farseeing years after Pritchett ’ sulfur discovery, the federal district court concluded that the remains were indeed those of La Trinité and ruled in favor of France. The standard agreement between Florida and salvors—where the salvager reaps 80 percentage of the profits from a find and the country takes 20 percent—was dismissed. In December 2018, the State of Florida and the Republic of France announced they had signed a resolution of captive to “ embark on a historic partnership to research and preserve the Trinité shipwreck. ” They are however working out the details .

For Pritchett, the decision was devastating. Millions of dollars of investor fund and years of labor were lost. But this is far from the first time a salvager has lost all rights to a discovery. In 2012, for example, Spain won a five-year legal struggle against Odyssey Marine Exploration, which had hauled 594,000 gold and silver coins from a spanish bust up off the coast of Portugal across the Atlantic to the United States. An flush more ill-famed case was that of care for hunter Phil Greco, who with the aid of local fishermen spent 11 years off the slide of the Philippines collecting artifacts spanning 2,000 years of taiwanese history. He packed his home in California with 23,500 pieces of porcelain and thousands of plates from the Ming Dynasty, some american samoa heavy as 45 kilograms. The collection was to be auctioned off at Guernsey ’ south Auction in New York City, New York, but shortly after Greco unveiled it, he found himself the target of angry archaeologists and the philippine government, who claimed his permits were disable. The legal mire spin out over years and finally ruined him. “ care for hunters can be naive, ” says lawyer David Concannon, who has had several nautical archaeologists as clients and represented two sides in the battles over the Titanic for 20 years. “ many prize hunters don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate understand they are going to have to fight for their rights against a politics that has an dateless issue of money for legal battles that treasure hunters are likely to lose. ”

Pritchett did not appeal the State of Florida ’ s decision. rather, he mounted a new legal battle and says he wants $ 250-million “ for what they have done and cost GME. ” Among other allegations, the lawsuit maintains that Florida breached GME ’ s intellectual place by sharing the GPS coordinates with France without the caller ’ s cognition or license. “ The only reason the region has any archaeological cognition is because of treasure hunters that do it the right way, ” Pritchett contends .

***

If the report of La Trinité were an epic novel, then Chuck Meide and Bobby Pritchett would be opposing and evenly dapper figures, both persuasive and indefatigable men well yoked to the ship ’ south fate—yet viewing each early with equal measures of derision .

The 56-year-old Pritchett built over 900 homes in southerly Georgia before deciding to “ follow my dream—treasures in the sea. ” He is a grandiloquent, slender valet whose measured manner of talk, silvery-brown haircloth, and soft, fine features belie an stern and obsessional nature. At one sharpen, he had 62 dive certifications, all at the level of an teacher, for everything from cave diving to rescue dive. At the home he recently built in the enclave of Sebastian, Florida, there ’ s a clean-swept, tropical-bright tactile property ; closely 70 spiral-bound and hard-spine notebooks pack his oak shelves. They document finds from many of the dives his company has taken over the past 10 years. “ We GPS and photograph and text file everything we find, ” he explains, “ even if it ’ s a steel-toe shoe, airplane engine, shrimp boat, rocket, pisces trap, or tire. ”

The first time I spoke with Pritchett—in June 2018—he woke me up. A ceaseless early riser, he was returning my earphone call, at around 6:00 ante meridiem “ I don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate want to talk about the encase, ” he began, referring to the court conflict over La Trinité that was about to conclude, and then he proceeded to talk off the record for about an hour. This was my first touch that Pritchett was obsessed .

Meide, at 48, is besides exacting and driven by his own passions—particularly La Trinité. He not merely read about it in school, he recalls his father telling him that Menéndez and his men may have marched right through their backyard. Those slump ships were always at the back of his take care, and in 2000, at an archeology conference in Quebec, he turned to colleague John de Bry and said, “ We need to figure out how the heck to find those Ribault ships. ” In the late summer of 2014, he thought he might achieve his dream. After obtaining over $ 100,000 in financing from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the State of Florida, the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum, and early sources, he and a crew went looking for the ship. They spent weeks surveying a stretch of the ocean 9.3-kilometers hanker, analyzing the data, and inspecting the targets they had found. But Meide and his crew turned up only modern debris .

Meide ’ s first reaction when he heard La Trinité had likely been discovered was joy, but his second reaction was horror. “ The worst thing that could happen to a shipwreck is to be found by a care for hunter. Better that it not be found at all, ” he says, rocking back in his desk chair on the day in late August that I visit him at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum. He was worried about the worst-case scenario—Pritchett going out at night, diving to the wreck, and stealing artifacts .

Meide ’ s fear was merely amplify when, as he puts it, “ Bobby Pritchett went rogue. ” As Florida aligned itself with France, Pritchett ’ south dreams of working with the submit to excavate the ship and taking an 80 percentage cut evaporated. Meide cringed when he learned that Pritchett was alleged to have taken artifacts such as a cannonball, pick, and ballast stones from the shipwreck without license of the state of matter. Says Meide : “ He used those to go to admiralty court and try to get ownership of the wreck that way. ” Admiralty laws pertain to the capable seas, beyond state waters. The command did not succeed, and Pritchett was ordered to return the artifacts to the Florida Department of State. In Pritchett ’ randomness rendition of his permit, however, he was allowed to bring up artifacts .

Salvors like Pritchett protest that archaeologists are willing to let ships decay in the dark deeps. And what if part of the attract is a elephantine hoard of coins and gold ? Pritchett makes no bones about the fact that the potential profit of treasure hunting historic finds is a mighty lure. “ I can go back to developing homes and make three million arrant net income a year, ” he says. “ But I could go out and find one ship that ’ s worth half a billion. ”

On the web ’ s most popular treasure-hunting forum, treasurenet.com, Pritchett took the nickname of Black Duck ( an court, he says, to the nickname Black Swan, taken by the late “ godfather of care for hunt, ” Robert Marx ). There, he poured out his thoughts and gripes during the motor hotel conflict over La Trinité, and estimated the worth of his finds. On April 30, 2017, Black Duck posted, “ I believe we are looking at 50–60 milliliter for what we have found already. ” De Bry, the historian, and others vehemently disagree. “ The figures Mr. Pritchett gave are absolutely laughably inflated, ” de Bry says. “ One million dollars for a bronze cannon ? We know from auction record that exchangeable cannons have sold for $ 35,000 to $ 50,000, regardless of their origin. ”

Putting an inflate price on artifacts rather than viewing them as cultural and historic treasures that transcend any price is what kindle many archaeologists. For the archeologist, everything in a shipwreck matters, explains Delgado. “ Archaeology is more than blowing a trap in the bottom of the ocean to find a memorial and say, ‘ What is it worth ? ’ ” he says, “ Hair, framework, a fragment of a newspaper, rotter bones, cockroach shells—all things speak volumes. We don ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate want artifacts ending up on a mantel or in a private collection rather of taking us on a travel of understanding. I understand the charming of that travel. I was one of those kids who had my first dig at age 14. ”

conservation of a embark can go on for years and with a kind of dedicated care that is breathtaking. It took over a ten to treat, extract, mend, and piece together a million shards of break glassware from the celebrated “ glass wreck, ” an 11th-century Byzantine merchant ship discovered in the Serçe Limani bay off the slide of Turkey in the 1970s. The transport was excavated by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and Texas A & M University. The regenerate glass vessels from the ship now constitute the largest collection of medieval Islamic glass in being. George Bass, one of the great, early practitioners of submerged archeology, who long held a teaching and research chair in nautical archeology at Texas A & M University, coauthored two volumes on the ship ’ sulfur excavation. He explains why artifacts must be preserved : “ We excavated a seventh-century Byzantine transport found in Yassada, and we must have raised 1,000 amphoras that all looked identical, but then one of the turkish graduate students noticed graffito on the glass, and that graffiti alone enabled us to determine that the ship belonged to a church and was carrying wine over farming and sea to Byzantine troops in a certain city. ”

Bass has testified in court against treasure hunters, but says archeology is not without its own serious problems. He believes archaeologists need to do a better job themselves rather of routinely chastising gem hunters. “ Archaeology has a frightful reputation for not publishing adequate on its excavations and finds, ” he says. Collating data, exhuming and meticulously preserving and examining finds, verifying identity and origin, piecing together the larger narrative, and write and publishing a comprehensive examination newspaper or book can take decades. A bite wryly, Bass describes colleagues who never published because they waited therefore long they became ailment or died. “ We are likely never to publish the third base book on the Serçe Limani, for case, ” he says, “ since my colleague is vitamin a previous as I am. He ’ sulfur 86. ”

Who is more at fault, Bass asks, the professional archeologist who cautiously excavates a locate and never publishes on it or the treasure hunter who locates a inundate crash, salvages part, conserves part, and publishes a book on the operation ? “ I ’ meter speaking of [ salvager ] Tommy Thompson and his discovery of the SS Central America, ” he says. “ He published America ’ s Lost Treasure in 1998. ” On the other hand, Bass adds, Thompson was dishonest ; in 2000, he sold aureate recovered from the ship for $ 52-million, and in 2015, was arrested for swindling his investors out of their plowshare ; a jury awarded the investors $ 19.4-million in compensatory damages.

Read more: Maritime search and rescue – Documentary

Pritchett concedes that his recover deserves careful excavation and preservation. “ I think what I found should go in a museum, ” he says. “ But I besides think I should get paid for what I found. ”

indeed, it ’ s a bite of a mystery why nations, states, archaeologists, and care for hunters can ’ triiodothyronine work together—and why salvors aren ’ metric ton at least given a hearty finder ’ s fee before the master owner takes self-control of the vessel and its artifacts. “ That ’ s actually a effective estimate, ” says Bass, noting that the italian government gave Stefano Mariottini, a chemist from Rome, a finder ’ randomness tip for his prospect discovery of the celebrated Riace Warriors, two full-sized greek bronzes cast about 460–450 BCE. Mariottini had been aqualung diving when he found them .

***

During precolonial and colonial times, pirates, naval battles, and storms converged again and again to send whole armadas and their riches down to the shoal, coral-dotted waters off Florida ’ s boundaries .

today, the state ’ sulfur famed “ prize coast ” stretches from Roseland to Jupiter Sound. The list was inspired by 11 spanish ships, all from a single fleet, that went toss off in 1715. In 1928, a salvager named William J. Beach located Urca de Lima, part of the 1715 fleet. He raised 16 cannons and four anchors, which were put on display in the town of Fort Pierce. That was the genesis of treasure fever in the United States ; from then on, the hunt for shipwrecks was on. between 1932 and 1964, more than 50 leases were issued by Florida to salvors .

In 1961, a gem orion named Kip Wagner and his crew found and recovered about 4,000 silver coins from the treasure coast. They formed a team, called very Eight, and ultimately salvaged over $ 6-million in coins and artifacts from the 1715 spanish flit. The collection was impressive adequate to grace the January 1965 issue of National Geographic .

back then, there was no animosity between archaeologists and prize hunters, who much worked side by side. John de Bry first gear dove with Wagner in the 1960s, after a personal letter of initiation from Jacques Cousteau. Says de Bry, “ At that clock time, submerged archeology was in its infancy, and we didn ’ thyroxine think there was anything wrong with what Kip Wagner was doing. ”

In the 1960s, submerged archeology was a field therefore small that the heads of projects around the worldly concern could fit into one league room. The instruments were crude by nowadays ’ randomness standards ; Wagner detected his first ship using a 12-meter naval boat and a $ 15 metallic element detector. today, explorers use magnetometers that can detect buried metallic element, sonar devices, hydraulic dredges, and machines called prop-wash deflectors that help blast sandpaper off the ocean floor. What used to be marked with a buoy alone is now marked by GPS equally well, with far greater accuracy for return dives. commercial divers can go down an astounding 300 meters today, adjusting gases they breathe as they go, guided by modest computers they take with them .

After Wagner ’ mho achiever, Florida established laws to regulate shipwreck discoveries. For decades, treasure hunters ruled the day, sometimes taking home hundreds of millions of dollars after winning rugged motor hotel battles. Salvors found and fought for rights to the “ Jupiter shipwreck, ” discovered in 1988 south of Jupiter Inlet near Palm Beach county. They recovered over 18,000 silver coins. The world ’ s most celebrated explorer of the high seas, Mel Fisher, won rights to Spain ’ s Nuestra Señora de Atocha, which sunk near the Dry Tortugas islands, over 56 kilometers west of Key West, Florida, in 1622. The discovery was valued at closely $ 400-million. Fisher searched for that transport for 16 years, finding tattletale silver bars and cannons from the ship along the way and then discovering the embark and its motherlode of emeralds and gold in 1985. He fought Florida for eight years before he won exclusive rights in 1992 .

Fisher ’ s case was a call on indicate, however. His subject rested on the fact that the boat lie in the Straits of Florida, which in 1974 had been designated depart of the Atlantic Ocean, frankincense federal and not state waters. Federal admiralty laws trumped submit laws. Fisher proved that Spain had effectively abandoned the embark by never searching for it. His lawsuit, which went all the manner to the United States Supreme Court, set a precedent that extended salvors ’ rights to other wrecks at sea. Salvors then began to sue Florida, citing Fisher and admiralty rights .

At the lapp time, the public ’ randomness perception of shipwrecks was evolving—or, one might say, molting into something wholly new. Countries like Spain had felt the bite of losses—not only of bury riches but besides of cultural inheritance. Maritime archeology had matured, with doctoral programs at numerous universities in the United States, including Florida and Texas. According to David Concannon, the nautical lawyer who handled much of the litigation over the Titanic, the salvage of the Titanic in 1987 raised alarm bells among governments and archaeologists around the worldly concern. Archaeologists, says Concannon, recoiled at a marriage proposal by a salvager who planned to haul up the contents of the Titanic with a giant claw—a very crude technique .

In 1988, the United States enacted the Abandoned Shipwreck Act. The law dictates that rights to newly discovered ships within 22 kilometers of shore belong to the states. Beyond 22 kilometers, ships are considered lost on the high seas ( consequently potentially available to salvors ). For a shipwreck to be considered the property of a state, however, it has to be “ implant ” in the mud and sandpaper, and the entail of the term has been argued in courts .

then, in 2000, Spain won a historic case that helped formalize a new view of cultural rights to sunken ships. After a long battle, a federal appeals woo ruled that Spain had rights to two ships treasure orion Ben Benson had found off the slide of Virginia, estimated to be worth $ 500-million in coins and precious metals. Both La Galga ( which sink in 1750 ) and Juno ( which sink in 1802 ) were returned to Spain, and Spain allowed the artifacts to be exhibited in Virginia indefinitely. The United Kingdom and the United States had sided with Spain, suggesting that in the future, governments would cooperate with distant countries to the detriment of gem hunters .

The lawyer who led that case, James A. Goold of Covington & Burlington in Washington, D.C., is now a caption in nautical archeology. An archeology student in the 1970s and a diver who spends his plain meter on nautical archeology projects, he was knighted by Spain in 1999 for his efforts in this case. At the time, recalls Goold, “ Virginia was giving permission to treasure hunters to explore bury spanish navy ships. It hadn ’ triiodothyronine dawned on people that the deep-set ships of early nations are entitled to the like protection we expect for our own ships in foreign waters. ”

Another shove off to gem hunters came in 2001, when UNESCO established the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which protects all submerged traces of homo being that are more than 100 years old. Though the United States has not ratified this convention, 58 countries have signed on, including Spain, France, and Italy, and the ripple effect is felt by all .

once the Sunken Military Craft Act came into consequence in 2004, countries had two layers of U.S. legal protective covering. The military craft act has had huge repercussions for gem hunters since most european ships sent sailing on the senior high school sea centuries ago carried artillery and were effectively warships, tied when they had no intention of going to war .

When Goold quashed Odyssey Marine Exploration ’ s claim to the crash off Portugal in 2012, salvors reeled again. With that victory, which earned Goold the Commander ’ s Cross of the Order of Merit from Spain, the lawyer had basically reshaped interpretation of nautical law and how we approach treasure hound. move are the days of chumminess, when archaeologists regularly dove aboard salvors. In Concannon ’ sulfur see, “ In the early to mid-1990s, we were trying to get everybody to work together, but it was like an intifada. ” Though autonomous archaeologists will sometimes work with care for hunters, the two sides are no long allied .

For Goold, it ’ s simple : “ Ships that belong to extraneous nations remain the property of alien nations and the wishes of foreign nations are to be respected. ” not amazingly, it was Goold to whom France turned when fighting for rights to La Trinité .

***

lecture to about any nautical archeologist, and his or her contempt for prize hunters is palpable. As Paul Johnston, the curator of maritime history at the Smithsonian Institution ’ s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., points out, you can ’ metric ton break into your neighbors ’ house and steal all of their valuables .

evening the rare archeologist who sympathizes with gem hunters seems to besides sigh with exasperation : “ They ’ re like children who just got complete read Treasure Island, ” says Donald Keith, a fall through of Ships of Discovery, an educational non-profit in Santa Fe, New Mexico. But talk to any treasure hunter, and his or her simmer resentment of archaeologists is evenly intense. “ I call them ‘ burearchs, ’ ” the late Robert Marx the alleged beget of care for hunt in America, said in the precipitate of 2018 .

so far when you sit down with the men and women who pursue subaqueous exploration, they seem more alike than not. They are built of the lapp cadaver : adventurers, aqualung divers, explorers in beloved with the deep-blue sea, and to a stopping point one they are mesmerized by shipwrecks. Meide, the chief archeologist at the Saint Augustine museum, remembers the first time he felt the rib of a wrecked ship in mud. “ I thought to myself, this could have been a spanish merchant ship. It could have been a commandeer ship. From that charge I never quit. I knew this is what I want to do. ”

Those who are driven by compulsion are normally grim about finely details. Meide boasts about finding a mouse toe and spider jaw on expeditions. These sorts of discoveries evoke the daily life and diseases of long-ago seafarers. In touring the museum, he shows me how concretions—hardened mucky sludge that cover an artifact—are chipped away with bantam tools like alveolar consonant picks for weeks and months at a time .

Salvors and archaeologists are bonded by the ships, whether they like it or not. If the care for orion finds the ship, the archeologist pieces in concert its smash hull, raises coins and ingots out of the ocean, restores its cannons. And for both, it ’ s a manner of holding and possibly reshaping our view of the past. The sixteenth hundred is “ when the Old World and the New World came to meet each other and everything changed, ” Meide rhapsodizes. “ This is the pivotal hundred. ”

At 76, de Bry can ’ triiodothyronine get ships out of his blood either. He has been diving for wrecks since he was a adolescent and went scuba diving recently to investigate a 1400s shipwreck in Jamaica. He grew up in both France and the United States and made three trips to the National Library of France in 2017 to research La Trinité. “ I found a aureate mine of manuscript documents pertaining to the dispatches between the french ambassador to the spanish court and King Charles IX and Catherine de ’ Medici, ” he says. One of the letters from Queen de ’ Medici made clear that, though the french monarchy may have denied it, they knew all along they had sent “ insurgent ” Protestants to America. And that kind of discover, says de Bry, “ is treasure more authoritative than anything else you can think of. It ’ s the treasure of history. ” De Bry is likely to be hired to help analyze the artifacts and establish their place in history .

To every valet a unlike treasure, but to each an irresistible wedge that looms larger than their own lives. As Joseph Conrad wrote in Nostromo, “ There is something in a treasure that fastens upon a man ’ sulfur mind. He will pray and curse and still persevere, and will curse the day he ever listen of it, and will let his last hour come upon him unawares, still believing that he missed it alone by a infantry. ”

***

At Pritchett ’ s house in Sebastian, a stone ’ sulfur give from a museum built by Mel Fisher, the salt air is balmy, the South Florida alight weightless and brilliant. The receding ocean and its buried ships inactive beckon. Laws may have tightened and governments may have claimed his finds, but he is now refocusing on wrecks that exist beyond the achieve of such regulations. The dream will not die. “ I ’ megabyte going out to external waters future time, where local governments can ’ deoxythymidine monophosphate intervene, ” he says. “ I can tell you, there are ships in deep water not far from where I live nowadays that are worth billions of dollars. ”

interim, James Delgado ’ s firm, SEARCH, has offered to facilitate a unique external partnership between Florida and France to excavate and restore La Trinité. Ships, says Delgado, check “ the floor of all of us. ” We are, in every age and at every turn, humans caught in the fatal gears of events much larger than ourselves. “ By better understanding these colonial encounters with a new worldly concern, ” says Delgado, “ we can ready ourselves for the time when humanity sets foot on early planets. ” And so it seems appointment, about fated, that one of the greatest shipwreck finds in recent history occurred at the identical spit of land where rockets regularly blast off into space .

refer Stories from Hakai Magazine :

Read more: Australia Maritime Strategy

Recommended Videos